Paul Auster (1947-2024) was the author of more than thirty works of poetry, fiction, nonfiction, and screenplays. His books have been translated into more than forty languages. His death on April 30, 2024, prompted an outpouring of countless tributes around the world. Below are reminiscences from those closest to Paul followed by links to some of the international publications.

___________________________

SIRI HUSTVEDT

“The Mechanics of Reality”

I could usually see a story rising up in my husband before he began telling it, the intake of air, the concentration in his eyes, and, almost always, a hint of humor in the set of his mouth. He liked to take his time with narration, to set the stage, and to create just enough suspense to keep his listeners rapt.

Paul loved stories, his own and those that belonged to others. He loved to read them, listen to them, write them, and tell them at dinner tables, in cabs, in doctors’ offices, and lying in bed beside me at night. He understood the rhythm, shape, and surprise necessary for a good story. He knew what to put in and what to leave out. His phrase “the mechanics of reality” described a belief central to his work. Human lives do not conform to the dull dictates of cultural conventions that pinch perception, distort the world, and claim to represent the real. The mechanics of reality include wild coincidence, astounding fact, and bizarre discovery, or so it seems to us. All such events appear through the filter of human consciousness. We select bits of pieces of experience, turn them into narratives, and make meaning from them.

The universe is indifferent.

In The Red Notebook, Paul’s collection of true stories, he tells about a woman he met in Paris at a publisher’s office. After she left the room, the editor recounted the following tale: The woman was born in Prague during the Second World War. While she was still an infant, her father was arrested and conscripted into the German Army. She and her mother never heard from him again. She grew up, became a professor of art history, fell in love with one of her students who hailed from East Germany, and married him. Shortly after the wedding, her husband’s father died. They traveled to his hometown to attend the funeral. It was then they discovered that his father and her father were one and the same man. She had married her brother.

In Moll Flanders (1722), Dafoe’s fictional heroine discovers that she has, like the real art historian, accidentally married her half brother.

When Paul was fourteen years old at summer camp, he and several others were caught in a storm. The group was headed to a clearing for safety. Paul was standing behind a boy who crawled under a barbed wire fence when a bolt of lightning struck. The boy died instantly. Neither the campers nor the counselors knew the child was dead. Paul remembered vividly how hard they worked to revive him.

The imagination is born of memory. In this case, traumatic memory: the vision of a motionless young body Paul knew could have been his own corpse.

When he spoke of “the mechanics of reality,” Paul was not referring to literary high jinks or arch cleverness that trades in the improbable for fun. He was articulating the complex patterns of often unpredictable interactions that affect every life and which became part of his fiction.

In an article in the New York Times that appeared under my husband’s obituary, the writer Lucy Sante makes a typical error. She mistakes depth as surface: “Paul was fascinated by nineteenth-century melodrama with its preposterous coincidences and bifurcating plots.” As someone who lived with “Paul” for forty-three years, was his first reader and editor, as he was mine, I can confidently say Paul had no interest whatsoever in theatrical melodrama. But even if “melodrama” here is used as imprecise code for the plot machinery in some, not all, novels of the period (which I think it is), the statement represents a fundamental misunderstanding of Paul’s work, one which continues to thrive in the United States and the UK.

In the rest of the world, continental Europe, Central and South America, Asia, and the Middle East, Paul Auster is another writer altogether. His work has been translated into over forty languages, testimony, I think, to the power of his stories. It may be that in cultures with much longer and varied literary histories than our own, cultures that revere writers and where intellectuals are not regarded as enemies of the people, in cultures where the neoliberal fantasy of isolated self-creation has less appeal, the vicissitudes of life and their representations in a novel are seen as meditations, often tender, on “the music of chance.”

City of Glass, the first volume of The New York Trilogy, the book that made Paul’s reputation, was rejected by eighteen New York publishers. Several editors liked the book, but they wanted him to change the ending. He refused. Rejection hurts. I know. I witnessed it. Compromise would have been far worse.

Playing with conventions, literary or social, taking them apart and exposing them as scaffolding that hides rather than reveals truths can be threatening to those who think they know exactly how the world is supposed to turn. The Trilogy repositions the reader. It forces her to see the world differently. That’s the magic.

In an interview, Paul said City of Glass was “in an exaggerated way” what might have happened to him if he hadn’t met me. If he hadn’t told me the same thing, the thought would not have entered my head. In the book, its hero, Quinn, briefly meets the fictional “me.” I told Paul it was the first time I was able to shake my own hand.

It’s true he often said, “What would have happened to me if I hadn’t met you?”

And what would have happened to me if I hadn’t met him?

We met on February 23, 1981, after a poetry reading at the 92nd Street Y. I had just turned twenty-six, was working toward a PhD in English at Columbia University, and had published a few poems in literary magazines. He was thirty-four, had published several books of poetry, and was writing The Book of Memory, the second part of his memoir The Invention of Solitude.

Paul looked at his own death with a fierce clarity and unbending courage I have never seen in another human being.

In 4 3 2 1 Paul played out a long dance of WHAT IF. He wrote four different stories for the same Archie Ferguson, life variations dependent on the twists and turns of a boy’s changing circumstances.

