I was taking an online graphic narrative class and one of the other students, looking at the first page of a piece about falling from a tree and breaking my back when I was ten, said, “Don’t draw an apple, then write Apple.”

Article continues after advertisement

I’m a writer. I’ve taught creative writing for 35 years. But this was my first comics class. The firmness with which the woman spoke made her advice sound like the comics equivalent of the standard fiction writing advice, “Show, don’t tell.”

“In graphic narratives,” the teacher explained, “ideally the words and image should be doing different things. You don’t want to just draw an illustration of the words. Or use words to label the image. You don’t want a page or panel to be just Apple x Two.”

She was looking at the first page of my piece, a pencil drawing of ten-year-old me, mid-air—looking, I realize suddenly, a bit too much like the Little Prince—falling from a very tall tree. The text, hand-lettered in the open space representing the 30 feet from the tree’s branches to the ground, read: “When I was ten, I fell from a tree.” Falling x Two. “Though, of course, there are times when it’s exactly what you need.” She did not say if that was the case with my page but looking at it, I was pretty sure it was not.

After the class, I tried to Google, “Don’t draw apple then write apple,” but all I got was page after page of advice about Apple products.

I’d only started drawing five months earlier, at the beginning of the pandemic while locked down in a rented apartment in Montevideo, Uruguay. Since then, I’d been drawing what I called a “sketch of the day” and posting it on social media—my version of sourdough. Like bread baking, I’d started drawing to do with my hands. Something that was not on my computer. I sat all day, every day, laptop in lap, writing or reading student work. But I drew standing up, at an easel, on big sheets of paper.

I’d started with colored pencils, but lately had moved on to pastels, drawing a series of women with red hair, running through the reds in each box before any other color. And also groups of women, mostly looking sideways at each other. My rules were: A. I had to finish a drawing every day. B. Once I started, no tearing it up and throwing it away. C. I had to post it (to keep me honest about my progress or lack of it).

But I did not consider these drawings pieces of a narrative. They were the wordless part of my day. I looked back at the drawing of me falling from the tree. I had drawn those pages for the class because I was thinking of redoing my published memoir (or what I thought of it now as my ALL WORDS memoir) Space, about growing up in Florida during the moon race. I’d gotten as far as doing penciled pages (or thumbnails as I learned in the class to call them) of the first three chapters, trying to cut down on the sheer quantity of words, to draw only the scenes I decided were important. I looked at them now and saw a whole lot of Apple.

But I was not sure what to do about it. What I did do was keep going as I had been, stubborn, head down, drawing art and making comics on completely different tracks. I drew my sketch of the day, working more and more in bright, slightly surreal pastels. But I kept thinking the sensible comics project for me was turning Space into a graphic memoir. In tidy ink, maybe with neat touches of watercolor. I realized, though, except for having taught Maus one semester, I’d read very few graphic books. I’d not been a comic book kid either, having gone the route of all words.

Now, I wrote down names of authors people mentioned, asked them for titles. One of my favorites, and nearly everyone else’s as well, was Allison Bechdel’s Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. I imagined my graphic memoir working the same way, clean, neat drawings in panels with a reasonable amount of text narration and dialogue bubbles. I studied each panel, what the text told the reader, what information, and especially emotion, was only apparent in the drawing. I drew more thumbnails. They were not better. I would say something. I would draw what I just said. Apple, apple, and more apple.

In my word life, the minute I told myself exactly what I was going to write and exactly how I was going to write it, the story would go dead on the page. I could have an idea, a sketch of a plan, but if everything was already decided, done, the creative side of my brain would just shrug, and say, Then why put in all the work? And take a long, unhelpful nap. The fun was discovering the story on the page as I went along.

Then I was lucky enough to take a semester comics class with Lynda Barry. Her homework and prompts involved both words and art, though I think she would say there is no difference between the two. We wrote, then we drew what we wrote. We drew, then we wrote about it. Her instructions were specific, the exercises often timed so we couldn’t overthink what we were doing. She knocked me out of my logic box.

