Skift Take

In-person sporting events are some of the last great communal gathering spots. We travel en masse to take-in competition, cheer on our teams and experience life. As a result, sports tourism has become an absolute economic juggernaut for the travel industry. In the immortal words of Jerry Maguire – Show Me The Money!

– Sarah Kopit

Raymond Fox had no intention of traveling to Germany for this year’s Euro 2024 soccer tournament. As a 50-something British expat settled in Brooklyn, he has responsibilities – a job, a family, and keeping up with NYC’s alternate-side of the street parking. And Berlin, well, it’s a bit of a trek.

But mere hours before the semifinal match between England and the Netherlands, Raymond (not his real name) felt a familiar itch. He rang his UK-based travel partner and cousin, Matt. They made a pact: if England won, they would travel to Germany to watch their team in the final.

At 4:44 p.m., England clinched its spot with a breathtaking last-minute goal. By 4:52 p.m., Raymond shelled out $1,400 on StubHub for a ticket to the final match. Fifteen minutes later he bought a $1,200 Norse Atlantic Airways flight from JFK to Berlin on Expedia.

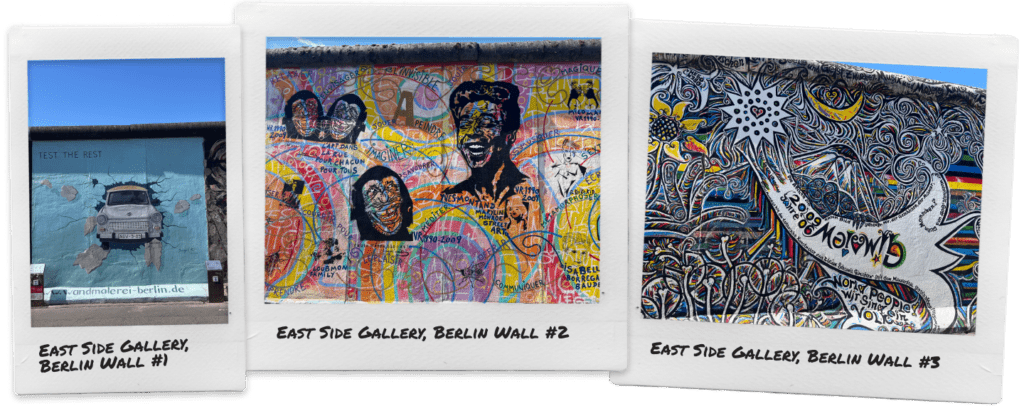

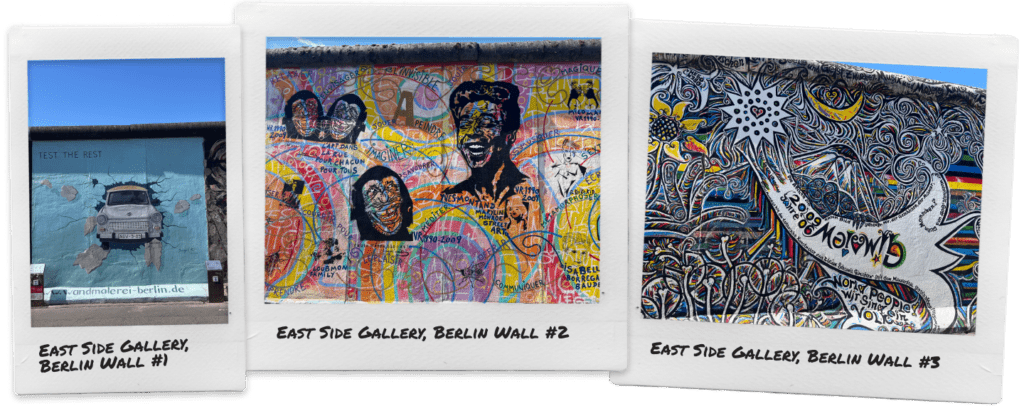

Raymond didn’t sort out his accommodations until he was online at the airport the next evening. He chose the Schultz Hotel in Berlin, paying around $800 for its proximity to the East Side Gallery, a famed stretch of the Berlin Wall adorned with international murals.

