What is dignity?

The measure of liberty.

–Giannina Braschi

*

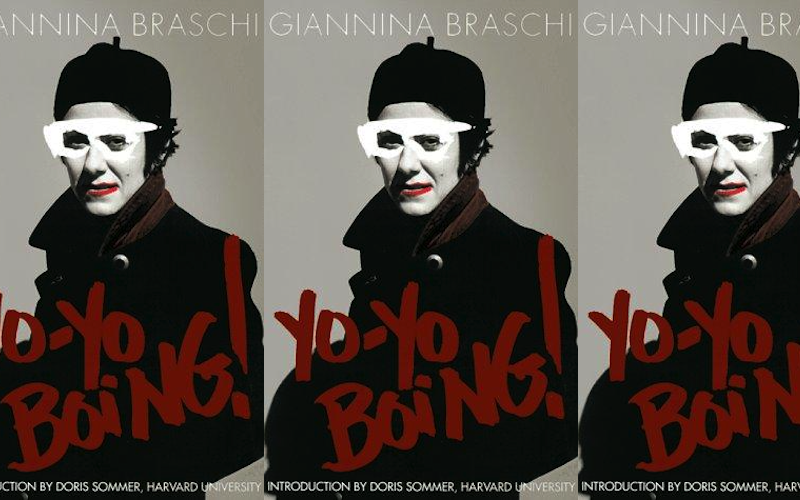

Yo-Yo Boing! has often been called a translingual text. Daringly written in Spanish, English, a combination of the two, and in Spanglish, critics have focused on the translanguaging aspects of the novel. In their introduction to Yo-Yo Boing! Doris Sommer and Alexandra Vega-Merino write: “Choose and lose is one message in the madness of Giannina Braschi’s Yo-Yo Boing! The book refuses to decide between performing in English and reveling in Spanish.”

Indeed, the book refuses to be territorialized or tied down in any manner. And that means, not just linguistically. It seeks freedom in every sense. Thus, if it begins with an eschatological scene, it is because it seeks freedom from shame and guilt, in a way that many readers find unsettling.

The work is made up of three sections: “Close-Up,” “Blow-Up,” and “Black-Out.” The second section alludes to both the technique of photographic enlargement and to Michelangelo’s Antonioni’s 1966 English language film Blow-Up, where nothing is what it seems. But then, this is no coincidence, for nothing in Braschi’s work is there without a reason, even if it seems otherwise.

The first section, written in Spanish begins with the becoming-animal of an unnamed character who has a trump like an elephant and crawls on all fours like a little girl. The character defecates, scratches herself, removes pieces of skin from her body, and plays with herself. She attempts to bring order to the chaos by applying cosmetics: blush on her cheeks, sherry-colored lipstick on her lips (“wet and ready to kiss a cherry”) and thus she becomes a circus clown. Where is reality? she asks the magic mirror on the wall.

But the fecal chaos of reality it turns out is what make-up is there to cover: odors, pimples, decay, and the death from which we turn away. And yet that is precisely what Braschi has focused on in Close-Up. Not to shock, but rather to liberate. In fact, for Braschi the mouth and the anus are openings that give expression to all that is inside of us, good and foul. The painted lips produce the sound of O, the sound of openness. “O is the motor of O,” writes Braschi, “of the exclamation: ¡OH! ¡OH!” We are free to open or close our mouth as we see fit and take equal pleasure in both.

Ábrela tú.

¿Por qué yo? Tú tienes las keys. Yo te las entregué a ti. Además, I left mine adentro.

¿Por qué las dejaste adentro?

Porque I knew you had yours.

¿Por qué dependes de mí?

Just open it, and make it fast.

So begins “Blow-Up,” the second section of Yo-Yo Boing!: with a code-switching dialogue about having the keys to open the house door. And yes, it has something to do with language, but only insofar as language is a key to opening other more important doors. There is no Derridean linguistic self-referentiality in Yo-Yo Boing! This is not a text about texts, but rather a text about worlds.

When someone tells the character Giannina that she is limiting her audience by writing in English and Spanish at the same time because languages are culturally specific, Giannina retorts that if she respected languages, she would not write at all.

