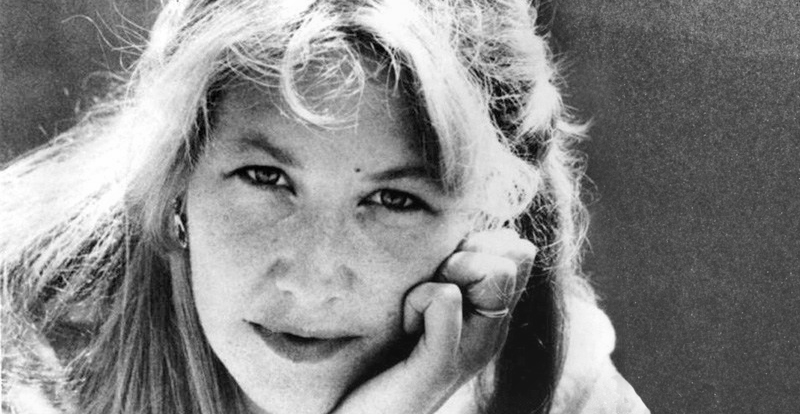

Annie Dillard, one of our best writers, is also one of our best teachers. We know because her students—and her readers—keep telling us. In Alexander Chee’s How to Write An Autobiographical Novel, Dillard appears as a generous, galvanizing teacher urging her students to envision their books on the shelves of bookstores. Maggie Nelson, asked in The Rumpus what writing advice she gives her students most often, cites Dillard. Kevin Barry, when asked about the best writing advice he’s ever received: “Annie Dillard said once that the only advice any writer needs is to keep your overheads low.” In celebration of her 76th birthday, here is an incomplete—but still sweeping—collection of some of Annie Dillard’s best writing advice.

Write to your own idiosyncratic interests:

Why do you never find anything written about that idiosyncratic thought you advert to, about your fascination with something no one else understands? Because it is up to you. There is something you find interesting, for a reason hard to explain. It is hard to explain because you have never read it on any page; there you begin. You were made and set here to give voice to this, your own astonishment.

Write as if you were dying. At the same time, assume you write for an audience consisting solely of terminal patients. What would you begin writing if you knew you would die soon? What could you say to a dying patient that would not enrage by its triviality?

–from “Write Till You Drop,” The New York Times, 1989

You are the only one of you . . . your unique perspective, at this time, in our age, whether it’s on Tunis or the tree outside your window, is what matters. Don’t worry about being original . . . Yes, everything’s been written, but also, the thing you want to write, before you wrote it, was impossible to write. Otherwise it would already exist. You writing it makes it possible.

–from “Annie Dillard and the Writing Life,” as recounted by Alexander Chee

Find inspiration through reading others:

Read for pleasure. If you like Tolstoy, read Tolstoy; if you like Dostoevsky, read Dostoevsky. Push it a little, but don’t read something totally alien to your nature and then say, “I’ll never be able to write like that.” Of course you won’t. Read books you’d like to write. If you want to write literature, read literature. Write books you’d like to read. Follow your own weirdness . . .

The more you read, the more you will write. The better the stuff you read, the better the stuff you will write. You have many years. You can develop a taste for good literature gradually. Keep a list of books you want to read. You soon learn that “classics” are books that are endlessly interesting almost all of them. You can keep rereading them all your life about every ten years and various ones light up for you at different stages of your life.

–from advice sent to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill students, republished in Image Journal

Hemingway studied, as models, the novels of Knut Hamsun and Ivan Turgenev. Isaac Bashevis Singer, as it happened, also chose Hamsun and Turgenev as models. Ralph Ellison studied Hemingway and Gertrude Stein. Thoreau loved Homer; Eudora Welty loved Chekhov. Faulkner described his debt to Sherwood Anderson and Joyce; E. M. Forster, his debt to Jane Austen and Proust. By contrast, if you ask a 21-year-old poet whose poetry he likes, he might say, unblushing, ”Nobody’s.” He has not yet understood that poets like poetry, and novelists like novels; he himself likes only the role, the thought of himself in a hat. Rembrandt and Shakespeare, Bohr and Gauguin, possessed powerful hearts, not powerful wills . . . They learned their fields and then loved them. They worked, respectfully, out of their love and knowledge, and they produced complex bodies of work that endure. Then, and only then, the world harassed them with some sort of wretched hat, which, if they were still living, they knocked away as well as they could, to keep at their tasks.

–from “Write Till You Drop,” The New York Times, 1989

In writing, action is everything:

Don’t use passive verb constructions. You can rewrite any sentence.

–from Image Journal

How do we get vivid writing? Verbs, first. Precise verbs. All of the action on the page, everything that happens, happens in the verbs. The passive voice needs gerunds to make anything happen. But too many gerunds together on the page makes for tinnitus: Running, sitting, speaking, laughing, inginginginging. No. Don’t do it. The verbs tell a reader whether something happened once or continually, what is in motion, what is at rest. Gerunds are lazy, you don’t have to make a decision and soon, everything is happening at the same time, pell-mell, chaos. Don’t do that. Also, bad verb choices mean adverbs. More often than not, you don’t need them. Did he run quickly or did he sprint? Did he walk slowly or did he stroll or saunter? . . .

Adverbs are a sign that you’ve used the wrong verb. Verbs control when something is happening in the mind of the reader. Think carefully—when did this happen in relation to this? And is that how you’ve described it?

–from “Annie Dillard and the Writing Life,” as recounted by Alexander Chee

When in doubt, return to the specific and concrete:

Always locate the reader in time and space again and again. Beginning writers rush in to feelings, to interior lives. Instead, stick to surface appearances; hit the five senses; give the history of the person and the place, and the look of the person and the place. Use first and last names. As you write, stick everything in a place and a time.