Yes, the game was important. But so was the experience of being in Berlin along with thousands of other fans. After all, he could have just stayed in Brooklyn and watched the match on the telly.

“On my first day, I joined a three-and-a-half-hour guided bike tour to get a feel for the city,” Raymond recounted. “Over the next three days, I hit 23 tourist sites, restaurants, bars, nightclubs, and finally the iconic Olympiastadion Berlin, where Jesse Owens won four gold medals in the 1936 Olympics.”

Unfortunately for Raymond, England lost.

Just Do It

While Raymond’s story may be unique in its spontaneity, the fundamentals are basic. Every year, in both small towns and urban centers across the globe, millions of people will travel to experience the excitement of in-person sports.

For some fans, they’ll drive to the next town over to watch their home team face off against local rivals. Others will embark on more extensive treks, boarding planes, trains, and automobiles to experience the pinnacle of international competition.

They’ll flock to baseball diamonds, tennis courts, and cricket grounds. They’ll thrill at the sight of race cars zipping through ancient cities. And then, inevitably, there’s the Beautiful Game. Known to Americans as soccer and the rest of the world as football, for these fans it’s not just a matter of sport but a way of life.

The common thread: people coming together, not virtually but in real life. And the travel industry is here for it, happily providing everything fans need to make the trip – all while turning a tidy profit in the process.

Raymond has already started planning for the next World Cup. He attends every four years, no matter what.

“I’ll budget around $10,000 for the 2026 tournament, one week in Mexico, one week on the West Coast, and day trips to matches on the East Coast that I can drive to from Brooklyn,” Raymond says. “But if England gets to the final, and I have to reach for StubHub again, then that will probably add another 50% for one match.”

Taken together, that’s big (big!) business for the travel sector.

