I grew up thinking I didn’t matter, that no one cared what I had to say. The world didn’t see me, a daughter of working-class Mexican immigrants, and what it did see, it considered disposable, inconsequential. I rarely found portrayals of anyone like me—bookish and poor and surly and Brown—in the art that I enjoyed.

I searched everywhere for a model for the life I wanted, but found few. I wanted to be a writer and travel around the world, but I had no idea how I was going to make that happen. I saw only snippets of that kind of life here and there.

Texts like the poetry of Sandra Cisneros were a lifeline. Here was a Mexican girl from Chicago who’d become a writer and traveled alone through Europe. But texts like hers were rare finds for me, because, it seemed, I was the only one in my immediate vicinity looking for them.

My teachers didn’t often teach books by people of color, and I didn’t have mentors or access to the internet, which was rudimentary at that time. The libraries in my community were so limited and hostile toward children that I began stealing books from the bookstore.

Today, of course, I know that there were other books out there at the time that spoke to who I was, but they didn’t make it into my hands very often. So when no template existed, I did what Lucille Clifton wrote about in her poem “won’t you celebrate with me” and made it up.

I rarely found portrayals of anyone like me—bookish and poor and surly and Brown—in the art that I enjoyed.

When I began writing about this life that I’d made up, I was plagued by a nagging voice that asked, “Erika, who the fuck cares?” The answer was always a memory of how deeply affirming it was for me to discover myself in the little art that declared a story like mine worthy. I wanted a place for myself in this tradition, and when I began seeking more texts of women writers while in college, I started to see where I fit in.

I consider Toni Morrison the patron saint of my writing. To write with her level of honesty and clarity is my North Star. Virginia Woolf is referenced in this book again and again, both for her work and for her tragic life, which, I suppose, are one and the same. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz became a model for my rebellion. And the list goes on and on.

None of my books could have been written without these extraordinary authors. I’m indebted to all the women who came before, those who paved the way as well as those whose talents were extinguished, buried, or sublimated because the world was afraid of their strength. It’s thanks to their rebellions, big and small, that I get to lead this extraordinary life—that is, a life completely of my choosing. I am myself in a world that pressures me to be otherwise, a world that doesn’t love me, wasn’t built for me.

Women of color are regularly praised for our resilience, but what’s too often overlooked is that our resilience is a response to so many forms of violence. For us, resilience is more than a noble trait; it’s a lifestyle that oppression has demanded of us. Either we adapt or we die.

*

It was October 2014, and I had fallen into the worst depression of my life, the darkness outside enveloping me in a crippling and unfamiliar despair. My therapist asked if I ever thought about suicide. I said no, but the truth was that I thought about it several times a day.

I’d rent a cabin in Michigan and off myself with a bottle of wine and a fistful of pills. I’d listen to the beautiful piano works of Erik Satie as I slipped out of consciousness and into a peaceful oblivion. I was never able to say it out loud.

Women of color are regularly praised for our resilience, but what’s too often overlooked is that our resilience is a response to so many forms of violence.

At thirty, my life was in shambles. I’d escaped my childhood to pursue the dream of becoming a writer, and here I was, a grown woman, paralyzed with hopelessness and self-doubt. All I could do was binge-watch Gilmore Girls, finding a sliver of comfort in the idyllic New England town of Stars Hollow, the benign and quirky characters, and the silly capers they got into. I loved watching the interactions between Lorelei and her daughter, Rory, because they were so unlike my relationship with my own mother.

As soon as I hit puberty, my mother and I began to resent each other. Our relationship was nothing like the wholesome white fantasies I saw on TV. I grew up in a working-class Mexican neighborhood that was plagued with violence and squalor. Sex workers and their clients loitered in front of a seedy motel at the end of our block.

Fun fact: the first penis I ever saw belonged to a man flashing a sex worker. My brother saw people literally having sex behind our building. Strange men snorted drugs off our garbage cans. Gangs were ubiquitous. Once, a man tore my mother’s gold chain off her neck and then slapped my brother until he fell to the ground when he tried to protect her.

I struggled to find a place for myself in this environment. I had always been an unusual kid; most of my family and my peers mis-understood me, disliked me, or both. Most girls my age looked like traditional Mexican daughters with their neat clothes and braided hair. Others wore more urban clothes—sneakers, basketball jerseys, and large hoop earrings. Meanwhile, I wore combat boots, flappy black dresses, and band T-shirts. I dyed my short hair funny colors.

