I have a fairly large crime fiction library at home and had access to a vastly larger one still for several years while I was working days at the Center for Fiction, in the old building on Forty-Seventh Street, just shy of the diamond district, which you crossed through on your way to and from the subway and where, in the afternoons, when the diamond hawkers were settled in and feeling good, they would give you a look up and down and decide whether you were a better prospect to buy or to sell. It was a really impressive collection, the Center for Fiction’s. They still have it, only it’s in Brooklyn now, moved by the greater forces of New York City real estate, itself the irrepressible catalyst of many a good and memorable crime fiction.

All that’s just to say that I’ve had access to thousands of crime novels and mysteries over the years and have been at occasional leisure to wander through the stacks picking up whatever caught my eye, reading for a few minutes or hours, then putting books away based on some arbitrary set of criteria I had formed or half-formed in my mind. The criterion I chose most often, typically but not always with a feeling of wry transgression, was whether that particular novel—novels of darkness, despair, and suffering—made me laugh. It’s a weakness. I love funny crime novels. It might be fair to say I’m obsessed with them and am always on the lookout for new stuff, like the diamond hawkers on Forty-Seventh Street.

But maybe first we should take a step back and define what’s meant by the terms, since I aim to do what the headline of this article suggests, finding the funniest crime novel ever written. Then again how can you define funny? The very act—breaking down the concepts inherent, removing the gags from their context, their subjective reception—is itself deeply, inevitably unfunny. Better, maybe, simply to take a look at the contenders and throw them into collision.

I always start with Patricia Highsmith, which I’m assured by knowledgeable, informed readers is a ludicrous selection, an utter and wholesale misreading of the author’s work, which I’ll accept, but to me she’s still funny, mordantly so. Find yourself in the mind of chronic killer Tom Ripley, working through all the reasons why his next murder is so utterly unavoidable, the culmination of a series of decisions and small prudent measures at least partially outside his control, and I dare you not to crack up. But for the purposes of argument I’ll allow that Highsmith can’t possibly be the answer to the question posed at the top, so how about somebody who actually intended to write at least partial comedy?

Donald E. Westlake and Lawrence Block, longtime friends and unbelievably prolific authors, were both, for my money, at their funniest when writing about burglars. Let’s say for Westlake The Hot Rock might be his funniest and for Block, we’ve got a wide selection across different series and eras, continuing today, but I’m partial to the Bernie Rhodenbarr books, and the one where Bernie acquires a bookshop with his burglary loot always gets me in particular, The Burglar Who Liked to Quote Kipling, not least for its trenchant analysis of Kipling and his adorants.

But now I’m noticing something—that both of these are New York City novels. So maybe the humor has something to do with geography, in these examples the stomping grounds of more or less sophisticated thieves in 1970s and 80s Manhattan. Maybe that’s a principle or rubric we should consider more broadly—comedy wrapped up with geography. And in that case, there’s really no denying the funniest location for a crime novel is Florida. Ideally southern Florida, but we could go as far north as Port St. Lucie.

So let’s start again with Elmore Leonard, who I consider to be one of the best, wittiest writers working in any genre, in any era, but whose humor I tend to think of as coinciding with and in many cases identical to his characters’ enormous vitality, which in the world of Leonard, is chiefly reflected in their ability to talk. (Here’s a recording where Leonard describes a bit of craft, namely that when he invents a character, he finds out whether they can talk; if they can, they’ll get more story time; if they can’t, he kills them, often pretty unceremoniously.) What that means, in effect, is that the characters themselves get all the best lines. That doesn’t undermine in the least Leonard’s case, it’s just an observation.

For a novel that includes both character-driven, character-dictated humor as well as a more authorial, all-encompassing, incessantly wild humor, I’d recommend Maximum Bob, about a crooked West Palm Beach judge who likes to impose the harshest sentences available, but then also has some incredibly tender, bizarre moments of insight contemplating mermaid shows and alligators in his yard. Or really any of the Florida Leonard novels will pretty consistently make you laugh, sometimes just at the sheer audacity of the storytelling: LaBrava, Gold Coast, Cat Chaser, and a few others—you can take your pick.