One of her prompts (which she credits to writer Dan Chaon, another example of how she erases the boundaries between the art and word worlds) was to write an eight-page character zine all in one sitting, writing about someone you knew when you were young but not seen or thought about in a while. We drew and wrote each page in four minutes in response to prompts like “Write some dialogue. Something someone said about this person to you or someone else.” And then above that, on the same page, “Draw your character eating their typical lunch.”

I left logic and planning behind and just kept drawing and writing and then, suddenly but not suddenly, I had finished a graphic memoir.

The very antidote to Appleness. The relation between the text dialogue and the drawing was organic, implied. I finished a zine called “Odile,” about the woman who took care of me when I was a baby in France and the times I had seen her later in life. It was nothing I had thought about before, written about before, drawn before. I felt wonderful working on it, scared (only four minutes!) but so very alive. Then in my final project for her, I included two chapters from my graphic version of Space, freshly drawn, inked and water colored. “Hmm,” she said, looking them over, “you don’t need to always draw the same thing you just told us.”

Damn those apples.

But while I was in Lynda’s class, when I posted a sketch of the day, I started adding a bit of text—like narrative titles. “She wouldn’t listen” or “She dreamed she was inside a clock.” Words joining my art. Then, one day, when I finished a lyric essay, “Broken,” about the sheer number of the times I’ve fallen and broken a bone or bones, I dropped some drawings I’d already done as daily sketches in between sections. “We were happy. All of us,” was paired with a drawing that contradicted the text, three women, one jumping in the air, but two sitting, their heads in their hands.

But another was more connected, closer to an illustration. “I went to the party. I am one of these women.” the text read. The drawing was five women, one facing the viewer, three others seen from behind. The last woman looking across the page at the first. Five women at a party. Was that Apple x Two? Or was there something more there? “I am one of them.” Which one? How could the reader really know? Did that mystery make the drawing count as that elusive something more? Maybe, but these were just essays with art. Not comics. Not the graphic memoir I had imagined drawing.

I signed up for an online graphic narratives class with the British artist Sarah Lightman through Royal Drawing School in London. Her idea of what could be a graphic narrative was more open, a broader view of words + art. Her examples were not always caged inside panels like Zoom squares. She showed us art by well-known contemporary artists who used words on their canvases. The large obsessive, autobiographical paintings with text of the Jewish artist Charlotte Soloman, who died in the Holocaust.

I read Lightman’s own The Book of Sarah, about her life and family. The class let me give myself permission to do more of what I was calling illustrated essays. I drew one called “The Fox Sister” that combined a real fox nursing her kits in the yard next to mine, the 19th century spiritualists the Fox Sisters, the Korean folk tale the Fox Sister, and my own mother. It was full of women with red hair, women who might or might not also be foxes.

Then, one day, like a brick wall tumbling down, the words and art collapsed into each other, onto each other. The text appeared on the drawing. Like a comic. But not like any of the comics I had been trying to make myself draw. No panels. No bubbles of dialogue. They were something more, well, hybrid. I drew and wrote in a frenzy. My grandmother as the Wolf in Little Red Riding Hood. My father as Napoleon. My mother on a frozen lake, on a ship in danger of sinking, in a thorn pricked orange grove. Autobiographical but surreal.

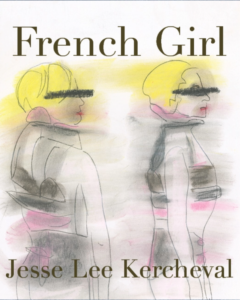

Looking back at my past through a lens of fairy tales and imagined history. I left logic and planning behind and just kept drawing and writing and then, suddenly but not suddenly, I had finished a graphic memoir, French Girl Something that was not Space. Something that was not full of Apple x Two. 250 pages of it. All the while I thought I was lost in that dark, tangled apple orchard, I was finding my way to something new.

______________________________________

French Girl by Jesse Lee Kercheval is available now via Fieldmouse Press.