In the beginning was sex. And sex begat skill, and skill (or its absence) begat judgement, and judgement begat insecurity, and insecurity begat doctors’ visits, which begat treatments, which have flourished into a multibillion-dollar industry, so that sex between men and women is today almost inconceivable without the shadow of disorder, dysfunction, the “little blue pill” or myriad other medical interventions designed to bring sex back to some longed-for beginning again: a state of confirmed healthfulness, the illusion of normal.

Sex has been missing from the health care debate. A shame, because sexual health and disputes over its meaning reveal most nakedly the problem at the core of a medical system that requires profit, huge profit, hence sickness, or people who can come to believe they are sick or deformed or lacking and therefore in need of a pill, a procedure or device. Case in point: female sexual dysfunction (FSD), said now to afflict great numbers of women—43 percent according to some, 70 percent according to others, an “epidemic” in the heterosexual bedroom according to Oprah. Ca-ching!

More on that in a moment, but first a bit about FSD’s precursor, hysteria, and the rustic science of bringing women off.

In my room is an artifact of late 19th-century medicine, a heavy wooden captain’s chair with a difference: from below the seat, a cast-iron lever extends up alongside each arm, within easy grasp of the sitter. Work the levers forward and back, and powerful springs activate a mechanism to rock or jolt the sitter (depending on the vigor of the thrust) in a manner meant to produce the healthful effects of horseback riding for ladies suffering from fatigue, insufficient exercise and “pelvic congestion.”

This particular jolting chair was found in Chester, Vermont, by an antiques-dealer friend called Gilbert Ruff, but its provenance as an invention is said to reach back to a fabled arena of psychosexual medicine, the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, and to Jean-Martin Charcot, teacher of Freud and father of modern neurology. Charcot was an enthusiast for the idea that women with a grab bag of complaints, from irritability to sleeplessness to sexual fantasies and ungratified desire, were diseased. Hysteroneurasthenic disorder was the name for their sickness then. For some, he prescribed long train trips over rough trackbeds. If they took another doctor’s advice and leaned forward in the rail carriage, they might have got surprising relief. Such journeys were impractical, though, so a more homely vibration therapy emerged.

Today the cultural air is thick with sex, but the rhetoric of freedom largely serves a commodified notion of sexual performance.

Various iterations of the jolting chair entered commercial self-help markets. Mine was manufactured in New York, and advertisements promoted it to strengthen “the parts that are usually most neglected by the fair beings.” Now a woman might enjoy the chair’s humpy bounce in a room of her own, varying the intensity, parting her legs, leaning forward and breathing deep, even calibrating her motions to the rhythms of a French dance tune, or gavotte, written for the purpose. The jolt never proved as efficient, though, at achieving the “hysterical paroxysm” or otherwise-named form of relief that doctors or midwives had been inducing since at least the time of Galen simply with their fingers. The jolting chair was soon consigned to the curio attic, outperformed by pulsing water cures and that ultimate women’s aid, the vibrator, also invented by a doctor, who advised that, although his Manipulator could be beneficial in relieving pelvic congestion, those supervising its use ought to guard against women’s “overindulgence.”

As Rachel Maines argues in her delightful book The Technology of Orgasm, making patients out of sexually unsatisfied women was good business. The afflicted would neither die nor be cured but required regular treatments, weekly, sometimes daily, for an hour or even three. By one 1863 estimate, she writes, massage therapies accounted for three-quarters of some physicians’ business. Diddling women was work—“the job nobody wanted,” she says—abstracted from sex (i.e., robust progression from male hard-on to vaginal penetration to male orgasm) and requiring time and skill. With the vibrator, Maines hypothesizes, doctors’ productivity soared, as sixty-minute visits shrank to ten or five, raising more revenue from more patients, until the device became so technologically refined, popular and multipurpose (Sears marketed a home vibrator with attachments for beating eggs, churning butter, operating a fan) that the medical profession had worked itself out of a job. Miraculously the sick had been healed by the time the first vibrator popped up in porno in the 1920s.

