My first encounter with nicotine was during my sophomore year of high-school. A fourth-liner on my varsity hockey team, I did what I could to fit in—and get some ice time. The seniors all dipped; they’d stuff it into their mouth until their lip looked puffy, using dip as a mouthpiece to pacify the ref should they ask them to prove they had protection in. Oftentimes a bulge was enough to get them to give you the okay.

Minutes into putting my fair share in, my coach tapped me on the shoulder. Up by a few goals, I think, he figured I couldn’t do enough harm to blow our lead. Seconds into my shift, though, I took a hit hard enough to knock the wind out of me and the ball of dip in my lip down my gullet. I got back to the bench and threw it back up through the cutouts of my protective cage. I never dipped again. Still haven’t, and that was more than 14 years ago.

My next encounter with nicotine didn’t come until senior year of high-school, when we ceremoniously smoked Cheyenne brand cigarillos to celebrate graduating. I tried my first cigarette last summer during a trip to London with a friend and his girlfriend. Months from turning 30, the rush of dipping into a shady convenience store, liaising with the clerk, converting our currency, and emerging with an infamously ominous pack of European cigarettes took us back. Childish? Sure. But we’re late bloomers, at least in terms of nicotine consumption.

You see, I’m old enough to have graduated high-school before Juuls came out. And long before the oddly-shaped ELFBAR ever dropped. Back then, we had Black and Milds; Backwoods; Dutch Masters; Swisher Sweets; and every cigarette brand CVS or 7-11 had to offer. There were plenty of snuff brands, too, but that never stuck at my school; except for with the hockey kids, but once I’d swallowed the stuff, I never got the urge to try it again. Simply put, this stuff sucked.

Nowadays, of-age nicotine consumers have options—significantly healthier ones, too, if one can fathom that. Take ZYN, for example, the Swedish brand of flavored nicotine pouches in tidy circular plastic containers introduced in 2014. Available in several flavors—from various mints and cinnamon to coffee and “vibes” like Chill and Smooth—it comes in two strengths (3mg and 6mg) and two quantities (15 or 20 pouches). The product presents users with a way to get their buzz without spit or smoke. Discreet, convenient and devastatingly addictive. Pretty ideal, right?

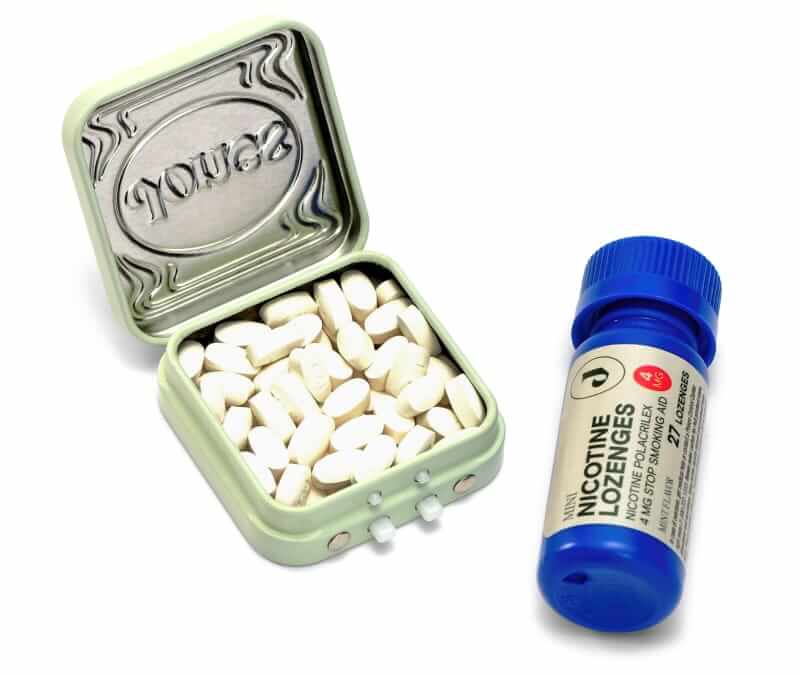

ZYN’s parent company, Philip Morris International, thinks so. In the first three months of 2024, sales were up over 80%. Cigarette sales, on the other hand, were down over 10%. And while concern over whether these products cater and are marketed to children remains constant, adult use, at least of nicotine pouches, is relatively ubiquitous and raises far less concern than in generations prior. And it’s not just pouches. There’s a bit of a nicotine boom happening at the moment. Just look at the stylish options from brands like Lucy, co-founded by the same guy behind Soylent. Or Rogue, which like Lucy, offers both pouches and more traditional nicotine gum as part of its “nicotine on-demand” products. Or there’s Blip and Jones, which offer lozenges as a more modern alternative to the more mundane practice of nicotine replacement therapy (which is approved by the Food and Drug Administration).

Let’s be clear, though. They’re still bad for you; just less so, especially since nicotine itself is not considered a carcinogen. In fact, researchers have been charmed by the compound’s potential benefits for decades.

“It probably has a small, but real effect on your cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Jonathan Foulds told the New York Times. He added that they’re a much better option than cigarettes, so long as someone doesn’t eventually step up from pouches to cigarettes (or vapes for that matter). This is certainly a risk, especially since roughly 66% of those that try a single cigarette become daily smokers. There’s a growing camp, though, that’s less worried about long-term use; in fact, they’re curious about what nicotine could unlock for them. Enter the biohackers.

Huberman Lab head honcho Andrew Huberman, Ph.D., said this during a recent podcast appearance: “Nicotine is an amazing nootropic, but the delivery device will kill you. Smoking is not good for you; vaping is not good for you; dipping is not good for you; snuffing is not good for you.” On his own, he doubled down, echoing his earlier sentiment. “Nicotine triggers the release of dopamine from the nucleus accumbens. This is what gives nicotine its rewarding properties. It increases motivation, it tends to give a not so subtle, but very transient, feelings of wellbeing and alertness.”

This combination is helping these smokeless nicotine products catch on with office workers and optimizers. “It’s almost become ubiquitous with juniors in the finance industry,” Mark Moran, CEO of the investor relations firm Equity Animal, told Bloomberg. “You’re working long hours, you’re bored. It’s discreet enough that you could have a Zyn in a client meeting. You could be talking to a partner. It’s culturally accepted in finance.”

That’s true at the bottom and the way, way top: Peter Thiel, worth $6.7 billion, said in an interview with The Atlantic that nicotine is a “really good nootropic drug that raises your IQ 10 points.” Bold statement, Peter, especially since IQ score is rarely immediately quantifiable. Your heart rate is, though, and nicotine surely raises it. Nicotine has other long-lasting potential effects, too, like cardiovascular problems and mood disorders. But Thiel’s humor-led stance on nicotine is not unique—in fact, it’s an ever-popular one shared by equally online, often right-wing, personalities like Tucker Carlson. (“I use it every second I’m awake,” he said in 2023.)

It’s true that almost anything is okay in moderation, but lumping nicotine products in with new-age health-minded goods (like AG1, for example) advertised on podcasts like Huberman’s is a slippery slope—and if you’re popping a ZYN mid-meeting to outperform your colleagues, you’re probably already halfway down it.