Translated by Martin Aitken

On January 9, 1978, I was nine years old and living on a new housing estate in Tromøya outside Arendal in Norway. I’ve no idea what happened in my life on that particular day, nothing has stuck in my memory. But the records of the meteorological station at nearby Torungen Lighthouse tell me the weather was cloudy, the temperature six degrees Celsius, and that the wind picked up into a strong breeze between 1 and 7 p.m. School must have just started again after the Christmas holidays, meaning I’d probably have left the house about 8:15 that morning and walked up to the B-Max supermarket, where the school bus would have picked us up at 8:30. The trees would have been swaying in the wind, the spruce heavy and reluctant, the pine springy and more compliant; there can’t have been much snow on the ground, and the grass would have been yellowed.

Although by this time I’d started reading the local newspaper delivered to our mailbox every morning, and was therefore at least vaguely aware of what was going on in the world around me—I knew that the American president was called Jimmy Carter and that Norway’s prime minister was Odvar Nordli, and I’d heard of Indira Gandhi, Golda Meir, and Olof Palme—my reality was still primarily that of a child, so closely, closely bound to the things and people that were nearest to me.

The white tennis racquet I’d got for Christmas two weeks earlier, the name John Newcombe in blue cursive script on the shaft; the song of the strings when struck. The sensational taste of Muscat grapes. Dad’s red Opel Kadett, parked in the gravel drive outside the house. The pale face of Geir Prestbakmo, my friend from next door, and his characteristic tuft of hair. Yes, I think to myself now, forty years on, how reminiscent that childhood existence was of the life ascribed by Heidegger to animals, which he construed as being held captive by their surroundings and functions, as if they were spellbound. Not even the skylark sees the open, he wrote, by which presumably he meant that the animals know only the few stations of their day-to-day existence and how they relate to them. We can only guess at how close the life of a child actually comes to that of an animal in this respect, but having read what Ingmar Bergman wrote in his workbook that particular day, it’s tempting to think that my own experience, at least, was closer to the animals’ than that of the adults around me, for nothing of what Bergman was thinking and doing that day was in any way familiar to me then, nothing of what was important to him was important to me—we were living in totally distinct worlds.

