The series adaptation of Garth Risk Hallberg’s bestselling novel, City on Fire, premieres on Apple TV+ today, so we asked Hallberg about the uncanny experience of seeing his book come to life, handing over the creative reins (with “a license to kibitz”), ingenious acts of translation, and more.

*

How does it feel to see your characters and story come to life on screen?

There’s that scene at the end of Being John Malkovich where John Cusack is running around the interior of his mind, crashing through doors that join seemingly discrete times and places, an image that commingles comedy and intimacy and lunacy. I can say that stepping onto the City on Fire soundstages in the Bronx last summer felt a little bit like that. Like stepping into a large, persuasive, but slightly trippy externalization of the inside of my head.

On one of the stages was the apartment of Regan and Keith, mostly as I’d imagined it (making a few interior decoration allowances for the show’s time transposition from 1977 to 2003). But it was like: oh, wow, there are the photos just inside the door that Samantha notices, and there on the wall is some art by their six-year old daughter Cate. And here’s a report card from the Wenceslas-Mockingbird School. Surreal!

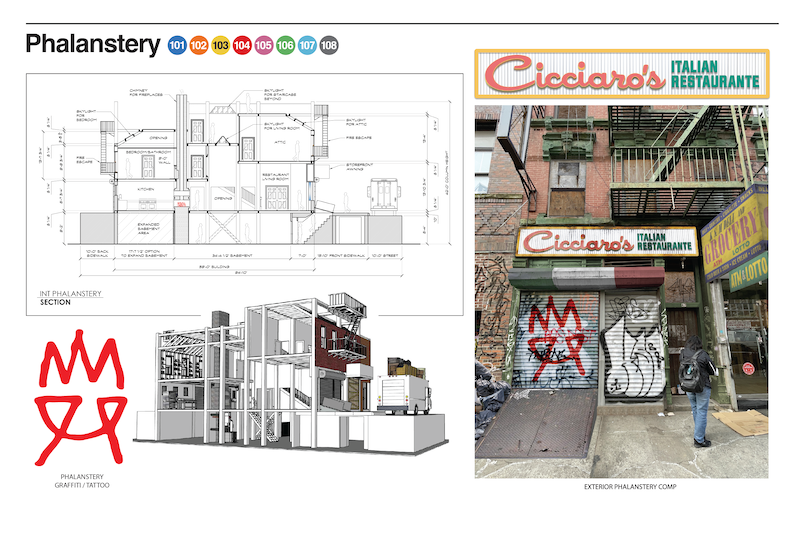

Uncanny soon gave way to cool, though. On the other soundstage, the production team had assembled a three-story, immersive version of the Phalanstery, the downtown squat where some characters from the novel do their dreaming and scheming. It was pretty much as I’d imagined it, except relocated from a brownstone in the East Village (’77) to a tenement on the Lower East Side (’03). The interior was so fully realized and so maximized for pothead goofing off that I didn’t want to leave. Apparently, neither did the actors (I was told it became the hangout during shooting breaks). And here came Max Milner as Nicky Chaos, climbing up the stairs in character to greet me. Or possibly to indoctrinate me into his Phalanx?

“Look book” image courtesy of Fake Empire Productions/Apple Studios

“Look book” image courtesy of Fake Empire Productions/Apple Studios

Freakier still was watching actors on those sets enact scenes from the novel—or scenes that expanded on the novel. Watching Wyatt Oleff deliver some poignant lines as Sam’s best friend, Charlie, I realized how much of myself I’d put into that character, and why. It messed me up for weeks after.

What notes or pieces of inspiration for the story/characters did you share with the creators?

I didn’t want to get too involved in the production process. I was deep into another book, for one thing, and I felt like I’d done what I wanted to do in City on Fire. Now, it should be out of my hands.

Also, as a novelist, I know zilch about how to make good TV. Not to say that you can’t be good at both (Richard Price, I’m looking at you), but they seem like very different skillsets. And I knew my showrunners, Josh Schwartz and Stephanie Savage, were good at making TV people like to watch.

I also have this intuition that the best adaptations arise more from a kind of parallax than from the literal-minded faithfulness you get in certain Masterpiece Theater series. It’s why Otis Redding’s is the best cover version of “Satisfaction,” for example. Why Miyazaki’s Howl’s Moving Castle is so good. I don’t think things should be too matchy-matchy between the book and film versions of a story—if it is, paradoxically, the adaptation won’t feel faithful. It’s part of why I loved the idea of shifting the action of City on Fire from post-fiscal crisis New York to the post-September 11th New York.

Still, I used my nominal role in the production as a license to kibitz, and when I felt like I had something to share, I shared it. There’s that term “compensation” that comes from literary translation, where you realize you have to lose an effect somewhere and then take steps to make up the difference elsewhere. Josh and Stephanie and I talked at length about a specific plot deviation from the book, which I endorsed, and I suggested a different plot move elsewhere that might create some of the same effect. To reveal the change would be a spoiler, but I was happy when they took the note.

In the Phalanstery with (clockwise from bottom left) Wonders, Savage, Schwartz, Milner; in the Lamplighter apartment with Savage and Schwartz. Polaroids courtesy of Angelica Lee; masks courtesy of Covid.

In the Phalanstery with (clockwise from bottom left) Wonders, Savage, Schwartz, Milner; in the Lamplighter apartment with Savage and Schwartz. Polaroids courtesy of Angelica Lee; masks courtesy of Covid.

Another example involves the character Regan. They had already written the bejesus out of the part, I thought, with the period update allowing her more room to express what in the book she has to repress. I thought it was one of the best roles in the script. And then when Jemima Kirke was cast, at the suggestion of director/producer Jesse Peretz, I thought of the rebellious energy Jemima brought to the role of Jessa on Girls and was like, “Wow, that could shed so much light on her relationship with her brother, William.”

