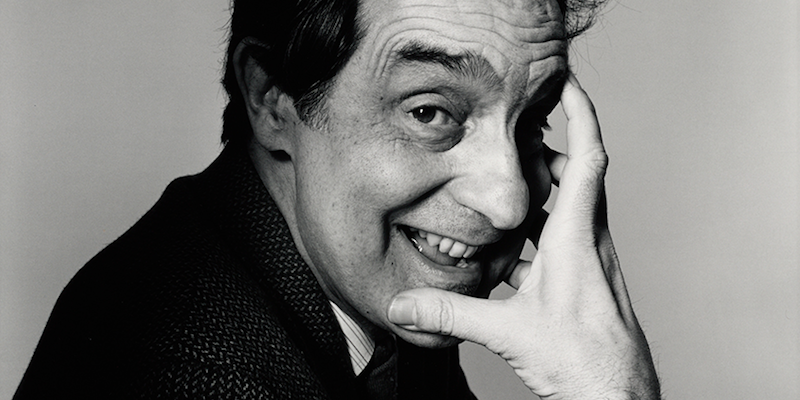

To speak of Italo Calvino’s popularity outside of Italy is to speak of Calvino in translation, given that he has been read and loved abroad in other languages and not in Italian. For an author who floats, as Calvino himself said, “a bit in mid-air,” translation—that twofold and intermediate space—was his destiny.

Let’s start with his Italian (or non-Italian) identity, an Italianness always tilting toward the Other. These are some biographical facts (with which he loved to play): he was born in Cuba, raised in San Remo—an extremely cosmopolitan city at the time—and married an Argentine translator. He lived for many years in France and traveled the world. It comes as no surprise that New York City, a perennial crossroads of languages and cultures, was the place he considered most “his.”

We should note the passion he felt, from the beginning, for non-Italian authors: the discovery of Kipling as a young man, and his baccalaureate thesis on Conrad, an author who, it so happens, wrote in a language he was not born into. Let’s bear in mind his friendship and collaboration with Cesare Pavese and Elio Vittorini, two fellow writer-translators who were also editors. These are just a few highlights of his formation as a writer before achieving worldwide fame.

More international than Italian, Calvino straddled places and languages and was acutely aware of what could be mined from a detachment from one’s own origins. Remember that he wrote his most mature works—those that were most celebrated, and therefore most widely translated—in France while experiencing, willfully, a fertile state of linguistic exile.

He was the translator of Raymond Queneau, a French writer known for his linguistic whimsy, though I would add that Le fiabe italiane, the Italian folktales he collected and adapted, were also a sort of translation.

More international than Italian, Calvino straddled places and languages and was acutely aware of what could be mined from a detachment from one’s own origins.

William Weaver, Calvino’s American translator, says in an interview with The Paris Review that Calvino was easy to translate because he wrote in a literary language: a universal idiom that lends itself naturally to translation. He adds, however, that it was also a challenge to replicate the careful rhythm of his prose, and that he would read passages from Invisible Cities out loud while he translated.

Weaver also understands Calvino’s passion for scientific language and for technical terms, which pose another hurdle for any translator, introducing yet another language, one that is rigorously specific, to his writing. This is my point: Calvino, a distinctly Italian writer, has never written purely in Italian. On the contrary, he had his own language— an expressive kingdom belonging only to him—as do all other important and interesting writers.

In his essay “To Translate Is the Real Way of Reading a Text,” Calvino speaks of the issue of multiplicity by referring to “different levels of language.” He argues that translation “requires a sort of miracle,” speaking of its “secret essence” as if it were an extract to distill with the proper equipment. He is attuned to issues of translation not only as a translator/writer, but as a man of letters who was also a scientist; this essential double nature underlies the way that he reflects on the problematic nature of translation. He writes: “True literature works along the un-translatable margins of every language.”

Perhaps the most startling observation in his essay is this: that due to the discrepancy between the spoken and written language, Italian writers “always have a problem with their own language [and they live] in a state of linguistic neurosis.” Calvino is able to identify this problem because he looks at Italian from both inside and outside, as if it were a foreign tongue, or in any case, like his character Mr. Palomar, from a measured distance. Calvino appreciated being translated not only to be read in more places, but also in order to “understand better what I have written and why.” Translation, for him, was a form ofγνῶθι σεαυτόν / gnōthi seauton, a revelatory process to see and know himself from a new angle, from a foreign and alienating perspective.