He knew and I know that if we hadn’t met, he and I would have become different people, not wholly different people, but we would have been pushed and pulled in directions that would have changed us. We, all of us, are enmeshed in the mechanics of reality, and those realities, many of which are not of our own making, can be terrible. Heartbreaking. They may wound us for life or even kill us.

While Paul was working on his last novel, Baumgartner, he began to suffer from fevers every afternoon. Although we didn’t know it at the time, the fevers were a symptom of pneumonia caused by his cancer. It meant he had to stop working much earlier in the day than usual. As he read the book aloud to me in regular installments, he said over and over, “I have no idea what I’m doing.” And for the first time in the history of our long literary companionship, I had no criticisms, no words or passages I thought should be cut or changed. “Keep going,” I said, “I love it. Just keep going.”

Paul finished his book about an old man still grieving his wife, Anna, a poet, who died years earlier in a swimming accident. Paul isn’t Baumgartner, and I am not Anna, who never bothered to publish her work, but when I first listened to the novel and then read the manuscript silently to myself, I felt, to rephrase Wordsworth, intimations of mortality.

I also know the imagination is a tool of the unconscious. Paul was writing, not only a preamble to his own possible death, but a book that eerily anticipated my grief, not his. We often pitied the one who would survive the other and become the second body interred in the double grave we purchased in Green-Wood Cemetery years ago. It turns out, I’m the one who will go on top.

Paul looked at his own death with a fierce clarity and unbending courage I have never seen in another human being. “I’d like to die telling a joke,” he said. A joke, of course, is a bite-sized narrative. He hoped he would have time to relate one last little story. That didn’t happen, but his desire to do so is beautiful to me.

And I, like Baumgartner, remain, an amputee afflicted with phantom limb syndrome. That was the metaphor Paul used for Sy Baumgartner’s mourning. Before he wrote about the phenomenon, he asked me to pick out some of my neurology books and papers (not too abstruse) so he could read up on it. The trope is apt. A part of me has gone missing, and that absence hurts like hell. But when I look up and out at the world, I see that the mechanics of reality churn on.

___________________________

DON DELILLO

Paul and I were the best of friends for many years. Walking, talking, traveling—from this distance it seems nonstop. And in recent years, he and Siri came to visit after medical appointments at a nearby hospital where he was being treated. Old times, good times, these were the pleasures we carried with us whatever the current circumstances.

And baseball games in Boston and New York, and film festivals in Portugal, and quiet times at an old farmhouse in Vermont.

Friendships endure well into the afterlife of one of the friends.

___________________________

JM COETZEE

It was my great good fortune to enjoy the friendship of Paul Auster, to share summer vacations with him and his beloved Siri, he and I a comedy duo, he the bon viveur and raconteur (1950s Brooklyn; quirks in the history of baseball), I the puritan spoilsport and pedant.

I spent my working life in universities, knew plenty of esteemed literary scholars, but when it came to matters of judgment trusted Paul above any of them. He had read everything, had total recall, went straight to the heart of a book like a rapier thrust.

I once shared a cab with him to an engagement in Buenos Aires. The cab was mobbed by teenage girls thumping the bodywork and calling Paul! Paul! There he was: a dedicated writer, a real workhorse à la Balzac, yet a worldwide celebrity too: who else has achieved that since the days of Byron?

The one mistake Paul made was to become famous too early. Readers enter the house of Auster via The New York Trilogy and miss out on later masterpieces like 4 3 2 1 or the book on Stephen Crane, over which he sweated blood.

He had a hard death. He did not deserve that. There must have been some petty god on Olympus whose envy he aroused.