Some sexologists and historians have blasted Maines for advancing an idea for which the evidence is patchy, debatable, unclear or nonexistent. Her footnotes have been challenged, along with her use of antique medical sources, her understanding of 19th-century medical attitudes toward female sexuality and her interpretation of evidence. Iwan Rhys Morus, author of Shocking Bodies: Life, Death and Electricity in Victorian England, tells me, “I can safely say that I have come across nothing in my researches on late 19th-century electricity and the body that lends any support at all to Maines’ argument.” Maines concedes that a lot of conjecture goes into creating a narrative from patent language, doctors’ statements, manufacturers’ marketing plans and fragments in medical texts where women’s orgasm is de-eroticized, or “socially camouflaged,” as she puts it.

The liberationist politics has dropped out, and without politics we’re all just patients, or potential patients.

Something did happen on the way from the doctor’s lab to the home. Leap across the decades, and that trajectory is positively progressive in that, willy-nilly, medicalization marched toward putting sexuality into women’s hands, into their heads in terms of body knowledge, and into the mix of culture, personal relations and a polymorphous physicality beyond biological function alone. The white coats came out again with Masters and Johnson but bumped into a counterculture that pushed against their categorizations of normal or not. Every 1970s woman might not have attended one of Betty Dodson’s masturbation workshops; every man was hardly reborn as an attentive, exploring lover. But nor was everyone straight, in all senses of the word, and the fluidity of sexuality as part of the great mishmash of human experience was out in the culture. It was sexual and also political. Today the cultural air is thick with sex, but the rhetoric of freedom largely serves a commodified notion of sexual performance. The liberationist politics has dropped out, and without politics we’re all just patients, or potential patients.

How else to explain that a reality as old as God—that the vast majority of women do not climax simply through intercourse—has re-emerged as dysfunction? Or that another grab bag of indicators of dissatisfaction and low desire is renamed hypoactive sexual desire disorder, for which a female Viagra or a testosterone patch or cream or nasal spray must be developed? How to explain that middle-aged women go under the knife for vaginal rejuvenation (basically pussy tightening) and that young women go under the knife for laser labiaplasty (basically genital mutilation), saying that they want only to feel pretty, normal, and to raise their chances of orgasm through intercourse? How to explain that a doctor like Stuart Meloy of North Carolina has even one patient to test his Orgasmatron, an electrode threaded up a woman’s spinal cord and controlled by a hand-held button that, Meloy promises, can make her clit throb with excitement during intercourse so as to reach the grail of mutually assured orgasm?

A terrific documentary by Liz Canner, Orgasm Inc., addresses those questions in terms of corporate medicine and the creation of need via pseudo-feminist incitements to full sexual mastery, as expressed by Dr. Laura Berman and other shills for the drug industry. Female sexual dysfunction, it turns out, was wholly created by drug companies hoping to make even bigger money off women than they have off men in the comparatively smaller market for erectile dysfunction drugs. That’s capitalism; that’s its nature. The more obstinate question is why so many people are willing to be its slaves, and whether a resistant politics can grow up to say not just “We want in” to health care but “We want out” of the profit system and, on the sex front, out of a medical model that elevates a doctor over “playing doctor” or a more sensual ease with oneself and others.

“So many times I don’t think sex is a matter of health,” Dr. Leonore Tiefer told me the other day. She is a sex therapist and founder of the New View Campaign to challenge the medicalization of sex. “I think it’s more like dancing or cooking. Yes, you do it with your body. You dance with your body too. That doesn’t mean there’s a department of dance in the medical school. You don’t go to the doctor to learn to dance. And in dancing school the waltz class is no more normal than the samba class.” You might not be a good dancer by some scale of values. You might not get the steps right, or do steps at all. But even in wheelchairs people learn to move to the music.

__________________________________

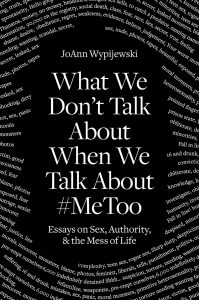

From What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About #MeToo: Essays on Sex, Authority and the Mess of Life by JoAnn Wypijewski. A version of this piece previously appeared in two columns in The Nation under Wypijewski’s column, “Carnal Knowledge.” Used with permission of the publisher, Verso Books. Copyright © 2020 by JoAnn Wypijewski.