At four in the afternoon on Monday, February 3, 1997, a uniformed chauffeur in an armored Cadillac drives the Honorable Pamela Harriman from her Paris residence on rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. Fifteen minutes later he pulls up outside the Hôtel Ritz. As Harriman climbs the red-carpeted steps past the boutiques selling diamonds and into the lobby, she looks her usual stately self. The staff greet her as one of their most distinguished visitors, and the semi-mythical “seductress of the century” rewards them with her regal smile.

Article continues after advertisement

The onetime daughter-in-law of Winston Churchill rarely sets foot outside her bedroom without full maquillage. Her leonine hair is artfully swept out and up. Her wardrobe reflects regular appearances on the fashion front row. A rigid diet and exercise regime—and a remarkable facelift—means she looks two decades younger than her seventy-six years. The effect is immaculate but subtle as befits President Clinton’s handpicked envoy to France.

She learned to muster her privilege and fame to try to win it on behalf of those who did not have what she had. And, most of all, to bring peace.

Pamela is almost forgotten now—and if she is remembered at all, it is with disdain or condescension—but on this day she is arguably the most famous diplomat in the world and the most powerful courtesan in history. Even so, few know how Her Excellency daringly used sex to cement the vital Special Relationship between Britain and America during the Second World War. Or how she helped landmark figures—some of the political or industrial “kings” of the twentieth century—to achieve and wield power. Or how she even played a part in ending the Cold War.

She commands the respect of politicians, spies and diplomats who have worked with her across two continents and five decades, with an unrivaled address book and instant access to the leaders of the United States and France. Once she was barred from mixing with royalty and banned from embassies as “that red-headed tart,” but now she presides over the grandest embassy of all. Her eminence is remarkable given that as a British-born aristocrat without a single paper qualification, this is her first formal job.

Yet as many loathe her as love her, and she is the subject of multiple blood feuds, four excoriating books and a litany of lawsuits. A chorus of critics dismiss her as a lightweight, but why, if a B-movie actor can become President Reagan, cannot such a woman become Madame l’ambassadeur?

Pamela is nursing a crushing headache as she descends the marbled hotel stairs to the Ritz Health Club and peers through the curtains of the balcony to see who is in the pool below. Often it is cleared for her to swim in private, but she has come without notice today at the urging of her deputy, who is concerned about his boss. He knows she has recently asked a saddened president to be relieved of her duties, bringing her remarkable reign in Paris to an end.

Pamela changes into a figure-sculpting swimsuit and steps down into the most elegant indoor pool in the city, flanked by Egyptian-style pillars under a trompe l’œil sky. Younger men still fall for her glamour—including, rumor has it, one of the handsome pool attendants young enough to be her grandson. They are beguiled by her mesmerizing eyes, seductive laugh and the way she makes each feel he is the most important man in the world. She starts to swim, head proud above the water to protect her coiffure, but after twenty lengths she groans and goes limp in the water. Someone rushes to pull her out and a member of the hotel security team, Henri Paul, tries to revive her with an oxygen mask. (Seven months later his quick response will earn him the honor of driving Princess Diana, and the world’s opprobrium when she meets her death in a Paris tunnel.)

This foggy February day he is urgent yet professional as a tear rolls down Pamela’s face and she slips into unconsciousness. An ambulance roars into the Place Vendôme with siren blaring and a distressed President Jacques Chirac orders the best doctors in Paris to try to save the woman he owes so much. In Washington, President Bill Clinton gives an emotional statement about his great friend who made his own once improbable ascent possible.

These are not the only leaders to have paid court to her—Kennedy was her intimate friend; Nixon, Eisenhower and Ford sought her counsel and her company; Franklin Roosevelt demanded news of her; Nancy Reagan wanted to be her friend; the Gorbachevs were her friends; de Gaulle doted on her; the wartime Australian prime minister Robert Menzies protected her; and her onetime father-in-law Churchill depended on her. She was not a woman, as former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright observed, to “let her century pass her by.” She seized it and left an indelible mark.