But there’s more to Florida than Leonard, of course, which brings us to the author who probably comes first to mind when thinking of wacky Florida crime humor, Carl Hiaasen, and it’s true, pretty much without exception all of Hiaasen’s novels are smart, robustly funny novels, especially, I would say, Bad Monkey and Tourist Season. Nobody has ever more fully embraced the worthwhile literary project of capturing the uncanny, irrepressible essence of Florida like Hiaasen has.

Except that while we’re on the subject, I’d also like to make a brief case for Charles Willeford as the ultimate scribe of Florida’s bizarre brand of noir, an author whose work is laced with one of the sharpest wits mystery ever saw, and who put it to such unforgettable use in, amongst others, and The Burnt Orange Heresy, the latter of which taps into some of the same veins as Patricia Highsmith did in the Tom Ripley series, but I’ve been all but forbidden from discussing that strand of crime fiction, so let’s move on. While we’re in the environs of Miami, I’ll also note that Vicki Hendricks’ Miami Purity might be one of the most sordid, madcap and fully imagined crime novels of all-time.

And that’s not even getting into any of John D. MacDonald’s novels, both the standalones and the Travis McGee stories, which have so many moments of sublime poetry amidst the intrigue and the hustles and the scams—moments that take your breath away and make you shake your head in admiration and wonder. So maybe we just give the title to the many authors of South Florida, en masse?

But wait, I’m not ready to finish thumbing spines, and now my memory is talking me back to that first trip I made through the stacks at the old Center for Fiction library on Forty-Seventh Street, after I’d made it through the diamond hawkers and put my work aside for the day and let my whims takeover. Walter Mosley’s Devil in a Blue Dress was the first crime novel I plucked out, almost by chance, and it was, unsurprisingly, the book that showed me everything crime fiction could do. I’m not going to sit here and tell you that Easy Rawlins and his misadventures trying to chase after Daphne Monet is, in the traditional sense, funny, but I will say that it represents a connective tissue with the classic noirs, I’m thinking about Chandler and Macdonald in particular, where a put-upon detective faces the injustices of the world and the sins of all families with a romantic world-weary sigh that now and again translates into a laugh, or a line so wickedly sharp it takes you aback, and that’s something like a joke, too, isn’t it?

I’m going to throw into this category of crime novel a few other authors who don’t fit neatly into the conversation, and I’m going to think of them all as the inheritors of Roberto Bolaño, who himself so admired Mosley’s work. Those authors are Santiago Gamboa, the Colombian author, and Horacio Castellanos Moya, the Honduras-born Salvadoran novelist, and in particular to his brief masterpiece, The Dream of My Return. Neither is truly a crime novelist, but both are wickedly, tragically funny about the fate of exiles walking the mean streets of the Latin diaspora.

Hold on, a few more. What about Lisa Lutz’s The Spellman Files, or any of the other five novels that followed in the series, offering up a Tennenbaum-like and uproariously tilted perspective on the traditional PI novel. Or Jonathan Lethem’s The Feral Detective, while we’re looking at contemporary madcap detectives. Or others, whose work I’ve found no particular way to shoehorn into the discussion but can’t be left out:

Janet Evanovich (New Jersey’s own Stephanie Plum, lingerie-buyer turned bounty hunter), Ross Thomas (DC politics as the Florida of the professional imagination), Sue Grafton (who turns Macdonald’s Santa Teresa onto its head), Rubem Fonseca (an author whose work is so hard to find in the United States these days, but whose stories and novels always involve a frenetic, crazy embrace of life in modern Brazil).

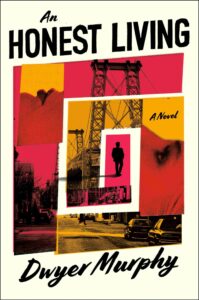

I ought to stop there, or somewhere. I’ve got my own novel to shill, An Honest Living, which begins, invariably I suppose, in the stacks of a private library on Forty-Seventh Street and follows an accidental detective through a nighthawk odyssey of New York and a mystery that involves a lot of rare books, obsessives, artists, real estate schemers, and lonelyhearts who just want to dance.

It’s not the funniest crime novel ever (I’m going to undermine this whole operation and say that title belongs to Highsmith’s second Ripley novel, Ripley Underground), but hopefully some of my appreciation for the tradition shines through. What could be funnier than an earnest attempt followed by spectacular failure?

______________________________

Dwyer Murphy’s An Honest Living is available July 26 from Viking.