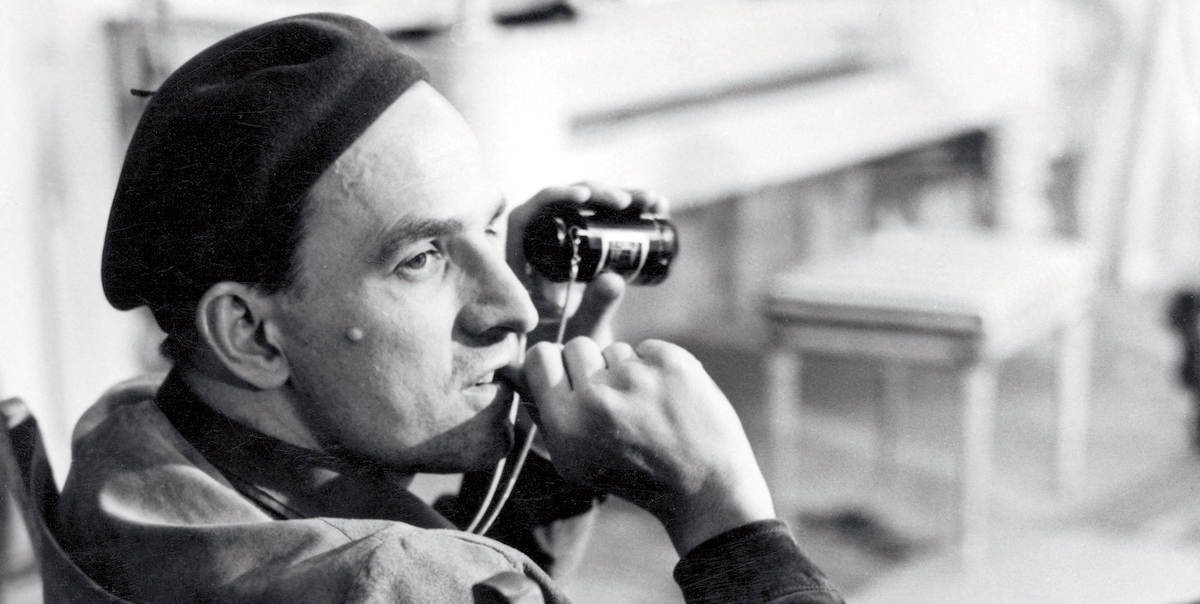

On January 9, 1978, Ingmar Bergman was at his office in Munich, where doubtless he had sat down at about the same time I got to school, for Bergman was a creature of habit, unsettlingly pedantic, beginning his daily writing session at nine and concluding it three hours later on the stroke of twelve, midsentence if need be, according to interviews with him, and so I assume his regimen applied on this day too.

Bergman was fifty-nine years old, with thirty-six films to his name, and now, on this particular morning, he was working on the script of another. His office was on the sixth floor, and from his workbook we can see that this was the first time he’d used it. He was dissatisfied with his pen—“this is a stupid pen”—but he liked the space and was optimistic about the project he was working on. “Something is beginning to take shape and crystallize. What it is, I don’t know,” he wrote.

Bergman was a creature of habit, unsettlingly pedantic, beginning his daily writing session at nine and concluding it three hours later on the stroke of twelve, midsentence if need be.

The script he was working on was called Love Without Lovers. It was never to be realized, the producers he collaborated with would end up rejecting it, but he knew nothing of this as he sat at his desk and scribbled away in his workbook, focusing himself fully on the script as he had done now for several months, and there was nothing in the way he applied himself to the work to suggest this would be a failure rather than another masterpiece. He was going about it the way he’d always done: first noting down ideas and conceptions, images and thoughts in the workbook, a sort of conversation he conducted with himself, embarking then on the script proper, a process he would often continue to comment on and discuss in the same workbook as he went along.

The workbook was in other words a kind of ladder leading from the writer to the work. Usually, the writer will take that ladder away once the work is done, allowing the work to stand alone, isolated as it were from its creative context. Bergman’s workbooks are the ladder left in place. Of course we might ask ourselves what value they have for posterity, being neither finished works in themselves, nor even parts of finished works, consisting simply of the mental debris and detritus of art. The workbooks are to the work what a shopping list is to an evening meal, or what the smears of paint on the artist’s palette are to a finished canvas, so isn’t their publication just another addition to a Bergman cult seeking to elevate and make relevant everything the master touched, even down to the last sweepings? And don’t we already have enough about how the films were created and about Bergman’s private life outside them? Can’t we just stick to the films? After all, it’s the films that continue to make the name of Bergman resonate for us.

It’s a valid point, certainly. But the value of the workbooks lies not so much in the emblematic Bergman name, the auteur’s running commentary on his own films, as it does in the opposite, or so it seems to me, because what they’re about is something underneath the name, outside its scope, representing and revealing to us creative processes in their own right. What does it mean to create? What does it take? How does an artist open up a creative field for a work, how do they keep it open, and how do they enlarge it? What do they consider, what do they look for? How do they ground their work in their own lives and at the same time make it relevant to others too?

One of the most important aspects of these workbooks is the remarkable sense of process they provide—not only are the projects they’re concerned with in process, the books themselves are process, and as such unworked. This contrasts with the completed works, as well as with the name that underwrites them. In order to create something, Bergman had to go sub-Bergman, to the place in the mind where no name exists, where nothing is as yet nailed down, where one thing can morph into another, where boundlessness prevails. The workbook is this place—in it, Bergman could put anything he wanted, the entries he made there could be completely inane, cringingly talentless, heartrendingly commonplace, intensely transgressive, jaw-droppingly dull, and this was in part their purpose: they had to be free of censorship, in particular self-censorship, which sought to lay down constraints on a process that needed to be wholly unconstrained. This is what he wrote himself about the functions of the workbook: “I can’t even be bothered to write them down in this workbook, which needs to be so unpresumptuous and undemanding and is intended to sustain like the mellowest woman almost any number of my peculiarities.”