___________________________

FRANK HUYLER

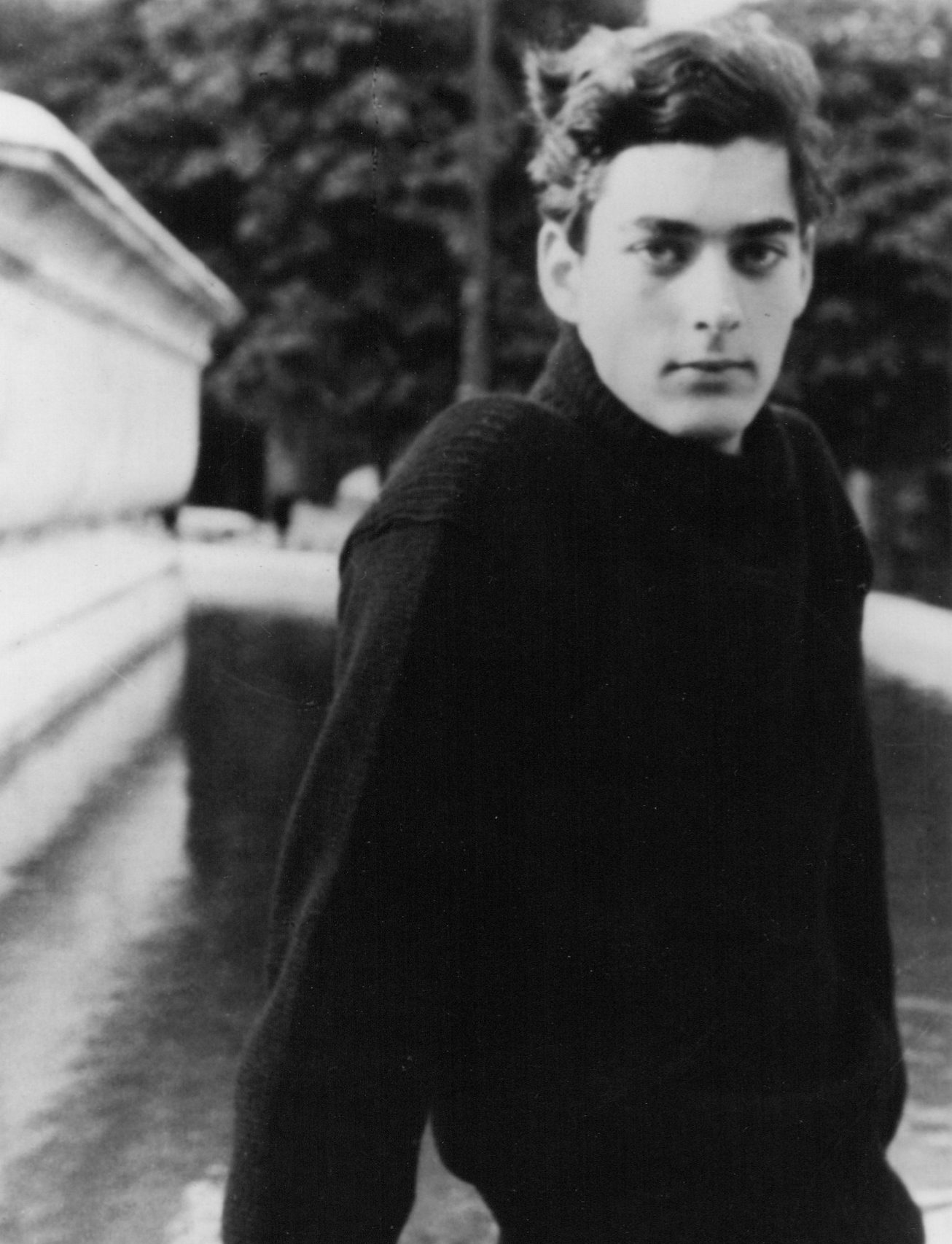

In photographs, especially those taken in recent years, Paul Auster looked formidable, severe, stern. He had an intense stare that radiated critical intelligence. In interviews he often came across, correctly, as serious and imposing.

All of this misses a fundamental truth about him. Although he was an intimidating figure in many ways—he didn’t suffer fools, and was entirely confident, with a vast amount of knowledge on full display—underneath it he was an enormously good-hearted and generous person whose inherent warmth too often escaped formal notice.

Above all else, Paul was a humanist. He loved the world and the people in it. He had a sense of humor. He was earthy and vital and much lighter than he seemed. And it was this humanity, I think, that accounted for much of his success among readers around the globe. While a great deal has been said about the influences of postmodernism in his work, not enough has been said about the ethical sensibility that so deeply informed it.

Paul was the best kind of American. He believed profoundly in democracy and the principles of the Enlightenment. He defended human rights, and free speech, and was willing to confront those who didn’t, as his sharply worded 2012 public exchange with Recep Erdogan, autocratic prime minister of Turkey, so clearly shows.

He wasn’t content to simply comment on these themes, either. In 2019, appalled by the antidemocratic forces on the rise in the United States, he cofounded Writers for Democratic Action, an advocacy group seeking to register voters around the country. He and other cofounders—including his wife, the novelist Siri Hustvedt—enlisted writers from all over the world to participate in this ongoing effort.

His knowledge of American politics, like his knowledge of many subjects, was specific, deep, and impassioned. He knew what was going on in both the Senate and the House, as well as in battleground states, in surprising detail. Above all, he understood the stakes, and did, in practical terms, what he could to fight for them.

As another example of his essential nature, take two of his most recent books—Burning Boy and Bloodbath Nation. At first glance they are profoundly different from one another, but they are united in important ways. They both look outward, they both seek to redress wrongs, and are both moral efforts.

In Burning Boy, he sought to elevate a figure he saw as unfairly neglected in American letters—Stephen Crane—to greater prominence. There is no question that he identified with Crane, and with Crane’s youthful passion and talent that tragically never reached full maturity. At 800 pages, Burning Boy was an exuberant labor of love, and is clearly the best biography ever written about Stephen Crane. But it’s also a celebration of the artistic enterprise itself, and in this sense is about far more than Stephen Crane. It’s about the spirit he saw in Crane, a quality that transcends both individuals and eras, and looks forward, with a redeeming and ultimately hopeful power.

Bloodbath Nation, on the other hand, is an exercise in minimalism. At a mere 140 pages of text, it sought to illuminate one of the darkest and most mystifying elements of American life: this country’s love of guns and pointless violence. It was an attempt to explore the inexplicable, in the hope that people might step back, and reconsider, and stop accepting the aberrant as normal. Like Burning Boy, it is intensely personal, but it is also a book that looks outward, and calls for change even as it tilts at windmills.

There is of course much more to say about his work. But my point here is simple: he cared deeply about the world around him, and was invested in the fates of other people, even those he’d never met.

I knew him for more than two decades. It was an unlikely friendship, and one that had unexpectedly grown in recent years. We met due to writing but did not remain friends because of it. Many of those who were close to him are household names in the arts; I’m an ER doctor in Albuquerque, New Mexico. And it is in this area—that of illness, death, and the facing of it—that I am perhaps best equipped to talk about him.

