Criticism of economic growth is almost as old as the phenomenon of economic growth itself. But the term “degrowth,” as it is used today, can be traced to relatively recent beginnings. Let us take a short look at its history.

Some traditions of growth criticism date back to the late 18th century and ranged from Luddite riots against the machines of industrialization to romantic unease with modernity or anti-colonial dissections of European civilization. Yet, in the second half of the 20th century, changed public perceptions of the finiteness of resources on this planet also led to a popular surge in critiques of economic growth.

The first report to the Club of Rome in 1972 initiated a global debate on “The Limits to Growth” which has not yet subsided. The birth of the word décroissance, translated into English as “degrowth,” can also be dated back to the year 1972. The political theorist André Gorz already asked at that time: “Is the earth’s balance, for which no-growth—or even degrowth—of material production is a necessary condition, compatible with the survival of the capitalist system?’”

Other intellectuals of this period influenced the early degrowth discussion—particularly important was the Romanian-American mathematician and economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen, who integrated an understanding of physics and thermodynamics into economic theory.

Degrowth was formed as a political project to open up cracks for systemic alternatives.

The debate on growth at the time extended far beyond environmental movements and included governments of industrialized countries, trade unions, and anti-colonial debates about development. One aspect of current degrowth ideas has been, for example, articulated by US revolutionary intellectuals and civil rights activists James and Grace Lee Boggs, who argued in 1974 that “the revolution to be made in the United States will be the first revolution in history to require the masses to make material sacrifices rather than to acquire more material things,” because, they continue, these were “acquired at the expense of damning over one-third of the world into a state of underdevelopment, ignorance, disease and early death.”

Still, during this time, the term “degrowth” was rarely used, and did not become a frame for a wider set of ideas until much later—and with the end of the oil crisis and the rise of neoliberalism since the 1980s, broader criticism of economic growth receded into the background.

This only changed in the early 2000s. At the height of the neoliberal penseé unique (Margaret Thatcher’s “There is no alternative”) and the hegemony of “sustainable development” in environmental debates (the claim that economic growth can be reconciled with sustainability), degrowth was formed as a political project to open up cracks for systemic alternatives. In 2002, a special issue of the French magazine Silence was published with the title “Decroissance soutenable et conviviale” (sustainable and convivial degrowth).

In the introduction of the issue, Bruno Clémentin and Vincent Cheynet coined the term décroissance soutenable explicitly as a counter-term to “sustainable development,” the buzzword at the time. In pairing the words “degrowth” and “sustainability,” the authors highlighted the fact that ending the pursuit of growth should not point to collapse or recession—as the word “degrowth” may suggest to many—but to a democratic process of transformation to a more just, sustainable, and less material and energy intensive society.

And the reference to degrowth as “convivial” (a French term, based on Latin con vivere, to live together) emphasized that it referred to a positive vision of the good life defined by cooperative social interrelations with each other and with nature, a vision insisting that another world is indeed possible.

“Degrowth” was both a provocation and a political proposal meant to challenge mainstream economic assumptions of development and to lay out a path for the future.

In this new use of the term, “degrowth” was both a provocation and a political proposal meant to challenge mainstream economic assumptions of development and to lay out a path for the future. Initially, it combined two intellectual strands: first, a socio-metabolic and thermodynamic analysis of capitalist growth, which highlighted the need for the countries of the Global North to exit the irrational and unsustainable growth race and subvert the related hegemony of the “growth paradigm” that claimed GDP growth was good, imperative, and limitless; second, the radical critiques of the “post-development” school of thought, which criticized capitalist “development” and the idea that progress requires growth as a misguided, destructive, and universalizing Western ideology.

The term gained currency in France in the following years, especially through the work of French economist, philosopher, and critic of development Serge Latouche. By 2008, the English term “degrowth” had received international attention, with the first “International Degrowth Conference on Ecological Sustainability and Social Justice” in Paris. From this point onwards, the degrowth concept spread from France to Spain, Italy, the rest of Europe, and beyond.

In its origins, the movement was rooted in anarchist environmental groups, campaigns for car-free cities and against large-scale industrial infrastructure, as well as in local collective projects such as collective housing groups and eco-villages. Yet it was the biannual International Degrowth Conferences which served as meeting points, places for discussion, and the slow formation of an international degrowth framework. In 2014, the Fourth International Conference in Leipzig attracted 3,000 participants.

By 2020, the Seventh International Conference, held online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, attracted over 4,000 participants. Research on the subject has multiplied, with hundreds of peer reviewed academic journal articles being published on the topic. Each year, degrowth summer schools organized by different institutes and collectives across Europe attract dozens and sometimes hundreds of participants, and the Global Degrowth Day in June is an opportunity for local organizations and initiatives to organize festivals and conferences around the world.

Degrowth’s critiques, and its core proposals should form an integral part of the larger ‘movement of movements’ that is necessary for a globally just future for all.

While degrowth continues to be a largely academic and activist concept, the critique of growth as an overarching priority is gaining popularity in the public realm as well. While polls have to be taken with a grain of salt, a 2018 poll taken in France showed that 54 per cent of respondents supported degrowth, compared to 46 per cent who supported green growth; in another poll, also in France, 55 percent of respondents were for a degrowth future, compared to 29 per cent who preferred a more secure, stable continuation of the present and 16 per cent who were for a neoliberal, digitized future.

In another poll, a majority of Europeans agreed that the environment should be a priority, even if that hampered economic growth. Surveys such as these do not necessarily translate to, for example, voting patterns—it is still hard to imagine a degrowth party taking double-digit percentages of the vote in French or let alone European elections. But they are an indication of the fact that there is some concern and receptiveness by the public, and that there could be room for degrowth to prosper and develop further as a new eco-social common sense competing against eco-modernist and green growth ideas.

Research on degrowth is by now quite diverse and empirically robust. It spans disciplines such as economics and the humanities, political science, climate sciences, technology studies, and some natural and engineering sciences, and it includes hundreds of scientific articles on issues ranging from economic modeling to analyses of international socio-metabolic datasets, to case studies of squats in Barcelona.

More and more books for a general audience are being published in English on the subject since 2014, as well as dozens of edited books and special issues that focus on diverse topics such as housing, technology, political economy, tourism, food, democracy, social movements, feminism, anthropology, and history.

However, while degrowth goes beyond the ecological and economic perspectives that are dominant in the literature, there is not much writing that explores degrowth in its full breadth, including analyses from the social sciences and humanities centre stage. And while the degrowth movement is clearly progressive or even largely anti-capitalist, there are few books exploring degrowth from a perspective explicitly critical of capitalism that engages with wider debates on the left—that is, one that sees systems of domination such as patriarchy, colonialism, imperialism, racism, and capitalism as the central, structural problems facing us today.

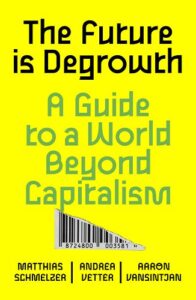

This is what we seek to do in The Future is Degrowth. In doing so, we argue that degrowth represents a crucially important, and internally coherent, framework for just futures—one that must supplement and possibly transform progressive proposals like the Green New Deal. While “degrowth” as a term need not be taken up by emancipatory social movements and the broader left, we argue that its perspectives, its critiques, and its core proposals should form an integral part of the larger “movement of movements” that is necessary for a globally just future for all.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Future Is Degrowth: A Guide to a World beyond Capitalism by Matthias Schmelzer, Aaron Vansintjan, and Andrea Vetter. Copyright © 2022. Available from Verso Books.