In the fall of 2012, I said goodbye to my thirteen-year-old cat, Snowflake. The grief was breathtaking, in a literal sense: it took the wind out of me. I had tried to brace myself, but I’ve since learned that it’s impossible to prepare. In the days and weeks that followed, I couldn’t focus and barely ate. I missed her reassuring presence beside me when I fell asleep at night and dreaded waking up to the awful reality that she was no longer here. Snowflake’s absence had created, in Steinbeck’s words, a “jagged hole” in my life.

Disoriented and overwhelmed, I did what I often do in crisis: I searched for a book that could guide me through that painful time. I knew what I wanted to read: memories, advice, and encouragement from others who had been down the same path—small portions of literary nourishment that would provide solace and perspective without requiring sustained concentration.

I wanted to hear the voices of familiar cultural figures who understood the experience and felt compelled to write or talk about it. I hoped their words might serve as trail markers for me.

I couldn’t find this book—in or out of print. I did find a few quotations that were gems, which I saved to reread. Those lines helped carry me through that difficult year—and confirmed what I had sensed early on: that a volume of quotations on pet loss should be out in the world. And so I got to work building the book I wanted to read. I started researching firsthand accounts of pet loss published over the last two centuries. I read journals and biographies, letter collections and memoirs, essays and articles. I listened to oral histories, interviews, and podcasts. I looked out for stories unfolding on social media.

I soon learned that the intensity of my grief for Snowflake was personal and specific, but not unique. Mourners documented their heartache over the loss of their cats, dogs, rabbits, birds, horses, mice, frogs, and other animals—even, in the case of Pablo Neruda, a mongoose. Nobel Prize-winning author V.S. Naipaul described the experience as “calamitous,” and writer May Sarton called it a “volcanic eruption of woe.” Poet Emily Dickinson was so bereft she asked for help: “Carlo died,” she announced in a letter to her friend Thomas Wentworth Higginson in January 1866. “Will you instruct me now?”

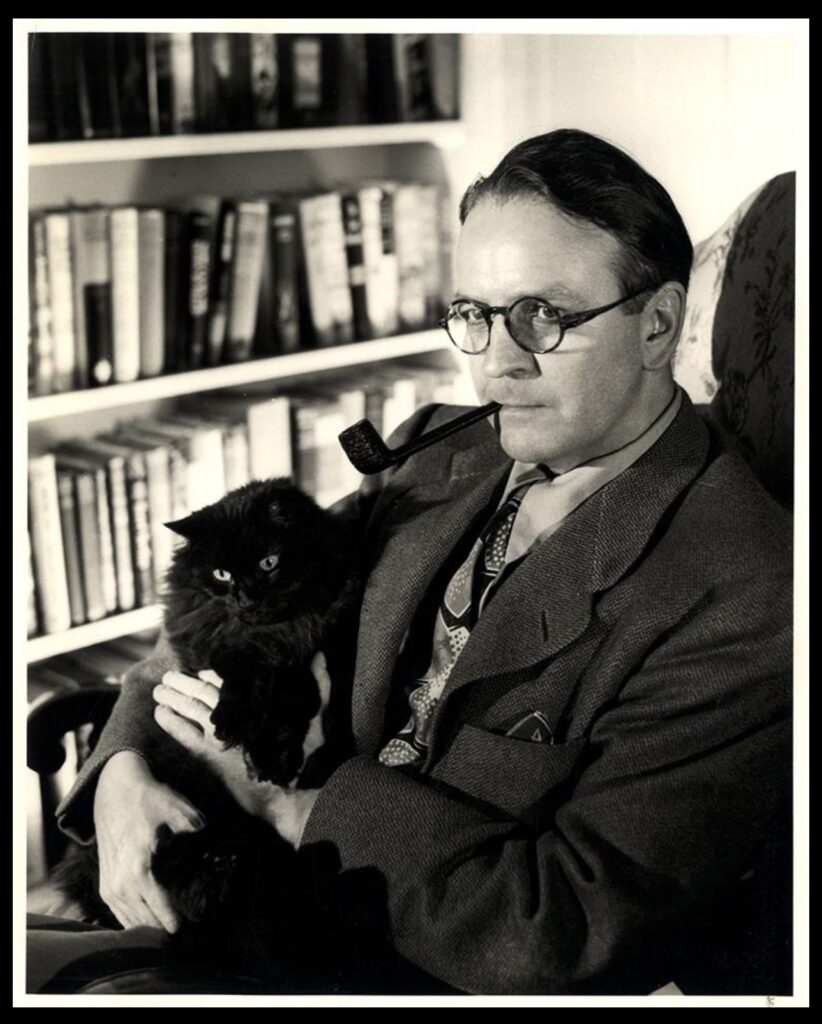

Again and again, I came across examples of mourners blindsided and leveled by the loss of a faithful friend. “Blemie’s death was a blow,” confessed the playwright Eugene O’Neill to a friend. “I knew I would miss him badly when he went, but I had no idea how badly.” Crime novelist Raymond Chandler and his wife were wrecked: “We were a bit broken up over the death of our black Persian cat. When I say a bit broken up I am being conventional. For us it was tragedy.” Cat behaviorist Jackson Galaxy offers this visual: “The immediacy of the loss blows through you as if you were an abandoned farmhouse.”