Invention and innovation are two terms often used by non-Italian critics regarding Calvino. Joseph McElroy, in his 1974 review of Invisible Cities in The New York Times, calls him “Italy’s most original storyteller.” In speaking of the novel, McElroy draws attention to the conversation between the emperor, Kublai Khan, and the traveler, Marco Polo. Plato’s dialogues come to mind; not surprisingly, the critic discusses archetypal forms, and concludes: “If they are forms, they are also like signals condensing in themselves power that awaits its translation into form. And Calvino’s book is like no other I know.”

Calvino, a distinctly Italian writer, has never written purely in Italian. On the contrary, he had his own language—an expressive kingdom belonging only to him—as do all other important and interesting writers.

Original is a term that inevitably refers to translation, pointing to the ongoing dynamic between the initial “primary text” and the new one, which is secondary, transformed. Original has to do with what is radical and, thus, with what is revolutionary. Calvino himself considered Invisible Cities his most popular book in America. Curiously, according to the author himself, it was also the furthest removed from the usual fare of American readers.

Anatole Broyard, who reviewed Marcovaldo, in 1983, also in The New York Times, is less enthusiastic than McElroy, though Broyard, too, describes Calvino as “the Italian writer who seems to cause the most excitement among American readers.” He compares Calvino’s fantastical writing to the rarefied images of de Chirico, another hybrid artist who cut across the spectrum.

He also mentions critics who describe Calvino’s project as an “emancipation”—a loaded term in the collective American conscience. He notes comparisons of Calvino with Gabriel García Márquez and Jorge Luis Borges, two Spanish-language writers of stratospheric impact. He concedes: “Mr. Calvino invents, but he does not persevere.” According to Broyard, Calvino’s most beloved book is If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. I see no need to belabor the apt but abused metaphor of the translator’s task as traveler.

Why was Calvino so loved outside Italy? I would point to the innovative language, the imagination that roamed and pushed forward, also the use of irony. In his review, Broyard maintains that Calvino’s use of irony is overvalued. I do not agree. Calvino was a master at playing with linguistic register, alternating between high and low, humor and seriousness, philosophy and fantasy, shifting from one literary genre to another. His objective-subjective gaze took in the world along with the cosmos, the everyday and the eternal.

In one of my student workshops at Princeton University, we translated his short story “Dialogue with a Tortoise,” a section that was cut from the novel Palomar. And this is why I can confirm just how much Calvino is still loved in America, even among younger readers. My students loved tackling a marvelously challenging text containing an avalanche of scientific terms and an effervescent sense of humor.

In the end, humor may be the hardest thing of all to translate well. The story unfolds emphatically in the form of a Platonic dialogue, or perhaps one by Leopardi. I believe that Calvino was always in dialogue with himself, with his shadow-twin, so as to see himself, as I have said, from a new perspective. He embodies, in this regard, the sensibility of the translator, who is always playing with two texts, two voices.

Calvino speaks directly about translation—a distinctly and exclusively human venture—in “Dialogue with a Tortoise.” Palomar tells the creature: “But even if we could prove that thoughts exist inside your retractable head, I must take the liberty of translating it into words to allow it to exist for others as well, besides yourself. Just as I am doing at this moment: lending you a language so that you can think your thoughts.”

In the workshop, I realized that the desire to translate Calvino, and to do it well, is born from his own precise language, which is never ambiguous, which serves as a solid mooring in the always ambiguous experience of translation—an act that remains, in the best of circumstances, an exploration. As the students and I tackled the text, we asked ourselves what Calvino would have made of Google Translate and other algorithmic forms of converting and changing language.

Calvino’s language—limpid-complex, intellectual-ironic, sober-playful—resonates in any language. Those who read it in translation find a blithe spirit, never provincial, always communicable, open to interpretation. It was his center of gravity—the floating gravitational center of an astronaut—that carried him past all kinds of boundaries and rendered him extremely translatable. The theme of lightness that he investigated with such subtlety toward the end of his life refers, above all, to his airy, multiple essence. Whoever reads Calvino in translation encounters a spirit inclined by definition toward foreign territories, or rather, allied to a linguistically porous environment.

Calvino is beloved outside Italy because the language he created contained all the necessary ingredients, that “secret essence” which produces, with exceptional results, the miracle of translation. Having had such a deep interest and such boundless generosity for other writers, especially those in translation, it seems right to me, even fated, that he was so warmly and sensationally received in the other languages of the world.

Rome, 2021, translated by Alberto Vourvoulias-Bush in collaboration with the author

______________________________________

Excerpted from Translating Myself and Others by Jhumpa Lahiri. Copyright © 2022 by Jhumpa Lahiri. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press