When I “became a woman” and my sexuality began to flourish, I became a nuisance to my parents, particularly my mother. I had strong opinions that no one agreed with. I was a feminist, hated church, enjoyed solitude, and loved to read and write. I was always scandalizing my mother in some form or an-other. One of my earliest forms of rebellion was shaving my legs. I was thirteen and my dark hair was growing in thick as cactus spines. Embarrassed, I secretly used my dad’s razor in the shower.

One afternoon we were at a family party at my uncle’s house. It was summer and I was wearing a pair of overall shorts, and as I passed my mother sitting on the stairs, I felt her hand brush against my leg. “Hija de la chingada,” she muttered, her face flushed with anger.

Writing was the cheapest way to feel free.

I constantly complained about the unfair distribution of labor in our house. Why did I have to heat tortillas for my brother? Didn’t he have hands? Why couldn’t it be the other way around? And how come the men always ate first even though the women did all the work? To my mother’s chagrin, I was not at all interested in housework. Anytime she tried to teach me how to cook, it would end with me storming out of the kitchen, exasperated by her criticism and bored as hell by the minutiae of chopping onions, sorting beans, and frying tortillas.

My mother grew up in a wooden shack in rural Mexico. The daughter of a migrant worker in the Bracero Program in the United States and a frequently ill mother, she had to run the household and take care of her seven siblings. As the eldest daughter, she began cooking at the age of five, which might sound cute if the circumstances weren’t so depressing. She made tortillas from scratch and by hand. She was smart and driven but was only allowed a few years of schooling in her remote mountain village. She still laments that she was only able to complete sixth grade.

This resulted in a very narrow worldview, particularly when it came to gender norms. In 1978, at the age of twenty-one, she immigrated to the United States with my father. Two decades later, when her daughter began to act like an Americanized teenager, she was rightly bewildered, and reacted how any Catholic Mexican mom would—with unbridled control.

She wanted to know my whereabouts at all times, grew suspicious of me whenever I left the house. Though she was only trying to protect me, she always suspected the worst and did everything in her power to prevent me from getting pregnant and ruining my life. A fear I now understand.

The work of Sharon Olds, Anne Sexton, and Sandra Cisneros—women who wrote unapologetically about their bodies and inner lives—opened up a vast space inside me.

In the beginning, I just wanted room to breathe. After a while, though, I did in fact do the kinds of things she feared: I experimented with drugs, had sex, pierced body parts, and even got a shitty tattoo in some guy’s gross attic. I’d try anything to quell my restlessness. Once I punched a door after an argument with my parents. Sometimes I cut myself.

To escape the bleakness of my environment and my tense relationship with my mother, I lost myself in books. I latched on to writing. Writing brought me joy. I excelled at it and hoped it would offer me a way out.

I realize now that it was also convenient and inexpensive. All I needed was a pen and paper. I had many other interests—particularly art and music—but those required many more resources, money we didn’t have. My parents once bought me an acoustic guitar at a garage sale, but I soon gave up when we couldn’t afford lessons and I was unable to teach myself with library books.

Writing was the cheapest way to feel free. I was scrutinized and controlled at home, and the blank page offered me endless possibilities, a vehicle to create another reality for myself.

In high school a few teachers noticed my talent and encouraged me to keep writing. Mr. Celso, my freshman English teacher, was particularly supportive and would give me mixtapes and books he thought I’d like. Once he even made me a packet of all his favorite poetry. The work of Sharon Olds, Anne Sexton, and Sandra Cisneros—women who wrote unapologetically about their bodies and inner lives—opened up a vast space inside me. Writing felt like an emergency. And so I wrote poems about menstruation, sex, and sadness. And trees, of course. Always trees.

My sophomore year I got censored in our literary magazine for using the word “cunt.” Another time I was reprimanded for reading a poem about my vagina at a school assembly. I was scandalous like that.

____________________________________

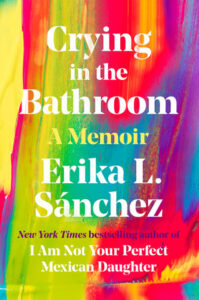

From Crying in the Bathroom, by Erika L. Sánchez, published by Viking, an imprint of the Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2022 by Erika L. Sánchez.