The story goes something like this.

William Friedkin needed to find the right little girl for his film. She had to be strong and stable, good humored and intelligent, someone who could say lines like “Let Jesus fuck you” and not be left irreparably damaged. Friedkin didn’t want any responsibility for setting some innocent little girl off on the wrong path for life. The filmmaker was entering uncharted cinematic territory, and he must have paused, or at least we hope, to consider an important question: What will playing the devil incarnate do to a young child? As he started his search, Friedkin knew at least this much: the little girl had to be a good actress, and of course, she had to be pretty.

In the book version of The Exorcist, Regan has freckles, red hair, and braces, just like I did when I turned 12. Friedkin would take certain artistic liberties when casting his Regan, preferring tall, snub-nosed brunettes. He spent months searching, flipping through stack after stack of sunny young actresses, all white, shiny, and smiling. He’d bring the ones he liked into his office for an audition, but none of them were quite right. Some seemed too immature to handle the intensity of the role; others were promising, but their parents balked at the image of their sweet daughter transforming into a monster. Even the most fame-hungry stage parent thought such a role would hurt, not elevate, their child’s burgeoning career.

Mike Nichols had passed on the project because he didn’t want the success of the film to depend on the performance of an untrained child. Friedkin was starting to think Nichols was right. But then round-faced Linda Blair walked into his office. Friedkin was a big name around Hollywood in those days, and working with an Academy Award–winning director could open serious doors for an aspiring actress, even one who up to that point had only landed a few child modeling gigs and a small role in the short-lived soap opera Hidden Faces. Linda Blair, born just a few months before my mother in 1959, was a sweet-natured, horse-loving child actress living in Connecticut with dreams of staring in movies about princesses, about little girls and their dogs. If she hadn’t made it as an actress, Blair would have been perfectly content growing up to be a jockey or a veterinarian. Getting cast by someone as illustrious as William Friedkin, with his tinted aviator glasses and gargantuan ego, was certainly a long shot, but Linda’s mother took her daughter to the audition anyway. The Blair’s old address in St. Louis must have seemed like an omen: 123 Hollywood Lane. Friedkin had auditioned countless girls and liked none of them, so maybe, just maybe, Linda had a chance.

When Linda and her mother arrived at Friedkin’s Manhattan office, William asked a few basic questions and then went over the script, discussing in detail some of the things Linda would be required to do if she were cast. When they approached the scene where Regan masturbates with the crucifix, William paused and prepared to ask what he had asked stacks of other girls before her. He took a deep breath.

“Linda,” he said. “Do you understand what Regan is doing here?”

“Yeah,” Linda responded eagerly, as if she were in class and knew she had the answer the teacher wanted. “She’s masturbating.”

William nodded.

“And do you know what masturbating is, Linda?” “It’s like jerking off,” Linda replied.

“And have you ever masturbated before?” William asked, shooting Linda’s mother a tentative, apologetic glance.

“Sure, of course I have,” Linda said. “Hasn’t everyone?”

With that, Friedkin smiled and leaned back in his chair. His search, at last, could end.

She had to be strong and stable, good humored and intelligent, someone who could say lines like “Let Jesus fuck you” and not be left irreparably damaged.

Pauline Kael mentioned this story in her 1974 review of The Exorcist. She describes Linda Blair as a “sparkling, snub-nosed, happy-looking little girl, who matches up perfectly with Ellen Burstyn.” Kael adds, “I wonder about those four hundred and ninety-nine mothers of the rejected little girls. . . . They must have read the novel; they must have known what they were having their beautiful little daughters tested for. When they see The Exorcist and watch Linda Blair urinating on the fancy carpet and screaming and jabbing at herself with the crucifix, are they envious? Do they feel, ‘That might have been my little Susie—famous forever?’”

*

In the notorious scene, vinyl records swirl through the room in a manic cyclone. Curtains slap wildly against the window-pane. The girl’s mother rushes in and finds her daughter sitting upright in bed on her knees, stabbing herself repeatedly with a crucifix until she spurts bright red blood. It makes a horrible sound, like a dull knife goring through ripe fruit. You can just imagine the foley artists in postproduction going at a grapefruit like mad. The motion, and the slight thrust of the little girl’s hips as she does it, is violent, greedy, wrong. As she stabs herself, the little girl growls “Let Jesus fuck you” again and again, her eyes frantic and wide.