I’ve been a doctor for a long time and have rarely seen someone look so directly and clearly at their own mortality. He stared straight at it from the start.

“I’m not a baby,” he said to me, more than once. He meant it, and he wasn’t. His was an essential toughness, a kind of primal rigor, and I think he discovered something about himself when he was put so cruelly to the test. None of us know how we will react to a diagnosis like that. We don’t know if we’ll be strong, or weak, brave, or self-pitying, resigned, or angry, or some impossible combination of all these things.

He was hopeful at first, but as the ordeal progressed—and it was a terrible one, make no mistake—he bore it with a striking combination of stoicism, courage, warmth, and grace. He knew what he was facing from the start, and made no secret of it. He spoke openly and frankly, without pretense. He wondered aloud about death. And when I asked him once if he ever regretted smoking, something he loved and even made a movie about, he was true to himself to the end.

“No,” he said, which to me seemed both fitting and right, “I’ve thought about it and I don’t.”

As his condition worsened, he never sought the last refuge of the dying, which is detachment. He never withdrew from those close him, or the world around him. He remained as politically engaged as ever. His overwhelming concern, as his death approached, was for his family—for his wife, Siri, his daughter, Sophie, his son-in-law, Spencer, and finally the last true bright spot of his life, his new grandson, Miles, to whom he spent his final days writing letters.

He cared deeply about the world around him, and was invested in the fates of other people, even those he’d never met.

Paul’s last book, Baumgartner, was written when he was sick. He didn’t know he had lung cancer, only that he was coughing and felt rotten. But the novel is revealing—it’s about the end, and the struggles of the end. He drove himself to finish it, just as he drove himself so hard for most of his life, discharging his essential restlessness, armed with a mysterious sense of purpose that I’m not sure he fully understood himself.

Finally, here is a personal example of his kindness: during the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, before vaccines were available, and all of us in medicine were taking a bath in a malevolent virus with criminally inadequate protection, I moved to a small apartment so I wouldn’t bring it home to my family. I was not alone in this—many healthcare workers did the same. It was a dreary, frightening time, and my life was reduced to shifts in the hospital, alternating with the solitude of a one-room studio next to the interstate.

One of the people who called me the most during this wretched period was Paul. Every so often the phone would ring, and it would be him, checking up on me. And they weren’t short conversations. They were long ones. We talked about the usual stuff—politics and books and so on—a little bit like college students. Then he would tell me stories, endlessly entertaining anecdotes from his remarkable life that included people like his friend Salman Rushdie and the King of Spain.

When he learned his cancer had spread he asked me to come see him, and I went briefly to New York to say goodbye. Just a few weeks ago we sat in his book-filled study and watched TV. Both the Knicks and the Mets were playing at the same time, and he kept flipping back and forth between channels. He offered a purist’s argument that the three-point shot had damaged basketball by disrupting the true flow of the game. He grudgingly acknowledged my counter argument that the three-pointer makes everything more exciting. Then, between remarks like that, or running commentary on the plays before us, he’d ask me other things. How long did I think he had? A few more months, possibly? If he were embalmed, would it mean his body would be unnaturally preserved in the earth? This, he said, was something he did not want. He intended to become part of the natural world again, with all that this process entails.

The games were close. He knew every player on the Knicks, and every player on Mets, and how each of their seasons had gone. Surprisingly, both of his teams won by a whisker. He was not overjoyed, but he was quietly pleased. In fact, he seemed to take some measure of personal credit for their victories, like the true fan he was.

At one point we looked at his long list of books—the “Also by Paul Auster” page in Bloodbath Nation, which sat conveniently on his coffee table.

Many writers, even famous ones, hesitate when considering some of their past efforts.

Not him. He studied the list and spoke many of the titles aloud. He disavowed nothing, was proud of them all, and there was a sweetness to his pride, even a kind of earnestness and innocence. When I asked him to pick a favorite, he simply said they were all his children, and I was happy for him.

When the games were over, and his extended family was coming for dinner, I stood up to go. We both knew that was it, and this moment will remain with me. I could see that he didn’t have much time left, but I didn’t question his hope for a few more months. He didn’t want to die, but he was right to stop all treatment when he did, and I told him so. I also told him that the worst was behind him, and I believe this was true also. Then I flew home to New Mexico, back to another world.

Paul Auster was wise, loyal, loving, and kind, a man whose virtues dwarfed his flaws, and whose brilliance never outshone his decency. When he died, which I read about online just like so many others in so many places, I had the immediate and powerful desire to pick up the phone and call him. I wanted to congratulate him on his extraordinary life, on the beautiful and astonishing books he wrote, to thank him for the example he set, and to tell him that I missed him already.

___________________________

CAROLYN FORCHÉ

It was through his spare, philosophical poetry that I first knew Paul Auster, and reading backwards through his work now, the poems glimmer, tightly coiled like watch springs, and from them sprang the music of the prose that was to come, the novels, films, and memoirs. It is all there in the poems, wound up and ticking. When I lived in New York, I found the heart of the city through his New York Trilogy. When later I lived in Paris, his bilingual anthology of French poetry took me by the hand in French. He had gone before me into French poetry, and without his translations I wouldn’t have known The Notebooks of Joseph Joubert or the poetry of Jacques Dupin. He knew and had translated or written about everyone I loved: Rene Char, Yves Bonnefoy, Edmond Jabès. When I finally met him and became his friend, it was as if I were meeting someone who had always been there.

