How To Proceed is a bi-monthly conversation about writing, creativity and the world we live in. Author Linn Ullmann talks to some of the world’s most exciting literary voices about their books, their writing process, and how they view the world and current events around them.

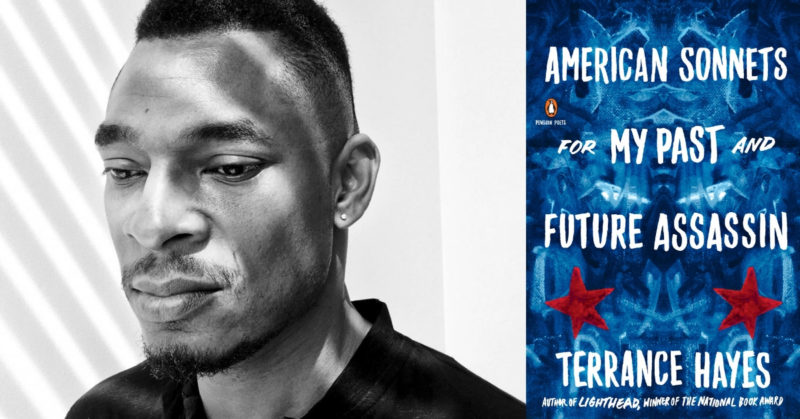

On today’s podcast, Linn Ullmann talks to Terrance Hayes, author of American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, about the myriad ways he approaches form, how Trump uses language, and whether the system needs to be burned down or a piece of history preserved.

From the conversation:

Linn: I want to follow up on what you said about starting to write these sonnets after Trump was elected with Ali Smith’s question to you. Because that’s what we do on the podcast How to Proceed; every author that I talk to has a question for the next author, to create a kind of conversation. And here it is, Ali Smith says: “First of all, I want to thank him for American Sonnets, because what a book! Thank him for knowing that we have to break form apart by using form. Fantastic. But my question for him is: in a standoff between Trump and poetry, what happens?”

Terrance: I can probably answer that question by also thanking her for all the observations about the book. I am trying to see if you can break free inside of a form. If the form is like this white patriarchy, white male intellectual creative palace, the kind of intellect that gives us democracy and all that kind of stuff, and if you find yourself in your body, a Black man, whose descendants were enslaved by these intellectuals, how do you manage that system? Do you destroy that system? Do you just burn it all the way down to the ground? These days I think that’s what people think are the options. I don’t think that. Or do you figure out how to function within that? How do I get things to bend in order to change them versus shattering them, where possible. Or is it like a windowpane? If we break all the glass and leave one shard, is that enough to give people a sense of what that history is?

I say all that to say that my engaging with the sonnet is trying to see if you can get free inside of a system that didn’t think about you when it was made. Or didn’t think about Black people writing sonnets when people were writing sonnets. That answer comes back to the question of Trump versus poetry. I would say you’ve got to ask about time, how much time do we have here? Ultimately poetry wins out. But how long is it going to take before it wins out? The way that it wins out is so much more quiet and more intimate in a way than what Trump thinks language is for.

But in the short term, it looks like someone who has a clear disregard for language—which is to say that poetry, language, can do something. It seems like that kind of knuckleheadedness, weaponizing the language, seems like it’s super powerful. If you know what gaslighting is, everybody who’s been in a relationship knows what the notion of gaslighting is. That is essentially what it seems like in the media term. They’re trying to convince you that when you say a word like love, that’s not what you mean. Again, that’s gaslighting. That’s someone using language and then saying “what I said is not what I said.” In the short term it seems like that’s winning out, but it’s not.

Poetry wins out. Because poetry asks you to trust some combination of head and guts. Mind, body, soul. I think it’s one of those places there are so many overlaps. Reading between the lines, but also reading the lines themselves. Poetry rewards that kind of thinking. It does win out, but it doesn’t win out in the same kind of glamorous, bombastic, and ultimately violent way that Trump is wielding language right now.

Linn: You talked about form, and Ali talked about form also. I want to ask you about form, because you’ve always been experimenting with form and playing with form, seeking refuge in form. A big part of form is constraints. You are a writer, a poet, who obviously imposes constraints on yourself. Can you tell me about why you actively seek constraints?

Terrance: It’s an interesting question. I have all these categories for my views of the world. The metaphor for my notion of constraint would be that every country has different speed laws. Here in America, I feel like if I’m doing ten miles over the speed limit—I don’t know how that converts to meters—you’re just barely breaking the law. A cop told me this one time: if you do fifteen miles over the speed limit, they’ll stop you. But ten is almost not worth it. The penalty for that is not quite worth it. That’s the area I like. The area where the cop sort of has to make a decision based on context versus a decision based on law.

And even driving the car, you’re making a decision. Sometimes there’s nobody else on the road, I think I’m going to do ten over the speed limit. Maybe I’ll go a little faster in this context. That is how I think about form. It’s how I think about how people relate to each other. It’s contextual. Let’s see what the moment looks like, versus general rules. In a philosophical sense, I think we know that’s true anyway. You don’t kill people, but we have wars. These kinds of questions. It seems like the way the world works is in fact by looking at the particulars of things versus the general observations around things. That reverberates in all kinds of ways. That is my interest in form.

***

Litteraturhuset in Oslo is Europe’s largest of its kind, dedicated to presenting literature in the broadest sense of the word. Since its opening in the fall of 2007, the house has welcomed authors from all parts of the world, and through readings, conversations, lectures and debates, it strives to open up for new horizons and perspectives on the society, the world and the people around us.

Terrance Hayes is the author of Lighthead, winner of the 2010 National Book Award and finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. His other books are Wind In a Box, Hip Logic, and Muscular Music. His honors include a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a 2014 MacArthur Fellowship. How To Be Drawn, his most recent collection of poems, was a finalist for the 2015 National Book Award and received the 2016 NAACP Image Award for Poetry.