The first prerequisite of creating something is to set up a requirement-free zone. This is what Bergman did with his workbooks. A second precondition is to be alert to every inner impulse, regardless of how unimportant it might seem. A good example of this might be lines that appear in the workbook on April 12, 1965, which read as follows:

Dejection and sorrow and tears passing into profound outbursts of joy. A sensitivity of hands. The broad forehead, severity, eyes that explore, the soft and childlike mouth. What is it that I want from this. Well, I want to start from the beginning. Not to contrive, not to incite, not to act up, but to start from the beginning on something new—if I have it in me.

What does it mean to create? What does it take? How does an artist open up a creative field for a work, how do they keep it open, and how do they enlarge it?

It’s not much of a starting point for a film, certainly nothing worthy of pitching to a producer. A pair of sensitive hands, a broad forehead, and a soft mouth. Nevertheless, this vague image was the seed of what was to become Persona, Bergman’s absolute masterpiece. It’s interesting to see, I think, how that film was conceived in something so tentative, so faltering, rather than in the idea of a woman who has stopped speaking, or the idea of two women’s identities merging together and becoming one. These ideas don’t appear at all until much later in the process, and in the workbook we can see where they come from—in the months leading up to the sensitive hands and the face with its broad forehead and soft mouth, Bergman writes often of how false he feels himself to be, how much fumbling and feigning his art contains, how the wish to please others impresses itself on everything he does.

The notion that truth is an inner quality corrupted by outer realities is one that cuts through everything Bergman writes and thinks, and the consequence of that notion is something he injects into the character behind those sensitive hands, the face with the broad forehead and the soft mouth, in the form of a single, striking characteristic: she has stopped speaking. It’s a stroke of filmic genius, and yet it wasn’t contrived, it emerged out of his own personal agonies and torments, as a result of something that occurred to him: if truth is inside me, yet everything I say is false, the only logical consequence is to stop speaking.

And with that, Bergman found himself bang in the middle of the third prerequisite for artistic creation, which is to discover the trigger point where one thing leads to another. Where one image gives rise to another image, one scene gives rise to another scene, one song gives rise to another song. To discover the point that is so packed with meaning or so alive with contrasts that it cannot be exhausted but continues to propagate new ideas. A woman who’s stopped talking represents just such a point. What if she meets another woman, a woman so naive and totally uncorrupted that she possesses not a note of falseness, what happens then? One situation propels the next, the women grow closer to each other, eventually their faces merge, a scene so striking and so iconic we think it surely must have been the very point from which the film issued. But it wasn’t, it was that vague image of a pair of sensitive hands.

In the formative work on these two characters, and indeed nearly all the characters in his workbooks, it’s sometimes hard to know who’s talking, whether it’s Bergman himself or Bergman in character. The space is wide open, boundless. The “I” of the workbook may be the real, biographical Bergman thinking out loud, or it may be Bergman projecting himself into the thoughts of someone else. The ability to establish such boundlessness of character was one of the most significant elements of Bergman’s talent, and perhaps the most mysterious, because as a human being in the world Bergman was an introvert, and not only that, he was also insensitive to others and could exhibit an almost pathological lack of empathy. He wrote this, for instance, in his workbook, dated July 4, 1976:

All day yesterday and tonight as well absorbed with the necessity of making this film. But whether artistic or practical reasons are dictating this need I don’t know. It’s important, that’s all. Nothing must get in the way. The only difficulty at the moment is of course uncertainty. Can this be done, is it really possible, reasonable and so on. Besides, I must get used to the situation. It’s rather important in fact. It feels so unusual to be sitting here at the desk putting words to paper.