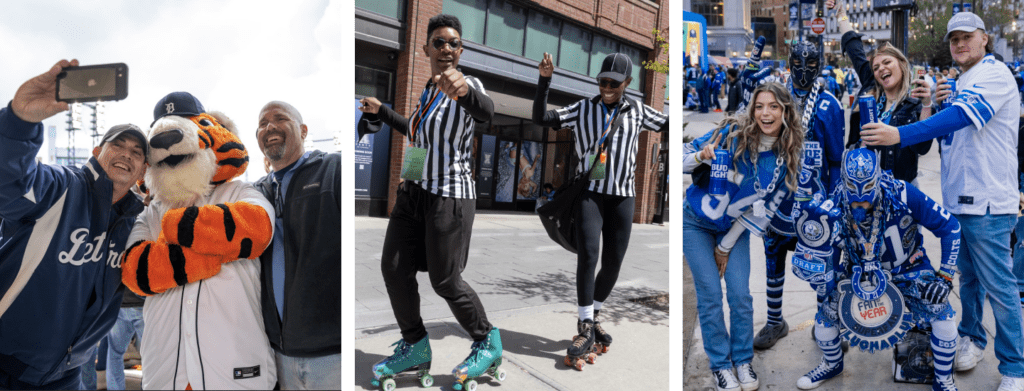

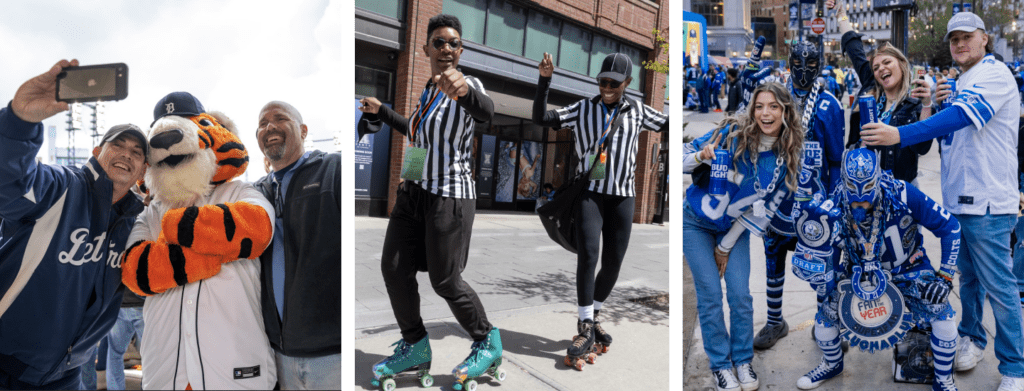

Source: Visit Detroit

In 2022, the global sports tourism market was valued at $587.9 billion, according to Grand View Research. And the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis says Americans alone spent $6 billion on spectator sports, like watching professional baseball, and $22 billion on participation sports, like traveling for a ski trip.

Moneyball

But even more important for the industry than what’s happening now, is where sports tourism is going. The answer: up and to the right. The market is exploding, and projected to reach $2.1 trillion by 2030, with a compound annual growth rate of 17.5%.

The bulk of the money comes from the world’s mega sporting events, like the Olympic Games, Formula 1, the World Cup and the NFL’s Super Bowl. For the International Federation of Association Football, commonly known as FIFA, the 2022 World Cup in Qatar brought 3.4 million spectators to stadiums with record revenue of $5.8 billion. It was the most profitable World Cup ever. Formula 1, which holds races globally all year, had 5.7 million fans come out in 2022. That’s up 36% compared to 2019. Revenues reached $2.5 billion.

But the granddaddy of sports tourism events is the Super Bowl. Its latest installment, Super Bowl LVIII in Las Vegas, shattered all sorts of records, in no small part because of a force of nature named Taylor Swift, whose romance with the Kansas City Chiefs tight end Travis Kelce catapulted viewership into the stratosphere and brought in a whole new generation (and gender) of fans to the sport. An estimated $14 billion was generated by U.S. businesses because of that game alone, according to Gametime.

Detroit Rock City

Venues, hotels and airlines are not the only ones cashing in from sports tourism. The destinations are getting just as rich.

