Veterinarians have an unusual relationship with our patients’ mortality, as along with working to help animals live, we sometimes help them die. Like our human physician counterparts, we spend a good part of our time trying to stave off death, through preventive care, vaccinations, and care of severely ill and hurt animals; we do all we can to prevent and alleviate suffering. On the other hand, unlike physicians, we are regularly—sometimes daily—called upon to alleviate suffering through euthanasia.

As a veterinary student, I had struggled with the concept of it, and how easy it was to summon Death to end the life of a patient. Death seems to respect me, for he always responds to my requests for him to arrive, I journaled as a new graduate. At times he will arrive unbidden, and he and I will struggle over a creature … It is part of my job to dance with Death. People come to me to ask me to be a link for their animals, either to prevent Death, or to welcome him.

In other words, euthanasia kind of creeped me out. When I performed one, it felt as though I had been given privileged access to a special power I didn’t understand, that nobody understood. I didn’t know what to make of it.

While we did have an ethics class in veterinary school, the focus was mainly on legal situations. We were taught it would be unethical (and likely illegal) to agree to euthanize a client’s animal and instead find it another home without their permission, even if the animal was young and healthy. We did not discuss what it would feel like to euthanize an animal. I still remember a dog I treated as a new graduate that had been hit by a car.

My patient was in physiologic shock, which I threw myself into treating, managing to keep her alive. When she was stable, X-rays revealed that her pelvis was shattered, and her owners elected to euthanize her. Just hours after saving her life, I ended it. It was the first time, but not the last, that I had to swing from one extreme to the other on the same animal on the same day.

I regarded my own pets differently, knowing how little it would take for them to die.

Many people, including myself, get upset if a dog dies in a movie or a book; this is such a common phenomenon that a website exists called Doesthedogdie.com. The site has a searchable database of spoilers and content warnings for dozens of categories, all added after the initial category of death of a canine. But as a veterinarian, it’s not something I can avoid.

When I was new to performing euthanasia, it was the taking of a life that was challenging for me. I was amazed by how a simple intravenous injection could wield such enormous power over life and death. What was life, if you could end it so easily? At home, I regarded my own pets differently, knowing how little it would take for them to die.

As time went by, I became more accustomed to the concept. Many animals I euthanized were within days of dying on their

own, others were uncomfortable and suffering. I often felt I was performing an ethically honorable task: something my mother terms a mitzvah, a Hebrew word meaning a good deed, a sacred duty in the Jewish faith.

People sometimes ask whether a pet should view the body of a deceased animal housemate. I believe this is a good idea, although I also think the remaining animal usually already knows that its family member was ill, both by the sick pet’s behavior and by its smell.

I once performed an at-home euthanasia for a dog named Sal. The owners had placed their other dog, Louie, in a separate room while I euthanized the sick dog. After Sal died, they went to retrieve Louie. I sat on the side of the room farthest from the door, next to Sal’s body. As Louie entered the room, he raised his head and sniffed the air. Then his entire body language changed.

He knew instantly, likely from a smell indistinguishable to the human nose, that Sal had died. In that situation, many humans would likely approach the body, needing to look closely or even to touch the deceased animal to realize death had occurred. I have rarely seen an animal do that. They appear to gather this information from several feet away. Animals understand death far more than we give them credit for—and, quite possibly, better than people.

At the clinic one day, the receptionist handed me a patient’s chart and asked if I could do a euthanasia. It was scheduled for the other doctor, but she was backed up with an emergency, and the client didn’t have a preference regarding which doctor performed the procedure. Euthanasia often happens with no time for a doctor to mentally prepare. It’s not uncommon for an appointment with a very sick or injured animal to end with euthanasia.

I entered the exam room and found a middle-aged woman and her teenage daughter sitting on the floor. The patient, a very old kitty named Cleo, was wrapped in a towel in the woman’s lap. I sat on the floor with them. This is how a euthanasia begins for me, with getting onto the client’s level as best I can. Sometimes it is a client and a pet I know well, and sometimes they are complete strangers.

I stroked Cleo’s head and remarked upon how soft and beautiful her fur was. I gently asked the client how Cleo had been doing lately, and she described a lack of appetite, vomiting, and general discomfort. I noticed the wasted muscles, the protrusion of bones on the cat’s body. We talked about what a wonderful pet she had been and what a long life she had enjoyed. Both the woman and her daughter seemed comfortable with Cleo being euthanized.

Next, I asked if they had ever witnessed a euthanasia before. It’s a question I often ask, and my purpose is to gauge the owner’s comfort level with what is about to happen. It’s an opportunity for the person to let me know if they are nervous, so I can give them some additional reassurance and answer any questions they may have. I explained that the injection is a painless overdose of anesthetic, but I felt Cleo would be more comfortable if I gave her a tranquilizer injection first, so she wouldn’t be stressed when I placed the tourniquet on her leg and gave the intravenous injection.