How do we make sense of the desolation that sets in so quickly? The bond is unlike any other relationship in our lives. When we’re kids, sometimes our dearest friend and closest ally is the family pet. “I can still see my first dog in all the moods and situations that memory has filed him away in . . .” recalled E. B. White. “For six years he met me at the same place after school and convoyed me home—a service he thought up himself.”

An animal’s love is deep, uncomplicated, unconditional, and forgiving, blessedly unburdened by the complexities of human dynamics. “Affection without ambivalence” is how Sigmund Freud described the connection. “No matter how awful the day, or how awful I am behaving at any given moment, George doesn’t care,” writes the journalist John Dickerson. “He finds me smoldering in my chair and dashes to my lap. Every dog is a rescue dog.”

How do we make sense of the desolation that sets in so quickly? The bond is unlike any other relationship in our lives.

Meanwhile, our daily routines are intricately intertwined. Together, over time, we establish rituals that are as steady as a metronome. And then, at the end, we are often in the position of deciding when to let them go—and if given the privilege, accompanying them in their final moments. It’s no wonder that we’re devastated when they depart; to be honest, it’s a small miracle that we find a way to continue on.

*

In a letter in 1863, Emily Dickinson described her Newfoundland, Carlo, as her “shaggy ally,” a perfect description that sounds like it could have been written today.

Our bond with an animal is often a private affair, but thankfully Dickinson and other brilliant minds were compelled to write about those friendships. Affection and respect shine through. Like a proud parent, Charles Schulz remembered how his childhood dog, Spike, was a language wizard and understood at least fifty words, including “potato,” which he would retrieve on command from the basement. P.G. Wodehouse explained how his tenderhearted Pekingese Squeaky intuitively deferred to her elderly sibling, Wonder. Not all animals are angels, though, and we also hear about maddening habits and domineering personalities.

In correspondence with friends, Raymond Chandler documented the antics of his imperious cat, Taki; and John Steinbeck lamented how his setter Toby “made confetti” out of almost half of the original Of Mice and Men manuscript, destroying two months of writing. One can’t help but wonder about the shredded draft of that now famous novel.

Animals can introduce chaos into our lives, but they are also uniquely capable of calming us down. Billy Collins and William Styron paid homage to the meditative ritual of the “head clearing” daily dog walk, and Doris Lessing described the sacred moment when she set aside “fret” and “urgency” to simply sit and be with her cat, El Magnifico. Perhaps poet

Mary Oliver summed it up best: “I think they are companions in a way that people aren’t. They’ll lie next to you when you’re sad. And they remind us that we’re animals, too.”

_________________________

WRITERS ON THEIR PETS

*

“I once heard a woman who’d lost her dog say that she felt as though a color were suddenly missing from her world: the dog had introduced to her field of vision some previously unavailable hue, and without the dog, that color was gone. That seemed to capture the experience of loving a dog with eminent simplicity.”

–Caroline Knapp*

“I placed an ad in the papers: ‘Lost: mongoose, answers to the name of Kiria.’ There was no reply. None of the neighbors had seen her. . . . She had disappeared forever. . . . I was grief-stricken for a long time.

–Pablo Neruda*

“Thank you so much for your kind & sympathetic letter about Toots. I really think that everyone who knew her grieves for her as if she were a real little person—& indeed was she not, & of the rarest kind?”

–Edith Wharton

Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University

Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University

*

“Our Christmas was not a particularly happy one, since we lost our black Persian cat that had been with us for almost twenty years, and was so much a part of our lives that even now we dread to come into the silent empty house after being out at night.”

–Raymond Chandler

Raymond Chandler: © John Engstead / mptvimages.com

Raymond Chandler: © John Engstead / mptvimages.com

*

“We all say to one another, ‘It never gets easier.’ Well, of course not; I would hope not, anyway. If it did, it would mean that it wasn’t the companion that died, but something inside us along the way.”

–Jackson Galaxy*

“One last word of farewell, dear Master and Mistress. Whenever you visit my grave, say to yourselves with regret but also with happiness in your hearts at the remembrance of my long happy life with you: ‘Here lies one who loved us and whom we loved.’ No matter how deep my sleep I shall hear you, and not all the power of death can keep my spirit from wagging a grateful tail.”

–Eugene O’Neill

Bettmann/Bettmann via Getty Images

Bettmann/Bettmann via Getty Images

_________________________

From Sara Bader’s The Book of Pet Love and Loss: Words of Comfort and Wisdom from Remarkable People. Used with permission of the publisher, Simon & Schuster. Introduction copyright 2023 by Sara Bader.