Chris rushes over to Regan and tries to grab the crucifix from her hand. Instead, the girl yanks her mother’s head into her bloody crotch and holds it there. “Eat me! Eat me!” she barks. When Chris surfaces, her frightened face is stained with her daughter’s blood. Regan then punches her mother with a strength well beyond that of a 12-year-old girl. Chris’s body hits the back wall with a loud thud. A dresser barrels inexplicably toward where she cowers in the corner, presumably propelled by the demonic force thrashing inside Regan. Chris gasps and dashes away just in time. For all the cultural fervor around the crucifix-masturbation scene, few people ever bother to point out that Regan also comes frighteningly close to committing matricide.

Before she leaves the room, Chris takes one last look and sees her daughter’s head spin slowly around, a full 360 degrees. The camera zooms up on the girl’s face—teeth jagged, skin pale, eyes not quite human—as she growls, “Do you know what she did? Your cunting daughter?”

William Peter Blatty considered this scene a necessary solution to a nagging plot problem: What is so horrible that it would drive an atheist to a priest? He had already done so much work establishing Chris as a logical and devoted nonbeliever that any sudden and dramatic conversion would seem entirely out of character. To make the plot progress in a logical way, Blatty needed a moment so appalling and unexpected that Chris would finally accept that something supernatural was at work. It had to shock her conscience into belief. And what is worse to imagine, in a country simultaneously puritanical and perverse, than a violently masturbating little girl?

The scene would not only solve a thorny narrative issue, it would also prove commercially viable: The crucifix-masturbation scene was an undeniable audience draw. Many people paid to see The Exorcist solely because, thanks to the dissoluion of the Motion Picture Production Code five years before, they could now watch something so graphic and shocking play out on an American screen.

A little girl, they must have whispered, masturbating with a crucifix.

*

Despite Friedkin’s colorful story about Linda Blair’s audition for The Exorcist, Blair has maintained that she did not know what masturbation was when she was cast, nor did she understand what was happening in this scene when it was filmed. In the documentary The Fear of God: 25 Years of The Exorcist, Blair says, “A child does not know what those words mean. … A child does not understand what masturbation is.” Blair describes shooting the scene as “very mechanical,” with Friedkin carefully directing her every move.

To counter the media storm claiming that Blair was psychologically disturbed by the intensity of her role, Friedkin and Blatty have always maintained that production was a fun and lighthearted affair for their young star. You can find photographs and footage online of Linda Blair laughing and smiling on the set, drinking milkshakes in her hospital gown and goofing off for the camera while bound to the bed. Friedkin even says he became a “surrogate father” to Blair, tickling her playfully before shooting particularly gruesome scenes and taking the time to explain things like lens types and lighting to her during moments of downtime. By most accounts, Blair was an incredibly bright and well-adjusted young girl, a “jewel,” according to Blatty, who never once complained about anything.

Blair, once again, counters this narrative. “I don’t think anyone has ever understood how hard it was on my end,” she has said of filming The Exorcist. From Blair’s perspective, it wasn’t that she never complained. It was that she did complain, but no one heard or understood.

What is worse to imagine, in a country simultaneously puritanical and perverse, than a violently masturbating little girl?

Most famously, Blair was injured while filming a scene where her out-of-control body flails and thrashes on the bed, jerking up and down like a jackknife. To shoot the scene, Marcel Vercoutere, the notorious French special effects coordinator, strapped Blair into a remote-controlled harness that he operated with relish from the sidelines. In 1983 Vercoutere told Fangoria magazine,

I was the devil! … I had her strapped in there, and I was throwing her back and forth. When does the acting start and the realism begin? To say she is being possessed and thrown and picked up, jiggled and bumped, and to get that horror and not going too far, not to hurt her, or bruise her. Up to a certain point, it’s for fun, then it starts to get more violent. And she starts to say, “Okay I’ve had enough.” Now that’s when you start!