I think it’s the form that worries me the most. I can’t find the form, it’s not coming to me on its own. Or rather it is, but I find it tedious and uninteresting. And I’ve no inclination to write it down like that. I wish I could just skip all the mediation, all the practical circumstances and transitional phases.

My little grandson Lukas, whom I didn’t know, drowned yesterday. He was only four years old.

A small bird, greenish gray in color, flew into my windowpane and broke its neck.

I sit in my tower and life goes on outside.

The film he’s worrying about is Autumn Sonata, and the incident he mentions almost in passing, his four-year-old grandson Lukas drowning the day before, is not only presented as a parenthesis in his life, but is later worked into the film, which has a small boy drowning too.

One of the most important aspects of Bergman’s workbooks is the remarkable sense of process they provide—not only are the projects they’re concerned with in process, the books themselves are process, and as such unworked.

“What is it that has made me an invalid at the emotional level?” Bergman wonders elsewhere in the workbooks, and while it’s unclear whether this issues from inside a character or from Bergman himself, there seems no doubt that he was driven by the question and moreover that it comprised another of those conflict-heavy, meaning-packed trigger points where still new images could be teased into being. And it is strange, is it not, that a person who was so excluding of others could be so open to them in his art? That in his art there were no boundaries between himself and others, whereas in life there was hardly anything but?

*

So the workbooks are where Bergman is boundless. But on January 9, 1978, they’re a dead end. Masterpieces lie behind him, and what lies in front of him is something he cannot pry open. He thinks he’s doing so, believing just as much in Love Without Lovers as he did in Persona, but to anyone reading his notes it seems clear that they’re driven by will alone, that the images, rather than coming from within, are steered by external factors. Love Without Lovers is West Germany, it’s terrorism, it’s violence, it’s sex, it’s coldness; it’s metacinema, and clever going on clever-clever. Such inventiveness came easily to him, his was an intelligence that meant that he could make films that weren’t anchored in his inner being, his own feelings and experiences, he’d done it before, many times.

He knew too what had to counterbalance it: “I think what’s needed is to undo every kind of commonsense logic, every conceivable chain of cause and effect and concentrate only on that which is feeling and feeling and feeling, then nothing of this will not be true and right.”

The workbooks are full of such notes to self, and those he wrote in 1963 resemble those he wrote in 1978 and 2001, concerned always with penetrating into the core, following his feelings, in order to get to that inner truth. Yet these reminders are rational, they belong to thought and have no access to those cognitive spaces where the creative act takes place, but can only point to them. Some eighteen months later, he reflects on that time, assessing it thus:

“How much I’ve done without conviction and on will alone during these last years. It can’t be good.”

*

On the whole, the workbooks follow interior processes, focusing mainly on the projects in which their writer was engaged at the time, meaning that the exterior world, its events and politics, are almost completely absent. During this period, 1977, 1978, 1979, Bergman’s life is largely embroiled in tax issues with the Swedish authorities, for which reason he exiled himself to Munich, and from the tone and character of what he writes there it’s evident that he’s depressed, that he’s lost his spark. There’s an air of compulsion about the writing, it’s something he forces himself to do, a salvager of identity: in spite of everything, he remains the great auteur.

The notion that truth is an inner quality corrupted by outer realities is one that cuts through everything Bergman writes and thinks.

This is how it looks from the inside, if we read the workbooks from those Munich years. But in the first months of 1978, Ingmar Bergman gave a major television interview for the South Bank Show, broadcast to coincide with his sixtieth birthday that summer. He was interviewed by Melvyn Bragg in a small room in Munich, presumably the same room in which he wrote. This was a Bergman full of vigor, vital and generous, a stark contrast to the impression he gives in his workbook at the time. Perhaps it’s because this was an opportunity to talk about what he’d already done, the completed works, whose agonies and emotional costs were forgotten, a few hours in which he could step into the role of the great auteur and forget the strained and failing scriptwriter in exile who didn’t know what the future would bring.