So I just sent in a note for the team to bear in mind that “Regan has William energy in her,” meaning in this version, the two are more outwardly symmetrical, rather than complementary. In this case, they were a step ahead of me. I should add that I think Jemima absolutely crushed the role, from the first scene onward.

If you could play a minor role in the adaptation, what would it be?

I did get to play the tiniest of roles! The series (and its extension into the music-streaming world and limited-edition vinyl via the original soundtrack) is jam-packed with Easter eggs from the novel. The Italian restaurant that fronts the show’s Phalanstery, for example, is named Cicciaro’s in honor of Sam’s last name in the book (her dad there is an Italian American fireworks maker; in the show, a Chinese American fireworks maker.)

In the interest of verisimilitude, the office of Dr. Altschul, Charlie’s grief counselor, needed diplomas, which meant that Dr. Altschul needed a first name. Neither the production team nor I remembered I’d given him one in the book, so this is what they came up with: another Easter egg, of sorts.

Photo courtesy of Josh Schwartz

Photo courtesy of Josh Schwartz

What’s the hardest part of having your book adapted for film/TV?

Emotionally, this was a reasonably painless process for me compared to writing the book. Technically the hardest thing was figuring out the intersection with the music scene. The punk scene of mid-70s New York was so specific—such an ethos, almost—and is so central to the novel.

To be fair, New York was putting out some pretty good rock music in the time around September 11th—back in the day, Josh Schwartz had booked a lot of those bands to play at The Bait Shop on his show The O.C. (and a lot of them show up in the City on Fire soundtrack—the producers even figured out a way to have Sam go see the Yeah Yeah Yeahs). But how were we going to come up with the music Ex Post Facto would play, in a way that felt period-specific, authentic, and also like something Samantha might get obsessed with?

Music supervisor Jonathan Leahy broke down the process in the Times last weekend, which you can read about here—it sounds a little crazy, not to mention stressful! But when I saw episode 1, I was like, wow, this music is awesome and not that far from what I heard in my head.

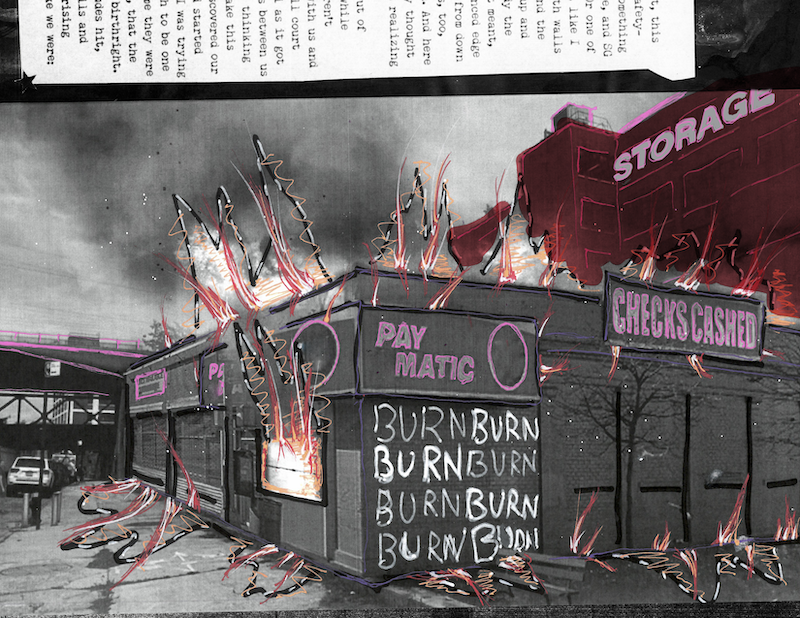

Another, related challenge had to do with Sam’s zine—how to update it and how to present it filmically. I delivered a hard drive with several gigs worth of amateurish photoshop files I’d used for the original zine to production coordinator Aaron Osborne. The text from the book was then expanded with new passages written for the series, and an Icelandic artist named Sara Gunnarsdóttir enlisted to do new illustrations as Sam. My paperback editor at Vintage Books liked the results so much that we briefly considered using them for the new paperback cover for the novel (left), before deciding to update Chip Kidd’s punkier hardcover version with type design from the show. I love how it turned out.

How has your relationship with the book changed during the process of adaptation?

In a novel, there’s a lot you can’t control, but there are so many things you can. You’re the actor, the director, the writer, the production coordinator. It is a great exercise to just give it over to someone else, or a bunch of someone elses—to trust what you made and give up that control.

It’s also a leap of faith, and one of the things I love about the result here is how shockingly faithful to the book the show City on Fire ended up being. You’ll see some deviations, some new things, particularly in Act II, but also some ingenious acts of translation, opened up by the daring leap forward in time. And in all the places that matter, it’s the same people, the same plot, the same city I love, the same longings and frustrations (even some of the same dialogue!), the same spirit, the same juxtapositions in tone…

Updated zine page courtesy of Fake Empire Productions/Apple Studios

Updated zine page courtesy of Fake Empire Productions/Apple Studios

After I watched episode 1, I wrote in a mash note to Josh and Stephanie: “It’s faithful not quite in the sense of integrity to a writer’s vision of the work (which is almost always no good on the screen) but in the sense of integrity to a reader’s.”

Stephanie wrote back, and consented to my sharing here: “What you get at about faithfulness is exactly what we love about long form narrative (formerly known as ‘TV’), and adaptation in particular. Writers, directors, actors and all the departments infuse the show with resonant (sometimes unexpected) elements of their own truth and, through the process, the series emerges as its own (hopefully wonderful) thing.”

____________________________

Garth Risk Hallberg’s City on Fire is available from Vintage.