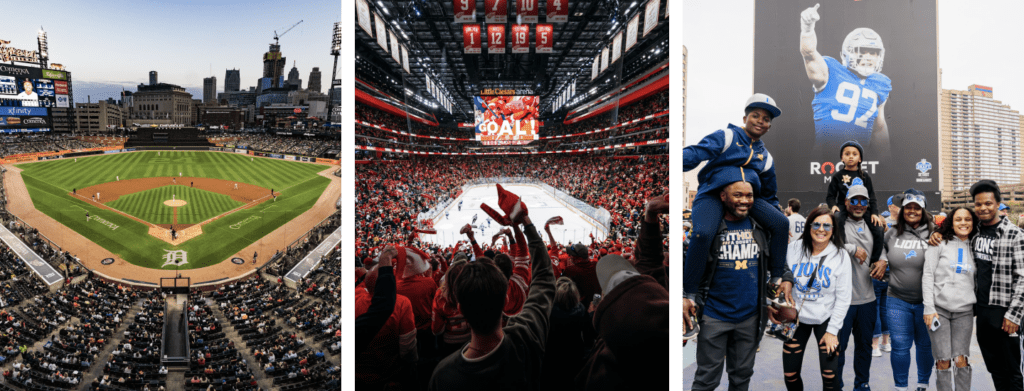

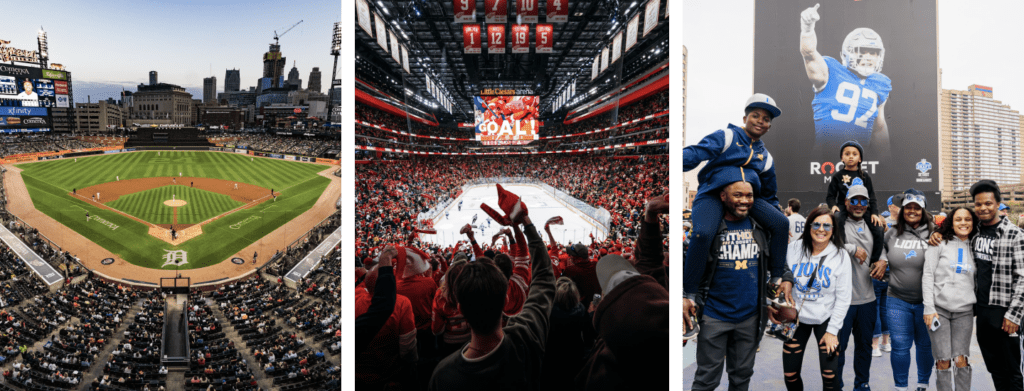

Consider Detroit, Michigan – home to the auto industry, Motown, this writer, the Detroit Lions and Michigan Wolverines (Go Blue!).

Much of the city’s economic rebirth is credited to bringing Detroit’s four professional sports teams back to the heart of the city’s downtown from crumbling stadiums in the suburbs, says Chris Moyer of Visit Detroit, the city’s official convention and visitors bureau.

Source: Visit Detroit

Last year, the Detroit Lions had their first winning season in many fans’ lifetime. Moyer says the phenomenon of Victory Monday – where the community basks in the afterglow of a triumphant weekend win – was alive and well in Detroit. It’s a real thing that translates into real dollars. On those Victory Mondays, Michiganders were far more likely to open their wallets, says Moyer. And hotels felt the love too. When the Detroit Lions played at home, Sunday occupancy rates averaged 9.6% higher than fall weekends without a home Lions game.

This year, Detroit also hosted the NFL Draft.

The three-day event generated $213.6 million for the city, according to organizers. Fans from all 50 U.S. states and more than 20 countries gathered together in the Motor City. That includes one fan from Australia who flew more than 11,000 miles to attend. Detroit hotel occupancy during that period reached a high of 92%.

“There’s something special happening in Detroit,” Moyer says. “And sports is a big part of it.”

Welcome to Hamtramck

And it’s not just the big professional teams making noise. The little guys are getting a piece of the action as well. Take the Detroit City Football Club, a community based, semi-pro outfit located in the predominantly Polish community of Hamtramck, 13 miles outside the city center.

“Five local guys wanted to start a grassroots community team,” Moyer says. “One year later they did tryouts.” 100 people showed up. That was back in 2011.

“Now they’re in the division right below the MLS called the United Soccer League,” Moyer says, slyly throwing in that he’s also a part owner. “I’m genuinely proud. I have two shares,” he chuckles.

Source: Detroit City Football Club

Prior to each home contest, DCFC supporters meet at a local Hamtramck bar. About a half hour before kick-off the players – dressed in their full kit – and fans parade to the stadium. It’s called the March to the Match, complete with drumming, singing and pyrotechnics (yes, really).

There’s both a men’s and a women’s squad.

And if you think you’ve heard something like this before – you have. This community-owned soccer business model was made familiar to Americans by actors Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney in their docu-series “Welcome to Wrexham.”

Family Ties

So what’s a sports fan to do when there’s a crucial game or match to be watched, but the family wants to go on vacation too? Increasingly, you bring them.

When one person travels for sport, and the rest of the family comes for leisure – everyone wins, including the local economy. These secondary effects around sporting events have significant monetary upside.

Airbnb has capitalized on the accommodation needs of sports fans. In the first half of 2022, the company says its hosts earned over $30 million during major sporting events. The US Open in Miami drew over 60,000 guests and generated nearly $17 million in host earnings. The Formula 1 Grand Prix, also in Miami, had nearly 16,500 guest arrivals and netted hosts about $4 million. And during the Super Bowl in 2023, more than 45,000 groups checked-in to Phoenix Airbnbs, according to the company. $1.3 billion was added to the local economy.

Raymond says when he can plan ahead, like for the World Cup, it’s very much a family vacation with football matches peppered throughout.

“If we stay more than a week in one city, I’ll book a house, and usually arrange with friends and family to meet,” he says.