When someone tells the character Giannina that she is limiting her audience by writing in English and Spanish at the same time because languages are culturally specific, Giannina retorts that if she respected languages, she would not write at all. She says: “I feel like Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio, and I even feel like Garcilaso forging a new language. I welcome the new century, the century of the new American language, and wave farewell to all the separatist rhetoric and atavisms.“

In Whitmanesque fashion, her fearlessness is based in the concept that: “My confusion is my statement of clarity. I live with plenty of identities within myself.” In short, her relation to language is primarily existential rather than linguistic or syntactical, and if there is an allusion here is to the freedom of embracing what Sommer and Vega-Merino call a logic of the Either And.

Here again, I am persuaded to return to Antonioni’s Blow-Up, a film made by an Italian director with English actors, based on a Spanish language text (Julio Cortázar’s short story, “Las babas de diablo”). For Yo-Yo Boing! is not very different than Blow-Up. In our case, it is a book written by a Puerto Rican writer of Italian descent, in English and Spanish, that requires a close reading (similarly to Blow-Up) to see what lies behind the (writerly) text. In seeing and reading beyond the given lies true freedom.

Such liberation, however, requires individual initiative, and a Nietzschean rejection of accepted mores and human relationships. “Why do you depend on me?” asks a character and the other responds: “Just open it, and make it fast.” But it is the question that is important, for the interlocutor’s answer above is only one of expediency, for only through independence can nations and individuals be free. One cannot embark on new voyages without breaking the ties that bind, be it those of language, morals, or ways of life.

And this is clearly demonstrated in Black-Out, the last section of Yo-Yo Boing! in a text entitled “Perro Realengo” or “Stray Dog.” Here Braschi writes:

When I speak I’m leaving what I’m saying on this ship…and who knows where we’re going but we’re going somewhere—and we’ve lost sight of what we left behind—we gave so much importance to what we’ve left behind—and look how small it’s becoming now that we’ve left it behind…but as long as there are no limits—as long as we’re going even if we don’t know where we’re going—we’re always going where we go and leave everyone and no one behind—and no one is so important that we can’t leave on this voyage that takes us—good bye—towards unsuspected frontiers, where the frontier is the only suspicion that suspects….I always look beyond the horizon of the sea, where I want to arrive, where no one has ever arrived, al di là.

Leaving old loves behind us is hard, but for Giannina it is the only way to move forward. In a brief dialogue on Ingrid Bergman’s performance of Jean Cocteau’s monologue The Human Voice—of a woman talking on the telephone with the lover who has left her for a younger woman—two characters (one of them presumably Giannina) discuss the plight of the desperate, suffering woman. Giannina imagines the lover and his new girlfriend listening with “deep pleasure” to the effect he has had on the suicidal ex. It is the guilt-free response of the stoic who knows that there is no going back—that “[o]ne can’t step into the same river twice. There are new waters.”

In this very classical sense, Yo-Yo Boing! is a veritable comedy for our times. Despite its darkness, its eschatology, like Dante’s Commedia, it ends well: with the hope of freedom.

And those who are afraid to embark on new journeys of discovery and creation are destined to end up like sardines in a can. “If you allow yourself to be packaged in a sardine can, it is because you are a sardine,” writes Braschi. The Nietzschean tone of the above passages is undeniable. And aptly so, Yo-Yo Boing! ends with a dialogue between Giannina, Hamlet, Zarathustra (just as in her 2011 novel, United States of Banana).

In the short play, Giannina carries the body of the twentieth century, which she seeks to bury. When Zarathustra asks her where she is going to bury it, she answers “[i]n the mausoleum of liberty,” and when Hamlet asks her who gave her permission for the burial, Giannina answers “God who is dead!”

Not lost to Giannina, and of course, to Giannina Braschi, is the fact that for Nietzsche the death of God represented the opportunity to create new values out of ashes of the new acquired freedom. And so, the celebration begins with the dynamite that announces: “¡Fuego! Aire. Alegria or Fire! Air. Happiness.” And all kinds of free flows, from water to urine.

In this very classical sense, Yo-Yo Boing! is a veritable comedy for our times. Despite its darkness, its eschatology, like Dante’s Commedia, it ends well: with the hope of freedom. It also ends with an eruption of good humor, and so it is no wonder that the title itself refers, among other things, to the Puerto Rican comedian, Luis Antonio Rivera, a.k.a Yoyo Boing.