Welcome to Lit Century: 100 Years, 100 Books. Combining literary analysis with an in-depth look at historical context, hosts Sandra Newman and Catherine Nichols choose one book for each year of the 20th century, and—along with special guests—will take a deep dive into a hundred years of literature.

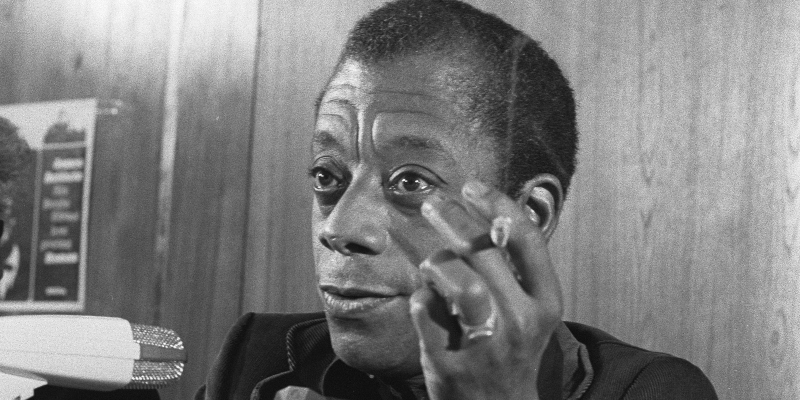

Isaac Butler joins hosts Sandra Newman and Catherine Nichols to discuss James Baldwin’s play Blues for Mister Charlie (1964), written to address the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till. In this episode we discuss the troubled performance history of the play. We also talk about how Baldwin approached the writing of a play (a genre he generally disliked), and his place in the history of African American writers grappling with the problem of writing political literature that spoke to both white and Black audiences.

From the episode:

Isaac Butler: I think the way Baldwin is trying to solve some of these problems has to do with metatheatricality and self-conscious performance, and that to me is what feels so fresh about the play. The weird thing about Richard is that the various versions of him that we see don’t really cohere. He is—and I’ll assume intentionally—a pretty different person depending which audience he’s performing in front of, which I think is how he seems to see each of those scenes that he’s in, is as a kind of performance. Whether it’s with his father or with his friends with the photos of the white women, or once he’s in the store and he’s kind of performing to demonstrate Lyle’s weakness for his friend. And he’s also a performer by trade—he’s a guitarist. He is actually a performer; that’s his job. And so I think there’s a way in which he’s always performing that I find really fascinating.

And then there’s all these other layers of performance in the play as well. The play begins with this incredibly provocative scene, which is the scene of Richard’s death, although you don’t actually see the death at that moment. You hear a gunshot, and then Lyle says this thing about how Black people should die facedown in the reeds, although he uses the n-word. And then it immediately jump-cuts to the reverend telling a performer—and you’re not really sure who he’s talking to yet—that he hasn’t said the n-word convincingly enough. He hasn’t said it the way white people say it.

And it’s important that that first moment with Lyle is kind of in darkness. You don’t really see what Lyle looks like there, so you’re really for a split second not sure who the reverend is talking to. Of course, what he’s actually doing is running a nonviolent resistant workshop in which they’re pretending to be white people hurling racist harassment at protesters, to role play how to stay calm in those situations. So it begins with this weird enactment of a thing and then a rehearsal of this racism. And then there’s these constant moments of performance throughout, which again culminate in that trial scene, which is very strange, in which there is really no hope that any truth can come out in that world, in part because everyone is delivering some kind of performance for an audience that is actually reacting and shouting at them while they’re giving their testimony, and in which almost every single person who testifies lies about something, if I remember correctly, including the African American characters. So there’s this weird way in which he’s trying to use performance to solve some of these problems.

I’m not sure how successful it is, but I was thinking about this because Shonni Enelow, who wrote this great book called Method Acting and Its Discontents, wrote about this play, and what she mentions is that this play is actually the hinge in the politics of his body of work—that his work before it is more liberal and his work after it is increasingly radical and separatist, and that this to her is the play where he’s trying to figure out some way to knit those together. And so, she says something like both Blues for Mister Charlie and Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone illustrate Baldwin’s struggle to articulate a third way between the universalism that method acting modeled and that had characterized Baldwin’s own voice as a young writer, and the separatism he would later embrace.

***

To listen to the rest of the episode, subscribe and listen on iTunes, Stitcher, or wherever else you find your favorite podcasts.

Isaac Butler is the author (with Dan Kois) of The World Only Spins Forward: The Ascent of Angels In America, and also of the forthcoming The Method. He is also a theater director, most recently of The Trump Card, a meditation on the peculiar rise of Donald Trump; he also wrote and directed Real Enemies, a collaboration with the composer Darcy James Argue and the video artist Peter Nigrini, which was named one of the top ten live events of 2015 by the New York Times. He is the co-host of Slate’s Working podcast.

Sandra Newman is the author of the novels The Only Good Thing Anyone Has Ever Done, shortlisted for the Guardian First Book Award, Cake, and The Country of Ice Cream Star, longlisted for the Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction and named one of the best books of the year by the Washington Post and NPR. She is the author of the memoir Changeling as well as several other nonfiction books. Her work has appeared in Harper’s and Granta, among other publications. She lives in New York City.

Catherine Nichols is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in Jezebel and The Seattle Review, among others. She lives in Boston.