Bergman makes lavish use of the word “magical” in that interview as he explains the nature of film. In one example he starts talking about a chair, the way film can turn a quite ordinary chair into the most fantastic and precious chair the world has ever seen, studded with diamonds and jewels, simply by someone saying so. The magic consists in the belief. His eyes sparkle as he speaks of it. What he’s on to here, as I see it, is the child’s intrinsic fascination, and the capacity of film to cast a spell.

Nine months later, the following appears in his workbook:

I think I know what film I want to make next and it’s certainly very different from anything I’ve done before. I see it as yet very dimly and unclearly: Anton is eleven years old and Maria is twelve. They’re not brother and sister as such, but something like it. Half siblings, perhaps. They’re my observation posts, looking out at the reality I want to depict. We’re at the turn of the century or something like that. The beginning of the First World War perhaps—that might be right. The place is a small town, very quiet and well kept. There might be a university there. Or is it the end of the war? I don’t know. But all threat is remote. Life is quiet and peaceful. Maria and Anton’s mother is the director of a theater. Their father has died and she has taken over and runs the theater with authority and shrewdness.

This of course is Fanny and Alexander in its first, tentative beginnings. When it was shown for the first time three years later, the most fantastic chair the world had ever seen appeared in one of its scenes. It takes place in the nursery on Christmas Eve. The children’s father, the soon-to-be-deceased theater manager Oscar Ekdahl, enters and pulls out the chair, lifts it up and places it in the light. This isn’t just any old chair, he says. It may look like an ordinary nursery chair, humble and rather battered, but you can’t go on appearances, for this is the most valuable chair in the world. It belongs to the emperor of China.

The children are spellbound, their eyes sparkle as they gaze. The older ones suspect they’re being deceived, yet hang on their father’s words. The chair, illuminated in the darkness, is more than three thousand years old, he tells them, made of a metal that is only to be found deep inside the earth, more precious than diamonds. It was a birthday present for the empress who would sit on it and be carried about wherever she went, and when she was buried she was sitting on it too.

The father disappears for a moment. When he returns it’s in the guise of an old wife who derides the chair for its battered appearance, he pretends it bites her on the behind, and just as she’s about to give it what for, Fanny shrieks at him to stop at once, for the chair belongs to the empress of China. It’s such a moving moment in the film, for some reason it never ceases to make me cry, Fanny having believed every word of her father’s story, and when he realizes this he looks at her with the tenderest, most loving eyes.

On the whole, the workbooks follow interior processes, focusing mainly on the projects in which their writer was engaged at the time, meaning that the exterior world, its events and politics, are almost completely absent.

Why is it so moving?

Perhaps it’s the vulnerability that lies in innocence, or simply the very presence of innocence itself, uncalculating and uncynical, the uncorrupted heart of the child who believes what she sees and hears, for whom remoteness does not exist, who knows no outwardness, in whose world everything is heartfelt.

Not until many years later did it strike me that Bergman had made me believe his story of what took place in the nursery in the same way as the father in the film made his young daughter believe his story about the chair.

*

Fanny and Alexander was my first encounter with Ingmar Bergman. I was a teenager then, and I enjoyed the film and was entertained by it, but I wasn’t moved, at least not in the way I was moved by Agnar Mykle’s novel Lasso Around the Moon for instance, also in my teenage years. And when at twenty-something I saw my second Bergman film, Wild Strawberries, I thought it was good, intensifying with the angry, arguing couple picked up in the car, but not a film that actually meant anything to me. What was such a small and flickering flame compared to the great blazes that raged in the novels of Dostoevsky? And the famous dream sequence at the beginning, the clock with no hands and the coffin that falls off the hearse, has something too spelled out, almost primitive about it, as opposed to the works of writers like Bruno Schulz or Franz Kafka, where the blending together of the desolate and the unreal condenses in ways that are similar. And what is the scene in which the professor physically wanders into his childhood memories compared to the way Proust deals with reminiscence in In Search of Lost Time?

Comparing great novels with great films in this way always feels like something of a disservice to the films, for they fall short. But this has nothing to do with their makers, film is simply the lesser medium.