I told them Cleo’s eyes would likely stay open, and she might urinate and defecate afterward as her muscles relaxed. I explained that I would check Cleo’s heart to make sure she was gone and that they mustn’t worry if they saw any twitches or muscle spasms. I let them know that, after the procedure, they could stay in the room with Cleo for as long as they liked.

Cleo barely noticed the tranquilizer injection and shortly afterward placed her head down in the woman’s lap as she lost consciousness. I gently picked up Cleo’s front paw and shaved some fur so I could visualize her vein. I set the fur aside on Cleo’s towel and told her people that, if they wanted, they could take it home as a keepsake (many owners appreciate this, although some comment wryly that they have plenty of fur at home).

Next, I placed the rubber tourniquet around Cleo’s front leg and tightened it. I put alcohol on the leg to better see Cleo’s vein. I made my silent prayer that all would go smoothly for Cleo and her family, setting my intention of doing my best for them. And I inserted the tiny needle into her vein. When I knew the needle was in place, I released the tourniquet and began injecting the euthanasia solution.

Just as I gave the injection, Cleo’s owner looked at me with moist eyes. “This must be so hard for you,” she said. I was stunned by her compassion, at the very moment of her cat’s death.

Yet I was unable to admit the truth even to myself. I didn’t say, “Yes, it’s hard to bear witness to so much love, so much gratitude, so much grief.” I didn’t say, “I feel a lot of pressure for things to go smoothly” or “I can never allow my emotions to interfere with my work.”

Instead, I told a small lie.

I said, “I only do it when I believe it is the right thing to do.”

Cleo died peacefully. When the injection was finished, I withdrew the needle, carefully placing a cotton ball over the leg to catch any bleeding. I put my stethoscope on and listened for Cleo’s heartbeat. I heard only the gentle rustle of the heart’s contents as the blood settled and came to rest.

“She’s gone,” I said softly after a moment. We all stroked Cleo’s soft fur and told her what a good kitty she’d been.

“She’s so peaceful,” her owner observed quietly.

“Yes,” I replied, “people often say that. They really do look peaceful.”

Most veterinarians have heard the statement uttered by Cleo’s owner countless times. Even more common is the statement, “I would love to be a veterinarian, but I know I could never put an animal to sleep.” People mean well, and are often grateful, yet it’s an isolating feeling to be told repeatedly that a critical element of your work is unimaginable. Which is probably why I lie.

I am always conscious of the fact that my voice will be the last voice the animal hears, and my touch will be the last touch.

My statement to Cleo’s owner, I only do it when I believe it’s the right thing to do, is something I’ve repeated to myself as well as to clients. It is mostly true. It is often true. But it is not always true. In addition to the healthy shelter dogs I euthanized early in my career, I have euthanized clients’ animals that could have lived if they were treated. Faced with a sick or injured animal the client can’t afford or doesn’t want to treat, I ask myself, would this animal be adoptable? Typically the answer is no. And because I’m aware that even healthy adoptable animals are euthanized at shelters every day, I am able, however unhappily, to proceed with a difficult and emotionally painful task.

This is the reason I will always adopt from rescues or shelters. I couldn’t save those lives, but I will save other ones.

Eventually I grew accustomed to the process of ending a life through euthanasia. It was a bit like adjusting to performing surgery—how strange did it feel, initially, to have my hands (gloved, of course) inside the body of one of my patients? To see and feel their internal organs, to cut and sew tissue and skin? It took some getting used to.

After a while, surgery was just another day at the office. Euthanasia, however, is unique. For myself and, I imagine, most

veterinarians, there will never be “ just another euthanasia.” Each one entails being fully present, as a sign of respect—for life, for death, for the individual being, for their human family. If the owner is not present for the procedure I can focus all my attention on the animal. I am always conscious of the fact that my voice will be the last voice the animal hears, and my touch will be the last touch; I am aware that the veterinary assistant or technician holding the animal feels the same way. We don’t speak about this, but it is always the case, no matter who I am working with.

If the animal’s owner is present, I experience another dimension of awareness: I am hypersensitive to the person’s emotional state. I know that the same act I perform to relieve an animal’s pain can cause profound suffering on the part of their human family. Part of the reason I adjusted to performing euthanasia was the patients themselves.

Animals, I have come to believe, do not fear death as most people do. They try to avoid it, certainly. Like humans, they have a survival instinct, which can be fierce. Yet when I see animals in the process of dying, they seem to experience a calm acceptance. And by acceptance, I do not mean resignation; I mean recognition and acknowledgment. I mean a true, full comprehension of mortality.

__________________________________

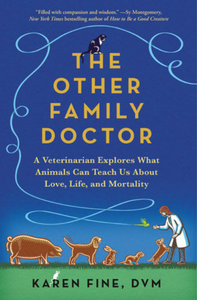

Excerpted from The Other Family Doctor by Karen Fine. Copyright © 2023 by Karen Fine. Published by arrangement with Anchor Books, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.