Hers is a story of virtually everyone who was anyone in the twentieth century, from Nelson Mandela to Joe Biden, Truman Capote to Dennis Hopper, Ed Murrow to Gloria Steinem, the Rothschilds to the Mitfords. She counted as friends Martha Gellhorn, Max Beaverbrook, Frank Sinatra, Christian Dior and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Hers was a life born of a pandemic, forged by world war and defined by haute couture, palaces and jewels, but also by love, jealousy, fortitude, heartache, illness, daredevilry and betrayal. She received dozens of proposals of marriage and took hundreds of lovers, enjoyed countless thrills on superyachts and private jets. She hungered for the trappings of wealth, but what excited her most was power. She learned to muster her privilege and fame to try to win it on behalf of those who did not have what she had. And, most of all, to bring peace.

Narrowly missing death time and again in the Blitz, she lost precious friends to the war, and while living at Downing Street bore intimate witness to Churchill’s desperate struggle to save Britain from Hitler. Such visceral experiences left her with a compulsion to try to stop future conflict, yet her efforts were often belittled and misread. Few understand just how she became one of the twentieth century’s most influential political players. Most of what she did was kept secret by Pamela herself or ignored by others; her papers were locked away, others classified; her surviving friends were reluctant to speak.

Pamela was portrayed throughout her life…as a scheming adjunct to her men. Her death began a reappraisal that can only now be completed.

Only through four years of intense research in Britain, America and France was I able to unearth astonishing new testimony that allows us finally—three decades after her death—to appreciate the achievements of a woman whose name was trashed by the presumptions of her time. Just as I discovered when writing about her mother-in-law, Clementine Churchill—another formidable yet woefully underrated woman—history has reduced Pamela to a distorted stereotype, in her case a conniving and ridiculous gold digger obsessed by sex. And yet, struck by how both Winston and Clementine Churchill prized her very special contribution throughout the Second World War and the global significance of the demands they made of her, I was driven to find out the truth.

Perhaps only against the background of today’s perilous tensions between West and East—and the bloody invasion of Ukraine—can we begin to register the sacrifices of a twenty-year-old woman hell-bent on waging war against tyranny. Perhaps only as more evidence comes to light can we take in the full scope of the roles she played at the pinnacle of power in three countries half a century apart—a reach and longevity unmatched by virtually anyone in modern times. Or recognize how the grit of one woman of astonishing skill but little education could help lay the groundwork for, and later revive, transatlantic alliances once again being put to the ultimate test.

Newly discovered papers, private letters and diaries, fresh accounts—and the transcripts of extensive interviews with her released for the first time—reveal how the real Pamela bore only passing resemblance to her reputation. Together they paint a nuanced character whose obvious faults were outweighed by an exceptional zest for life and reinvention, combined with experience and gifts unlikely to be seen in one person again. And yet her star sometimes shone too brightly; her access to power drew unfriendly fire. She had the temerity to succeed when failure should—in her critics’ eyes—have been her due.

When her son Winston phoned a family friend to announce her death, he spoke of how her “extraordinary and dramatic exit” befitted his “extraordinary, dramatic mother.” News of her demise was marked by an outpouring of grief but also, in some quarters, uncontained pleasure. Pamela was portrayed throughout her life, including in two weighty biographies, Life of the Party and Reflected Glory, as a scheming adjunct to her men. Her death began a reappraisal that can only now be completed. One of her closest friends, Richard Holbrooke, a tough-nut diplomat stricken by sorrow at her passing, cited the philosopher Søren Kierkegaard to observe that while life is lived forward it is best understood backward. And so the thrilling and astonishing “arc that Pamela Harriman traveled” should start, Holbrooke advised us, “by beginning at its end with her ambassadorship to France.” For the evening of her life—when she finally achieved her seemingly impossible dreams—gave a “different meaning” to everything that had gone before. After half a century of being defined by powerful men, this was when she proved herself a singular force on her own account. And yet few appreciated what she managed to do. Or how it ultimately led an exceptional figure of the twentieth century to a lonely death.

__________________________________

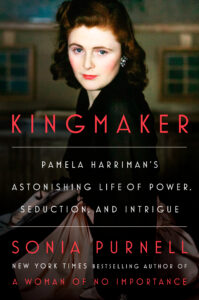

From Kingmaker: Pamela Harriman’s Astonishing Life of Power, Seduction, and Intrigue by Sonia Purnell. Copyright © 2024. Published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.