There’s no reason we can’t be honest about that.

Or am I the only one more receptive to literature’s internalization of reality than to film’s externalization of our internal lives?

Whatever, it wasn’t until I read The Best Intentions that a work of Ingmar Bergman moved me. More than that, The Best Intentions changed the way I understood myself and my own family, in particular my father. And it became important to my own writing. So important in fact that I named the main character in my first novel Henrik and included, following the pattern of Bergman’s book, two hundred pages about how his parents had met.

Since then I’ve read The Best Intentions and its successor Private Confessions several times, most recently only a few weeks ago, and I have to say that no literary work of that time outshines them.

Why are they so good?

Comparing great novels with great films in this way always feels like something of a disservice to the films, for they fall short.

What’s striking about them is the emotional precision Bergman achieves, not only in each of his characters but also in the interactions between them, where so many conflicting forces collide, unrelentingly propelling the story forward. Bergman’s masterly skill lies in his ability to bring out every perspective, imbuing in the reader the sense that each character is as important as the next, at the same time making it plain that the sum of these perspectives can have but one inevitable conclusion. Both books are fictionalized accounts of the lives of his parents—The Best Intentions deals with their first encounter, their falling in love and embarking upon a life together, while Private Confessions depicts the way that life fell apart, viewed through the story of his mother’s infidelity. The maternal grandmother sees from the start which way things are heading and tries to intervene, though unsuccessfully. Henrik, the father, is a fantastic literary character, racked with feelings of inferiority, shame, ambition, and confusion, at the same time as he is pure of heart and guileless. The grandmother likes him, but understands the threat he poses, though her insight is to no avail: what has to happen, happens.

This determinism is of course far from absolute; the father and the mother are free individuals, the decisions they make are by no means inevitable, and surely they would have chosen differently if only they’d known better, and yet they act as they do. Nor does the determinist element here come across as formulaic, the way it does in crime novels for instance, where a standard pattern begets standard events, which in turn substantiate the pattern. In Bergman’s two books the opposite is true: the event implies the pattern, meaning that the pattern in a way comes toward us, as if for the first time, with the particular force perception lends to insight. Yes, life is determined! Yes, our character predestines what will happen to us! It’s true.

The truth of the two books, the truth of the mother, the father, and the things that happened between and beyond them, has nothing to do with whether the mother and the father were like that in real life, or whether the events depicted actually took place in that way. Truth is based on experience and exists within us, founded on something so imprecise and vague as feelings. Thus, the portrait of Bergman’s father, Henrik, could just as well be a portrait of my own father—or rather, the portrait of Bergman’s father gave me insight into my own father, who was also alive on that January day in 1978, a thirty-four-year-old teacher who probably didn’t relate that closely to Bergman, but still knew who he was, of course, not least after having watched the TV series Scenes from a Marriage with my mother a few years before.

As I read The Best Intentions again, it’s not so much my father as myself I see, if not in the details, then in the way the unperceived impacts on the perceived, working away at our blind spots, the areas inside us that we can’t see. These are the remnants of the child, relics of our childhood world, lingering in the adult, for the child does not know itself from the outside, only from the inside, and for Bergman, who in everything, absolutely everything he wrote, was looking for relationships, art was the place where the child’s one-to-one relationship with the world could be both reestablished and brought into view. This is the dynamic of Persona, of Fanny and Alexander, of The Best Intentions. And in the workbooks his game is always: I see a pair of hands, I see a face, and when I say they exist, they exist. That truth was what allowed Bergman to begin his autobiography, The Magic Lantern, with a sentence that was factually incorrect. The lack of any essential difference between what happened and what could have happened is another form of boundlessness that characterized Bergman, nowhere more visible than in the workbooks, the ladder he climbed and descended almost every day, which ran from his life to his art.

__________________________________

From In the Land of the Cyclops by Karl Ove Knausgaard, trans. Martin Aitken. Used with the permission of Archipelago Books.