A week or so before he died, I visited Paul and Siri, along with my son, Sean, a friend of their daughter, Sophie, and her husband, Spencer. We sat in the light-filled library, his favorite room in the house, talking about Immanuel Kant and the New York Mets, the beauty of Green-Wood Cemetery, the ordeal of his illness. His mood was by turns light and pensive. “I love this room,” he said. “I’m going to die in this room.” And then he teased me about how long it took me to write my memoir (fifteen years). His last words were “Listen, you have to live a long time. You have to write a lot of books.” I said I would be back in a week and gave him a hug. You will close your eyes, he wrote in a poem, in the eye of the crow who flies before you / you will watch yourself / leave yourself behind.

___________________________

PAUL YAMAZAKI

Paul Auster’s The Invention of Solitude was one of the first hardcovers to appear on the shelves of City Lights in 1982—up to then City Lights had been a paperbacks-only bookstore. In the years that followed every new book from Paul was cause for celebration at City Lights. I would like to share, to borrow a phrase from Paul, some “magnificently useless” moments that recall Paul’s enthusiasms, curiosity, and generosity.

I happened to run into Paul at a book convention in Miami in 1993. We got into a conversation about the New York Knicks who were in the midst of a postseason playoff run and he was very curious to see how his team was doing. One of us suggested that we momentarily suspend our professional obligations and leave the convention to find a bar nearby to watch a few moments of the Knicks game. Those few moments turned into a whole quarter of play before our sense of professional responsibility overcame us and we returned to the convention.

At another convention a few years later in Chicago a chance meeting in the aisles of the convention led Paul to suggest that we step outside to enjoy a little fresh air. Once outside Paul shared with me his pleasure and wonderment at attending the Cannes Film Festival. The moment was brief but it was wonderful to bask in his recollection of a pleasurable experience.

My favorite recollection is walking down Seventh Ave. in Park Slope with Paul because he wanted to share with me his neighborhood bookstore, which was Community Bookstore. Community Bookstore then and now is a reader’s delight with a carefully chosen selection of titles. The memory that I will always carry of Paul is of him browsing through their fiction backlist and pausing in the Ds and happily declaring that they had a nice selection of Dickens and Dostoevsky. It is my hope that in the future City Lights will continue to delight readers in the similar fashion with our selection of Paul’s titles.

___________________________

ASTI HUSTVEDT

I loved Paul. I love all of my brothers-in-law, but Paul was my brother, no need for the in-law qualifier. I find it impossible that he’s gone.

I was either nineteen or twenty when we first met. Since he’s the only one who would know the exact date, and he’s no longer here, I might never know for sure. Paul’s memory was a wizard. Not once did I win an argument with him about a fact, a date, a name, or an event. He never needed to google, which is a good thing because he managed to get through life without ever using a computer. Not long before he died, we watched Dr. Erlich’s Last Bullet together, a 1940s movie starring Edward G. Robinson and, as usual, he named each and every actor in each and every scene, no matter how obscure.

Listening to Paul talk about books—writing them and reading them—changed how I read, how I want to read, how I think we should all read.

But books, not movies, were my first deep connection to Paul. Even though I don’t remember the exact year we met, I know I was in college, a comp lit major studying French. I was dazzled by his deep and personal knowledge of France and French literature, and he was incredibly kind to me—he made me feel smart, even when I no doubt made naive, derivative, or pretentious comments about whatever French author we were discussing. I went on to graduate school in Paris, where Paul found me my first apartment, and made sure that his French friends—some of them famous figures—looked out for me. Paul didn’t only introduce me to people, he introduced me to books not included in my curriculum: his own brilliant, meticulous, and achingly tender books, of course, but he also introduced me to Celine’s propulsive and combative prose, Bataille’s perverse erotic novellas, Georges Perec’s wacky word play and so many others.

In graduate school, I was fully indoctrinated into French theory, doing my best to deconstruct the texts I was reading. Our dogma insisted on the death of the author—our focus was on the text, as though it had been created in a vacuum. I was seduced by the latest fads in literary criticism, and wanted to fit in with the cool kids who populated that world. This approach to books is the antithesis of reading for pleasure—your mind has to be fully present so you can wrestle the book’s words into submission. You have to resist the pleasure of getting lost in the book.

Think about that expression—to get lost in a book. The French use the expression “s’évader dans un livre,” which translates to “escape into a book,” but since it’s a reflexive verb, it also means to escape oneself in a book. What exactly are we talking about? How do lifeless words come alive and how do we lose ourselves or escape from ourselves in books, and who or what takes our place? We have all experienced this, so it’s a banal phenomenon, but it is also very strange. How do those little black marks on the page cause our consciousness, or spirt, or soul, or mind, or whatever term we use to name the part of us that makes us us, how do those words cause us to be temporarily possessed by the author’s consciousness, or spirit or soul or mind.