On the family trip to the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, “my wife and then 1-year old son stayed in a game reserve, a winery, and on an overnight luxury train from Johannesburg to Cape Town. I dived with Great White sharks on the southern tip of Africa.”

If You Build It, Will They Come?

But for the cities hosting mega sporting events that require massive infrastructure investment, it’s not always a slam dunk. Nor are they without controversy. And no event has been more marred recently than the Olympic Games.

Host countries face immense financial burdens to put on the games – often with disappointing economic payoffs. Nations invest billions in infrastructure, stadiums, and facilities, hoping to boost tourism, their global image, and local economies. However, too often it doesn’t go according to plan.

Many of the venues built for the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics are now abandoned or underused. Promised urban improvements, like better sewage systems and housing projects, were not completed, leaving the city with unfinished and wasted investments.

Similarly, the 2004 Olympics in Athens put Greece into debt and left numerous abandoned facilities, worsening the country’s financial crisis. The Sochi 2014 Winter Olympics are said to have caused environmental damage, with construction projects hurting protected natural areas.

For the upcoming 2024 games in Paris, the city is managing economic expectations, saying that they are playing the long game.

Corinne Menegaux, director general of Paris je t’aime, the city’s tourism board, told Skift that it doesn’t expect the games will be a major international tourism draw. In fact, Paris sees only 30% of the event attendees coming from abroad.

Rather, the city expects a massive upside value in the images of professional breakdancing, skateboarding and beach volleyball being played in front of its iconic landmarks like the Eiffel Tower.

“It’s a way of showing that Paris is really implicated in this urban culture.”

Flexing That Social Muscle

And if the global Covid-19 pandemic showed us nothing else, it’s that humans are social creatures who benefit enormously from in-person interaction. Intuitively, of course, it makes sense that live, community events like sports are good for our mental health – when we get together with our friends and loved ones, our dopamine and serotonin work overtime.

Scientists in the UK actually tested this theory and it came back conclusive: attending live sports does, in fact, boost our sense of wellbeing and reduces loneliness. Parents and children bond over sport (yet another reason that the Swift/Kelce juggernaut was a boon for dads and tween daughters everywhere). Team alliances are passed down from generation to generation. Season tickets for the Green Bay Packers are famously a part of many holders’ estate plans.

For Raymond, who lives a continent away from his extended family, this aspect of sport is incredibly important. “I travel to every event with my cousin Matt, so for us it’s a great way to keep in touch with family,” he says. “I know I’ll see him every 4 years at least for the World Cup.”

On the Berlin trip this past weekend, cousin Matt’s 19-year-old son (and Raymond’s nephew) came along. So now they are three. “My son is 15,” Raymond says with a smile. “He will join us soon enough.”

In the early days, before the kids came along, Raymond would arrange trips to watch footie with groups of friends who lived on three different continents. For the 2004 Euro championship in Portugal, he rented a 20 person villa, had an excel spreadsheet to track everyone’s comings and goings, and organized more than 100 tickets a day – for 3 weeks.

And 20 years later, “two of those people were in Berlin with us last weekend,” he says.

For the 2002 Japan and Korea World Cup, Raymond and 15 friends in Hong Kong bought tickets to every Brazil game. “So in between matches we went our separate ways touring Japan,” he remembers. “Then we’d meet up every 3 days sitting next to each other in a different stadium.”

And every time Liverpool reaches a European final, Raymond meets a group of friends that have been at the same matches over the years.

“New friends join, some drop out,” Raymond says. “But we’re there every time.”

Sports tourism is part passion, part obsession, and a total economic goliath. Dedicated fans who cross countries and continents are driven by their love for the game and the community it fosters.

“I met a couple from Canada at the 2022 Qatar World Cup,” he says. They swapped numbers and he’s looking forward to reconnecting in 2026.

How long will he keep doing this? “I’ve budgeted World Cups into my retirement planning,” Raymond says. “As long as I’m mobile, I’m going!”

Sarah Kopit is editor-in-chief at Skift. Contact her at [email protected]

Graphics by Beatrice Tagliaferri

Have a confidential tip for Skift? Get in touch