As the election nears and House Democrats continue to spar with USPS Postmaster General Louis Dejoy, one could be forgiven for feeling anxious about the mail.

On Monday, the UCLA Voting Rights Project published a report on the need to build trust among Americans in the vote-by-mail process. Although the president’s stance against mail-in ballots might seem to suggest otherwise, the issues the Postal Service has faced this summer aren’t solely the result of recent efforts to restructure the agency.

Still, many Americans—including this one—weren’t soothed by the Postal System’s assurance that they’ll be able to process large volumes of ballots. That’s nice, but one of the more alarming aspects of the mail controversy is the way in which the current administration has politicized a normally beloved arm of the government.

Fears that disinformation, disenfranchisement, and voter mistrust will severely impact voter turnout are not without justification. To be clear, 2020 is not the first time racists have cast doubt on the federal postal system in an attempt to maintain power.

Nearly 200 years ago, in the summer of 1835, northern abolitionists organized a massive effort to flood the country with anti-slavery literature. This included the more than 100,000 newspapers and political tracts that were sent to the South. Historian Jennifer Rose Mercieca, writing of the 1835 abolitionist campaign, notes that many landowning elites in the region interpreted the campaign as an attack on their community norms (read: slavery).

Slaveholders called the mail inflammatory, incendiary, and insurrectionary. One of the most notable incidents in response to the influx of abolitionist literature took place in Charleston, South Carolina.

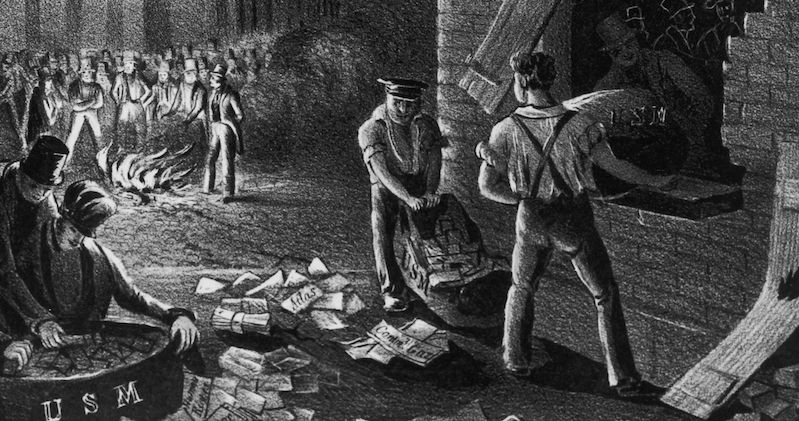

On the night of July 29th, 1835, a vigilance society known as the Lynch Men broke into the town’s post office, identified the mail from the American Anti-Slavery Society and, the next night, burned the literature and effigies of prominent abolitionists in a lurid bonfire. Hundreds of onlookers were said to have gathered.

How was this allowed to happen so publicly? It helped that Postmaster General Amos Kendall had advised the postmaster of Charleston to suppress the abolitionist tracts. In fact, the havoc some white southerners unleashed on the streets was mirrored in the actions of certain postmasters and even shipyard workers, who sometimes spotted and summarily destroyed the northern “contagion” in their cargo.

South Carolina was one of four southern states that outlawed the abolitionist writings in their jurisdictions. Slaveholders tended to justify such reactions by appealing to patriotic service at the expense of law. Some accused the postal system of supporting abolitionist endeavors.

One newspaper, the Charleston Southern Patriot, declared that if white people saw fit to take action: “Let it be performed in open day light and on the highway, and that persons of responsibility and weight of character be deputed to act in the name and for the good of the whole of the citizens.”

The abolitionist campaign is often considered one of the events that reignited interest in the slavery question down South, which had been terrified by the rebellion Nat Turner led in 1831. Multiple rumors of planned slave revolts circulated in 1835.

Rose Mercieca observes that the universalization of white male suffrage in the 1820s increased the number of non-slaveholding whites who could potentially weaken the political influence of slaveholders. This irony, egalitarianism as the unwinding of elitist influence, might also have influenced the attack on the mail. The postal system itself, rather than non-slaveholding white people, became the scapegoat for anti-slavery opposition.

Whenever the current president inaccurately claims that universal mail-in voting favors Democratic candidates, spreads unfounded fears of voter fraud (thanks, Russia), or finds another way to question the integrity of the US postal system, he is using an effective, centuries-old tactic. In times of social unrest in the US, enablers of white supremacy have been terrified by the power of the mail and so tried to discount it.

In 1835, white supremacists feared the information Black people might be receiving. One-hundred eighty-five years later, the supremacists fear the ballots they are in all likelihood sending.