Unlike my professors, Paul did not approach literature as a set of linguistic constructions to be decoded. And unlike me, Paul was never seduced by the latest fads (which, of course, made him all the more impressively cool). He often talked about how odd his profession was, that he would sit alone in a room hour after hour, day after day, year after year, and give birth to something that had previously only existed in his head. He fully allowed for its weirdness, while I, at the time, was hellbent on killing the author and naturalizing the book’s magic. In the end, however, Paul was right. Books can’t be reduced to linguistic constructions—they always exceed their verbal structures and what happens when we get lost in a book remains mystifying.

Paul was a storyteller—at the dinner table, in his films and of course in his many books. I learned from him—and I don’t mean that in a didactic sense, I simply listened and absorbed, and something shifted in me. I learned to resist the academic impulse to approach a book the way an anatomist approaches a dissection, dismembering paragraphs, segmenting syntax in order to diagnose, classify and explicate. Listening to Paul talk about books—writing them and reading them—changed how I read, how I want to read, how I think we should all read. Paul gave me permission—not explicitly—but permission nonetheless, to read again as I had as a child—to fully disappear into a story, into a world conjured in the mind of someone else, an outside world that once existed inside the author that then enters inside the reader. In other words, to surrender to the high strangeness of reading.

I have now come to believe that books are enchanted objects. Books, or at least good books, will always exceed our efforts to explicate them. The act of reading releases a book’s magic and produces a kind of telepathy, a silent communication with an author. Reading is a kind necromancy, a way to revive the dead.

I have not yet figured out what life will be like without the wonderful, breathing, funny, beautiful, embracing, brilliant, flesh and blood Paul who I have relied on to be there, in his body, for more than four decades. But . . . Paul has left us with more than thirty—maybe forty??—extraordinary books. As I was writing this, I pulled some of them down from the shelf, thinking I would find the perfect quote to include here today. But as I began to read, to get lost in his books, Paul’s voice was too loud, too present for me to listen to just now, and the cruel contradiction between his absence and that presence made me crumple up and cry.

I’m not ready yet, but what I do know is that those books are ensouled matter, they contain Paul, and when I’m ready, I will be able to open them and get lost in the worlds he created and I will commune, once again, with my beloved brother. We all will.

___________________________

CHARLES BERNSTEIN

I remember Paul playing his typewriter as if it were a piano, pressing the keys like Arthur Rubinstein playing Chopin. The clattering sound transported him to Austerland, a world his readers return to, with an avid fixation, the way lovers of Paris return to the Left Bank of their imagination. Paul’s instrument, to the end, was a manual typewriter. He refused to switch to electric or digital, the way a mountain climber refuses a chair lift.

I remember Paul calling on the telephone, even after everyone I knew switched to email and texts. He would leave a voice message if there was no answer and I remember one he left in Provincetown responding enthusiastically, and at some length, to one of my books. Paul called after he read each new book.

I remember a few months ago Paul called about fifteen minutes after I was to get to his house, wondering where I was, since I was always on time. I had turned left instead of right on Fifth and had walked a half a mile in the wrong direction before I realized. When I got the call, I was on his block.

I remember how much Paul loved Joe Brainard’s I Remember.

I remember the first time Susan and I met Paul. I think it was the summer of 1979. I can picture him walking down Station Hill Road in Barrytown with Daniel, who was one or two at the time.

I remember that Paul’s father in The Invention of Solitude (1982) seemed very much like my own father, but more vivid. I got to know my father better by reading Paul’s book.

I remember that Paul and I both suffered from the death of the oldest of our two children, Emma and Daniel.

I remember Paul sitting at our dining room table and telling me he planned to write a book about Stephen Crane. I remember looking at my laptop with him during that conversation. I remember thinking that Paul did not have a lot in common with Crane and then, when I read Burning Boy, I realized how immersed he had become in Crane’s life, as if he had taken it on as his own. I remember doing a video conversation with Paul about the book at his dining room table, with Susan and Siri as our very responsive audience.

I remember being stunned how Paul could recall even the most obscure facts related to Crane, the kind of things I can’t remember about myself. Sometimes I’d mention a movie but give the wrong actor or title. Paul invariably guessed what I meant and recounted the title, scene, actors, and director. We liked a lot of the same old movies and shared a love of many nineteenth-century American writers. I mentioned not so long ago that I had finally got ’round to Ulysses Grant’s autobiography. Paul immediately recited the opening passage and went on to describe what he admired most in Grant’s style.

I remember going to Paul’s studio in 1995 with Martin Spinelli to record one of the first of our LINEbreak radio shows. Paul talked about his supernal translation of Mallarmé’s unfinished poem A Tomb for Anatole, which Mallarmé wrote in the wake of his son’s death.

I remember Paul coming to the funeral for Emma in 2008 and how present he seemed to me at the gathering after at my mother’s apartment. I felt, still feel, he stayed with me through that still ongoing catastrophe. I remember, in the days after Emma died, returning to Paul’s translation of A Tomb for Anatole.

I remember riding with Paul from Penn Station to Princeton once a week in the spring of 1989 and 1990. The train was never crowded, so we were able to sit across from one another on facing benches. We talked to and fro. Paul had suggested to James Richardson that he hire me to teach poetry in the creative writing program; Paul taught translation at the same time. He left Princeton a few years later and never returned to teaching, while I started teaching in the Buffalo English Department during this time. I found it very odd that Paul had never been invited to speak at, or meet, any of the English department faculty. He didn’t even know the location of their building.