Don’t describe feelings.

The way to a reader’s emotions is, oddly enough, through the senses.

–from Image Journal

If your writing confuses you, investigate the confusing part:

Push it. Examine all things intensely and relentlessly. Probe and search each object in a piece of art; do not leave it, do not course over it, as if it were understood, but instead follow it down until you see it in the mystery of its own specificity and strength. Giacometti’s drawings and paintings show his bewilderment and persistence. If he had not acknowledged his bewilderment, he would not have persisted.

–from “Write Till You Drop,” The New York Times, 1989

Spend it all now. Don’t save your best ideas for later:

Spend it all, shoot it, play it, lose it, all, right away, every time. Do not hoard what seems good for a later place in the book, or for another book; give it, give it all, give it now. The impulse to save something good for a better place later is the signal to spend it now. Something more will arise for later, something better. These things fill from behind, from beneath, like well water. Similarly, the impulse to keep to yourself what you have learned is not only shameful, it is destructive. Anything you do not give freely and abundantly becomes lost to you. You open your safe and find ashes.

–from “Write Till You Drop,” The New York Times, 1989

When in doubt, cut the top . . .

Usually you will have to rewrite the beginning the first quarter or third of whatever it is. Don’t waste much time polishing this; you’ll just have to take a deep breath and throw it away anyway, once you finish the work and have a clearer sense of what it is about. Tear up the runway; it helped you take off, and you don’t need it now. This is why some writers say it takes “courage” to write. It does. Over and over you must choose the book over your own wishes and feelings.

–from Image Journal

It is the beginning of a work that the writer throws away.

A painting covers its tracks. Painters work from the ground up. The latest version of a painting overlays earlier versions, and obliterates them. Writers, on the other hand, work from left to write. The discardable chapters are on the left. The latest version of a literary work begins somewhere in the work’s middle, and hardens toward the end. The earliest version remains lumpishly on the left; the work’s beginning greets the reader with the wrong hand . . .

Sometimes the writer leaves his early chapters in place from gratitude; he cannot contemplate them or read them without feeling again the blessed relief that exalted him when the words first appeared—relief that he was writing anything at all. That beginning served to get him where he was going, after all; surely the reader needs it, too, as groundwork. But no.

–from The Writing Life

. . . and in general, cut ruthlessly:

Don’t use any extra words. A sentence is a machine; it has a job to do. An extra word in a sentence is like a sock in a machine . . .

The work’s unity is more important than anything else about it. Those digressions that were so much fun to write must go.

–from Image Journal

One afternoon, at her direction, we brought in our pages, scissors and tape, and told to bring several drafts of an essay, one that we struggled with over many versions.

Now cut out only the best sentences, [Dillard] said. And tape them on a blank page. And then when you have that, write in around them, she said. Fill in what’s missing and make it reach for the best of what you’ve written thus far.

I watched as the sentences that didn’t matter fell away.

–from “Annie Dillard and the Writing Life,” as recounted by Alexander Chee

Point the reader to what’s important:

If something in your narrative or poem is important, give it proportional space. I mean, actual inches. The reader has to spend time with a subject to care about it. Don’t shy away from your big scenes; stretch them out.

–from Image Journal

Evaluating your work as you write is useless:

There is neither a proportional relationship, nor an inverse one, between a writer’s estimation of a work in progress and its actual quality. The feeling that the work is magnificent, and the feeling that it is abominable, are both mosquitoes to be to be repelled, ignored, or killed, but not indulged.

–from The Writing Life

Don’t compare yourself to your most productive friend:

Faulkner wrote As I Lay Dying in six weeks . . . Some people lift cars, too. Some people enter week-long dog-sled races, go over Niagara Falls in barrels, fly planes through the Arc de Triomphe. Some people feel no pain in childbirth. Some people eat cars. There is no call to take human extremes as norms.

–from The Writing Life

Remember publication is subjective:

Publication is not a gauge of excellence. This is harder to learn than anything about publishing, and very important . . . The market for hardback fiction is rich married or widowed women over fifty (until you all start buying hardback books). The junior editors who choose new work are New York women in their twenties, who are interested in what is chic in New York that week, and who have become experts in what the older women will buy in hardcover. Eight books of nonfiction appear for every book of fiction. The chance of any manuscript coming into a publishing house and getting published is 1 in 3,000. (Agents send in most of these manuscripts. Most agents won’t touch fiction.)

When a magazine rejects your story or poem, it doesn’t mean it wasn’t “good” enough. It means that magazine thought its particular readers didn’t need that exact story or poem. Editors think of readers: what’s in it for the reader? There is a cult of celebrity, too, in this country, and many magazines publish only famous people, and reject better work by unknown people.

You need to know these things somewhere in the back of your mind, and you need to forget them and write whatever you’re going to write.

–from Image Journal

Remember to live a life:

Dedicate (donate, give all) your life to something larger than yourself and pleasure to the largest thing you can: to God, to relieving suffering, to contributing to knowledge, to adding to literature, or something else. Happiness lies this way, and it beats pleasure hollow . . .

Never, ever, get yourself into a situation where you have nothing to do but write and read. You’ll go into a depression. You have to be doing something good for the world, something undeniably useful; you need exercise, too, and people.

–from Image Journal

Above all, keep working:

Talent isn’t enough . . . Writing is work. Anyone can do this, anyone can learn to do this. It’s not rocket science, it’s habits of mind and habits of work. I started with people much more talented than me, and they’re dead or in jail or not writing. The difference between myself and them is that I’m writing.

–from “Annie Dillard and the Writing Life,” as recounted by Alexander Chee

Happy birthday, Annie Dillard!