This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Article continues after advertisement

There comes a time each winter, after the cold settles into the rafters and my streaming services exhaust themselves in a digitized blur, that I find myself drawn to art museums. I want to walk among their gaudy poinsettias and turtlenecked patrons. I want to make self-satisfied comments about chiaroscuro and form.

I’m not alone in this migration. Countless others, herded through ticketed entry times, will join me. Here I recognize the marks of my species: eccentric eyewear and improbable scarf knots, performative opinions about Warhol, Monet, or Van Gogh. We draw strength from our familiar surroundings. We move, as if by instinct, from coat check to artwork to gift shop to street.

Still, there’s something predatory in my attendance. I finger the pencil and notebook—ok, it’s a Moleskin—stowed in my pocket. I linger at a painting, jotting down a few lines. I’m hunting for art with which to make poems.

If you’ve ever taken a creative writing class, this act will be familiar. You probably walked, at least once, from classroom to campus gallery, shepherded by a professor too cynical, underpaid, or hungover to manage a more robust lesson for the day. Maybe you received a note on ekphrasis—loosely defined as literary art made from visual art—before reading W.H. Auden’s “Musée des Beaux Arts.” Then you were released to seek inspiration on the walls.

I am here to tell you that I’ve found exactly that, despite this exercise’s predictable outcomes: a meditation on a Dutch fruit bowl, a sad lyric about a sad Edward Hopper. This often happens between semesters, when I’m coaxing my own poems out of hibernation. It happens when I’ve been perfectly satisfied to wander and look. The question is why?

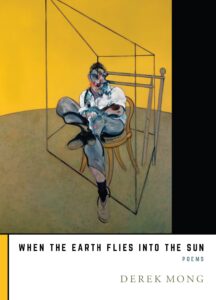

In my latest collection, When the Earth Flies into the Sun, museums mid-wived a handful of short poems and one long one; they offer some answers. For starters, it’s easier to start a poem from a painting, sculpture, or photo. The blank page looks less blank when an image lingers, like a ghostly pentimento, beneath the paper’s whorl. The first lines I write, then, are inevitably descriptive, an attempt to whisper that image up to the surface.

This language tries to render the visual into the verbal, to plop the reader down—like the noodle-armed avatar of Google Maps—before the artwork itself. It’s there in “Partially Restored Statue of a Silver Bull,” my poem about a reassembled offering to the Delphic Oracle. It’s still present in the poem’s first lines:

Like cattle shrapnelled__________or beef tips in tinfoil

you don’t cohere___________into a steer

till our eyes (blink, blink) rebuild you.

Appositional similes and imagistic flourishes, half rhymes tripping over true ones: I’d write like this until the ancient cows come home. Or, as Elizabeth Bishop writes of her own ekphrasis, until everything is finally “connected by ‘and’ and ‘and’” (“Over 2,000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance”). But a poem must be more than description, lest it try (and fail) to beat art at its own game.

Ekphrasis excites me because of the paths it suggests beyond pretty language. I like how it can marry art criticism with creative writing. I like how it can beam us, Trek-like, to the colorful planets of our past. And I like the rhetorical modes that it historically favors. These are modes born of visual art’s presumed silence and poets’ inability to leave silence alone. In this we’re like disc jockeys. Or leaf blowers. Or insecure dogs.

I’m thinking here of dramatic monologues and direct address. The former animates some of my favorite contemporary ekphrastic poems: Natasha Trethewey’s Bellocq’s Ophelia and Paisley Rekdal’s “Shooting the Skulls: Devotionals” In both works, the visual subject matter—sex workers in New Orleans and human skulls in Colorado, respectively—talk to the reader. That move concludes John Keats’s famous ekphrastic poem too: “Ode on a Grecian Urn.”

Direct address, I imagine, is equally common, born of a perceived intimacy between poet and personified art. Think of a comic drunkard confiding, late at night, in a statue. Think of religious icons that compel one to pray. Or think of John Ashbery’s “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror,” a poem he addresses to a painter, Francesco Parmigianino. Helen Vendler refers to Parmigianino as Ashbery’s “invisible listener.” I love that term, which I recognize in my ekphrasis too.

Here is the world, delivered piecemeal in so many multi-sized frames. And here are you, sorting out your place in it, one long stare at a time.

In my time, I’ve addressed Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man and a Greek god, Asklepios, that “[b]as-relief beefcake” whose serpents and staff remind us he’s a healer. (“My insurance card / sends its regards.”) I’ve apologized to Aphaea, a minor mythological figure and #MeToo victim, for the awful acts of men. And I’ve spent 160 lines talking to (and about) the British painter, Lucian Freud, who looks out from Francis Bacon’s “Three Studies of Lucian Freud.” That painting serves as the cover of my new book.

The poem itself, “A Poem for the Scoundrel Lucian Freud,” began one winter afternoon when, while visiting the Portland Art Museum with my wife and son, I saw in Bacon’s violent portraits the violence that made our family. “[R]ed of rare steak, gray like smudged lace,” I’d go on to write, comparing Freud’s face to what played out improbably in my mind: my wife’s C-section, our son’s birth. A quick glance at Lucian Freud’s own life and work—40 unacknowledged kids; lush, sexualized portraits—and I knew I had a project.

This is what I love most about ekphrasis; it foregrounds a response to art that seminars and lecture halls eschew: the affective, the personal. It’s also the response that I’m likeliest to have when granted a few hours to ruminate, remember, and write. This is a welcome shift from ekphrasis’s origins in classical rhetoric; Cicero would’ve used it to memorize a case. The “points of an argument,” as G. Gabrielle Starr explains in the Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry & Poetics, could be placed in a “mental image—the 12 houses of the zodiac, imagined in a wheel.” Ekphrasis helped Senators stay on track. Today it’s likelier to roam.

Which is another reason that an art museum fosters ekphrasis. Its space isn’t just a secular church or visual repository. Like its sibling, the public library, the art museum is among the last redoubts of dawdling contemplation in a culture consumed by efficiency and speed. Sure, you’ll spot a boomer in a preposterous beret. You’ll pay $8 for a muffin. These are small drawbacks, though, compared to all that you’ll encounter.

Here is the world, delivered piecemeal in so many multi-sized frames. And here are you, sorting out your place in it, one long stare at a time. Something will enrage you and something will haunt you. Something will remind you of all the mistakes that you’ve made in the long haul of your life. And something will strike you as beautiful and true.

Whatever the case, there will be a bench to think it all over. For a few minutes at least, as the security guard yawns and somebody’s footsteps echo from the high ceilings, you can ask yourself what it all means to you.

____________________________________________

When the Earth Flies Into the Sun by Derek Mong is available via Saturnalia Books.