I remember riding on the Paris metro with Paul, Claude Royet-Journoud, Michael Palmer, Norma Cole, and Susan sometime in the 1980s. I remember Claude taking one photograph and Susan another so everyone would be in the picture.

I remember, right after Paul died, Claude sending me a picture of the cover of Paul’s first book, a collection of translations by French poets called A Little Anthology of Surrealist Poems and published in 1972 by Siamese Banana Press.

These past two months have been haunted by the death of friends. First it was Lyn Hejinian on February 24, then Tyrone Williams on March 11, Neeli Cherkovski on March 19, Marjorie Perloff on March 24, Jerome Rothenberg on April 21, and Paul on April 30. On May 4, David Shapiro died; he was born the same year as Paul, also in Newark; Paul and David were Columbia College classmates. I also keep thinking of the great Russian poet Lev Rubinstein, whose work I felt close to, though I met him only twice. Lev was born the same year as Paul and David. He was hit by a speeding car just across the street from his Moscow apartment; he died January 14. The timing of these deaths is a coincidence, surely; and yet, Paul turned coincidence into synchronicity. All but Lyn and Tyrone were aesthetically radical, nonobservant Jews.

Every hour hangs heavy, but each day is eternity. They say memory is a blessing. It’s also a curse that stabs you in the heart.

I remember sitting next to Marjorie, Jerry, and Paul on a 2004 panel that Stephen Paul Miller and I organized for the Center for Jewish History, in New York, on radical Jewish Poetry and secular Jewish practice. This was not a topic I came to readily; it’s a frame that fills me with an ambivalence that is inextricable from the topic, a productive resistance all of us shared. Last spring, Paul showed me a French study by François Hugonnier, focused on his work and Jerry’s, something hard to imagine coming from America, but a home run for me.

I remember walking with Norman Fischer on Third Street, just past the Gowanus, in the direction of Paul and Siri’s house, when Paul called to tell some bad news. I remember looking up and right, in the direction of his house, while we talked, as if that brought us closer.

I remember drinking bottles of wine while we smoked cigarette-size Schimmelpenninck cigars.

I remember listening to Paul’s bravura reading of 4 3 2 1 and then reading the passage in the book. I remember getting lost listening to the recording and then realizing I’d missed nothing when I went back to the book.

I remember being in China in 2007 with a scholar of Jewish American novelists, who was writing on Paul. Susan, Felix, and I were the first Jews he had ever met. We had a copy of The Invention of Solitude with us and, when I realized he didn’t know it, I gave it to him.

I remember the beautiful 1985/1986 hardcover first editions of The New York Trilogy, published by Douglas Messerli’s Sun & Moon Press. The first Sun & Moon book Douglas published was Shade, in 1978; that was my first book after the two I published myself. Paul’s three first-edition Sun & Moon books were stolen from the bookshelf in my apartment in the 1990s.

I remember Paul appearing at NYU with Pierre Joris, for the launch of the first volume of Pierre’s magnificent collected Paul Celan. I remember, before we moved to Brooklyn, it took Susan and I an hour-and-a-half to get from the Upper West Side to Pierre and Nicole’s in Bay Ridge, where we joined Paul and Siri for dinner.

I remember Paul saying we had to get out the vote to stop Trump in 2020 and again in 2024. I remember that he and Siri, and friends, cofounded “Writers Against Trump,” which became “Writers for Democratic Action.”

I remember Paul, in a red sweater, toasting his friends on his 70th birthday.

I remember writing to Claude that when I last saw Paul he was sitting in his chair in the library, relaxed and lucid. We had quite a long talk. I think it was April 15. He was putting his affairs in order, like they say, but that just became part of our normal course of conversation. We spoke last, on Wednesday, April 24. Paul said he was feeling weaker and not up for a visit—but that I should call again in a week when I got back from the country. He said how much he appreciated my visiting him so much the past year. I told him how much I loved seeing him.

I remember, a few years before the pandemic, going to a small local club near Paul’s to see his daughter Sophie and her band. There were only a few seats and I felt way outside my demographic comfort zone and realizing that Paul didn’t feel that way at all. I didn’t share his ease, but I loved it.

When it became too physically difficult for Paul to type, he handwrote a series of short letters to Miles, his newborn grandson. He would fax the pages to his assistant, who would type them and fax them back to him. It was crucial to Paul to see the typescripts.

I remember Paul saying that he wanted more time with Siri and Sophie, Spencer and Miles. He said that he wanted kaddish be recited at his grave—for the sound.

“Poetry was always his main concern, somehow,” Claude wrote.

Every hour hangs heavy, but each day is eternity.

They say memory is a blessing. It’s also a curse that stabs you in the heart.

I remember missing Paul.

___________________________

ANN LAUTERBACH

I knew him for many decades, intermittently after an initial intensity of connection, and now I am surprised at how deeply sad I am, as if an essential part of my personal ecology had ended. This must have to do with something that belies temporal constancy. In your life’s room, certain figures are always present.

