The 1970s closed with one of comedy’s great controversies.

Monty Python’s Life of Brian was an outrageous parody of biblical times. Its wild sight gags, absurd humor, convincing set design, and social commentary delighted Monty Python fans. However, politicians connected to the evangelical movement suggested that the members of Monty Python—John Cleese, Eric Idle, Graham Chapman, Terry Jones,Terry Gilliam, and Michael Palin—be tried for blasphemy.

The idea of a biblical parody made film producers nervous. “Originally, we had the money from EMI for this film,” recalled Terry Gilliam. “It was, I believe, the Thursday before the crew was leaving [to start filming], we got the news that EMI had pulled out because apparently [film executive] Lord Bernie Delfont had finally got around to reading the script, decided it was blasphemous, and didn’t want his company to be involved in it … Everything was canceled.”

“Delfont had been approached by certain elements and leaned on, and warned, that this would be trouble, this film,” recalled Eric Idle. “He didn’t want to cause offense. Y’know, you can understand it from his point of view, but from our point of view, we had already spent about eighty thousand quid on locations and getting things going.”

The film was saved by one of Eric Idle’s friends—George Harrison. The former Beatle put up four million dollars of his own money and rescued the production.

Investors were right to be cautious. As soon as it was released, Life of Brian was besieged by religious fundamentalists. Orthodox rabbis were the first to protest, objecting to a prayer shawl worn by John Cleese at the start of the film.

“It was the first scene to raise any protests,” said Terry Jones. “We always thought we were going to get protests from Christians, but in fact the first lot of protests we got [were] from the … Rabbinical Association of New York.”

Politicians connected to the evangelical movement suggested that the members of Monty Python be tried for blasphemy.

Idle said, “The rabbis went away as quickly as they had appeared and were replaced by angry Christians, who picketed the Burbank Studios in LA, claiming that Warner Bros. were the agents of the devil.”

Blasphemy charges were seldom successful in the modern age. Organized evangelical groups figured they’d have better success if they attacked the film on grounds of obscenity. A half-second glimpse of Graham Chapman’s penis led to a court order which suppressed Life of Brian in the state of Georgia due to “lewd exhibition of genitals.”

The movie was banned in Shreveport, Alabama, outlawed in Alexandria, Louisiana, and harassed in South Carolina.

“The film held up to deliberate ridicule my faith in Jesus Christ and made fun of His suffering,” said Presbyterian minister William Solomon. “It was cruel and sarcastic, but it was not art.” Solomon contacted South Carolina senator Strom Thurmond for help. Thurmond insisted the film distributor withdraw the film, telling them, “My folks take their religion very seriously.” The distributor replied, “We take our freedoms very seriously, too.”

The film was saved by one of Eric Idle’s friends—George Harrison.

At a theater in Columbia, South Carolina, protesters distributed leaflets about eternal damnation. Monty Python fans held a counterprotest and carried signs that said, “Strom Doesn’t Pay for My Movie Ticket” and “Resurrect Brian, Crucify Censors.”

Senator Thurmond inadvertently helped as controversy drove ticket sales. “There was no need for us to fly to the States and do publicity,” said Eric Idle. “So, while the movie was being pulled from cinemas across America, people would simply drive across state lines. This pattern repeated itself everywhere.”

On an episode of Friday Night, Saturday Morning on BBC2, Michael Palin and John Cleese debated a priest and the recently born-again writer Malcolm Muggeridge about the film’s merits.

“I would simply point out to you,” Muggeridge told them, “that if you care about what constitutes what we call Western Civilization—which now is probably coming to an end—and you were to consider the role that’s been played in that by this … piece of buffoonery, you would have a certain humility … This is such a tenth-rate film … and the lampooning of His death, which is the most disgraceful part of the whole thing … and all you’ve done is to make a lot of people on a cross singing a music hall song. I mean, it is so disgusting.”

Ironically, Malcolm Muggeridge once contributed an essay to Esquire complaining that people were so sensitive you couldn’t joke about anything anymore. “The area of life in which ridicule is permissible is steadily shrinking, and a dangerous tendency is becoming manifest to take ourselves with undue seriousness,” wrote Muggeridge in 1958. “This decay of humor on both sides of the Atlantic doubtless derives, partly at any rate, from the growing sense of insecurity which haunts the lives of so many today. When institutions and authorities feel themselves to be secure, ridicule and satire are unobjectionable.”

The movie was banned in Shreveport, Alabama, outlawed in Alexandria, Louisiana, and harassed in South Carolina.

Life of Brian was banned in Ireland. It was banned in Norway. And it was suppressed throughout the United Kingdom. Screenings were forbidden in Birkenhead, Brynmawr, Cornwall, East Devon, Haverfordwest, Harrogate, Pontypridd, Swansea, and Whitehaven. The town of Watford allowed it, but only after changing the film’s rating to an X. And an advertising campaign in Sweden mocked their neighbor: “Come see Life of Brian! A film so funny they banned it in Norway!”

The controversy faded after a year. By the 1980s, the film was syndicated on television and aired on weekend afternoons in several markets—and nobody seemed to care.

“It showed you how much absurd posturing goes on,” said John Cleese. “Because people protest and protest and protest and say this is really, really bad. And then two years later the film is shown again and nobody turns out at all. It’s about posturing. It’s about people feeling they’re doing God a favor by going out to protest.”

“We were pilloried by religious groups on all sides from Jews to Catholics to Protestants,” said Terry Gilliam. “To me, what’s important is that we managed to offend a lot of people. But as you notice we were very cautious about offending any Muslims. We would say nothing negative about a Muslim, ’cause we’d get a fatwa after us. But your Jews, your Christians, they’re easy to push around.”

“I was very surprised by the degree to which some people protested,” said Cleese, years later. “I did not have an enormous amount of respect for the most vocal people who went out and demonstrated. I had a lot of respect for people who came up to me and told me quietly and rationally what bothered them in the film … I was also surprised by how many people wrote to me and said, ‘I am a Christian and I don’t know what this fuss is about. It seemed to me perfectly clear that you were making fun of the way that some people pretend they’re Christians—when they’re not actually following Christ’s teachings.’”

Eric Idle said it eventually all came full circle. “One nice footnote to the Brian controversy, in our movie, Sue Jones-Davies, a Welsh actress, played Brian’s reactionary girlfriend Judith … When the movie was first released in her hometown of Aberystwyth in North Wales, the local council banned the film from public screening. Thirty years later she became the mayor of Aberystwyth and overthrew the ban.”

___________________________

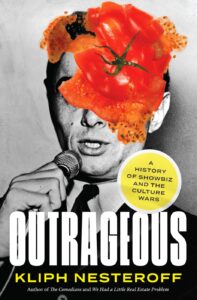

Excerpted from Outrageous: A History of Showbiz and the Culture Wars. Copyright © 2023 by Kliph Nesteroff. Used with permission of the publisher, Abrams Press. All rights reserved.