Blair had no control over when the contraption stopped or started, or how fast her own body was made to move. Not surprisingly, she ended up injuring her back when a piece of the equipment came loose while filming.

“I’m supposed to be yelling, ‘Make it stop!’” Blair told Mark Kermode. “And that’s what I was yelling. But nobody realized I meant it.”

The crew brought in doctors and a masseuse to treat her injury.

“A child’s body will heal,” Blair said. “And I was very strong. But it was tough work.”

To produce the vomit that Regan must spew over the priests, master makeup artist Dick Smith devised a plastic mouth harness, not unlike a horse’s bit, which would pump pea soup into Blair’s mouth through a nozzle. Blair describes spending hours on set with her mouth wide open.

Though Blair’s body double, Eileen Dietz, has since claimed that she was actually the one forced to wear the bit, Blair nonetheless endured a string of equal discomforts at the hands of Smith and the production crew. The contacts she wore to turn her eyeballs white reportedly stung, and the glue used to secure prosthetic scars to her face burned and irritated her skin. For the possession scenes, when Friedkin kept the set at frigid temperatures, the crew wore old ski suits to keep warm. Blair, on the other hand, spent most of the day in a thin nightgown and long underwear, shivering and blue lipped, even as snow reportedly fell around her.

Actresses often describe the hours they spend in the makeup chair as a kind of excruciating and mind-numbing endurance test. Blair is no different, except that she did her time staring not only at her own transformation but also at the reflection of the grotesque Regan dummy used in the scene where her head does a 360, which Dick Smith insisted on keeping in her dressing room.

Of being forced to stare at her shadow-demon self for hours on end, Blair has said, “I didn’t enjoy the experience of being in its presence.”

*

Though Friedkin has stated over the years that Blair had no stand-in or substitute, it has since been officially acknowledged that snippets of the more graphic scenes were actually performed by a body double, Eileen Dietz. In the case of the crucifix masturbation, it is Dietz’s hands we see driving the blood-splattered crucifix into her crotch, not Blair’s. Dietz appears on and off again throughout the rest of the film, for a total of 28 and a half seconds. Warner Bros. was forced to do the calculation when Dietz, along with Mercedes McCambridge, sued for credit. Unlike McCambridge, who simply wanted credit for voicing Pazuzu, Dietz falsely claimed to have performed all of the possession sequences in the film.

The ensuing public battle between Dietz and Blair was nicknamed “the Great Pea Soup War.”

Though the knowledge that young Blair was not in fact miming masturbation did little to stem rumors that she was psychologically deranged by the role (the world, it seemed, really did want her to be broken by it), some believe it did hurt her chances of winning Best Supporting Actress at the 1974 Academy Awards. The Oscar instead went to another child actress, the plucky 11-year-old Tatum O’Neal, who starred alongside her real-life father in Peter Bogdanovich’s black-and-white period piece, Paper Moon.

Blair didn’t win the Academy Award, but she did announce the award for Best Short Subject alongside actor Billy Dee Williams, who had recently won praise for his performance in the Billie Holiday biopic, Lady Sings the Blues. On stage, Williams asked Blair if she’d gotten around to watching her much-talked-about performance in The Exorcist. Blair cocked her head and smiled, preparing for one of those inescapable Oscars one-liners.

“Well,” she replied sagely, “I don’t like standing in lines.”

Though O’Neal made history that year as the youngest person ever to win an Academy Award, perhaps Blair deserves credit for a different Hollywood first. Hedy Lamarr may have performed the first on-screen orgasm in the film Ekstase, but Linda Blair will forever be marked by cinematic masturbation’s opening salvo, the sound of something sacred and sharp tearing through young female flesh.

__________________________

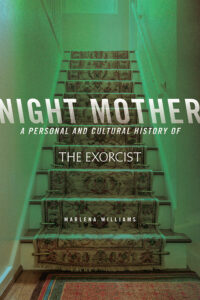

Adapted from Night Mother: A Personal and Cultural History of The Exorcist by Marlena Williams, published by permission of Mad Creek Books.