He was most certainly acquainted with grief, but he was not a man of sorrows. He was aligned to his world, in the sense of agreeing with it, glad for its pleasures, and for his own industrious, singular acts of writing to and from it. These, in turn, were unmistakable, a certain pace and precision, incapable of rambling; as we know, the digressive for Paul Auster was in the service of possibilities, serendipities, rather than Jamesian dalliance or psychological complication. And so, also, he was personally direct, with a courteous, earnest interest and delight in company; beyond this affability was a rare capacity for devotion. One could not see him for years but then, in an instant, there was a live tissue of relation, as if friends were a kind of permanent syntax.

Someone told me once that Marcel Duchamp remarked he never did anything that didn’t amuse him, in what I take to be the French sense, not so much entertainment as concentrated, undistracted focus—deep play as a key trope of the imagination; the life of the mind. Paul Auster liked play, the game with (and sometimes without) rules. And because of this essential trait, everything that occurred was convertible to words, the fictive, however thinly disguised, and then, happily, the fictive made wonderful evolutions without ever abandoning its anchor; this was his conjuring trick, a kind of magic: to be simultaneously at home plate and the ball hit into the stands.

___________________________

ANDY MARTINO

Paul knew in August of 2023 that he might die sooner rather than later, but that wasn’t top of mind when he picked up the phone. He wanted to talk about Trey Cabbage.

“There is a player on the Angels,” he said. “I believe his name is Trey Cabbage! What a name! Cabbage!”

He let out a typical Paul Auster giggle. He had, after all, once published under a pseudonym a slim book called Love or Nothing: Tennis Matches We Would Like to See, which consisted entirely of lists with suggestions like “Digger Phelps vs. Robert Graves,” “Johnny Cash vs. Russell Banks,” and “William Gass vs. Thomas Paine.”

We had met eleven years earlier, when I was a young writer covering baseball. I’d noticed that the sport—usually his favorite team, the Mets—appeared in nearly all his books.

Why was this great author, whose works compelled us to think about the most profound themes, unable to shake off a game? Did he hold the key to understanding why baseball was worth our time and words?

I sought him out to write a piece about these questions. After a night in his library watching the Mets with his wife, Siri Hustvedt, and kicking around ideas, he walked me out to his stoop to wait for a cab.

Puffing on a thin cigar, Paul uttered the sentence that feature writers secretly dream about when interviewing people of whom they are fans.

“So,” he said. “Can we be friends?”

He meant it. We returned to that library—the room in which he later chose to die—many times to talk about the Mets, the craft of writing, and our families. He invited my wife, and read aloud to us in his musical voice passages from Twenty Days with Julian and Little Bunny by Papa, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s journal about babysitting his son.

“I’m not especially afraid. I’m seventy-six years old. This happens. What, am I going to be the only person who doesn’t die?”

He gave our son Collodi’s Pinocchio, the book central to his exploration of fathers and sons in The Invention of Solitude, which launched his prose career. With a warmth that somehow exceeded his brilliance, he went deep with us, and gave full access.

In the summer of 2023, the Mets were struggling yet again. This season had begun with a star-studded roster and championship aspirations; by August, the team had sunk to last place and traded most of those stars. They were trotting out an assortment of fill-ins and rookies.

One of those rookies, twenty-one-year-old catcher Francisco Alvarez, had made a strong impression on fans with his power and enthusiasm—but his streakiness at the plate and occasional boneheaded play worried Paul.

“Alvarez is like an overexcited puppy who shits all over the house and needs to be trained,” Paul said, giggling again. I laughed, too. From our very first meeting, he had shown himself to be as perceptive as a scout, though with more entertaining descriptions.

“So, how is your state of mind?” I asked.

“My state of mind is okay,” Paul said. “But I’m starting to stare down the abyss now. The great void.”

He paused, then added, “I’m not especially afraid. I’m seventy-six years old. This happens. What, am I going to be the only person who doesn’t die?”

He giggled once more at the absurdity of it all, then pivoted away from the Big Questions. He preferred to stick with the Mets. Or he preferred to stick with the Mets, even though we struggled to locate the meaning in these garbage time games.

“Oh, well,” Paul said, drawing in a deep breath and exhaling. “I still watch, because the season is dwindling.”

___________________________

MITCHELL KAPLAN

I’ve been a bookseller for over 40 years. I’m the luckiest guy in the world. I not only sell books that I love, but sometimes, I find myself in the presence of those who wrote them. And then, if I’m really lucky and the stars align just right, I can call those writers my friends.

My friendship with Paul developed just this way. One of the first books I championed in my just-opened bookstore was the 600-page The Random House Book of Twentieth-Century French Poetry. It was beautifully designed with Robert Delaunay’s Red Eiffel Tower painting centered on the dust jacket. The year was 1982, and I was so proud to announce to the world that not only were we the kind of bookstore that stocked copies of this dual-language edition with translations by American and British poets, but we were the kind that filled an entire window display with it.

Its editor, announced in large print right on the cover, is Paul Auster. In addition to editing, Paul also translated many of its poems. I spent hours being introduced to one poet after another, and when I read the bio on the inside flap, I learned that Paul wrote poetry and prose, too. I knew then that our bookstore and Paul would have a long relationship.

We did. City of Glass, Ghosts, and The Locked Room—the Sun Moon Press editions—were next. Our customers began asking for first editions of The New York Trilogy, and we did all we could to find them. In those days, before the internet, it wasn’t easy.

As the years went by, I devoured Paul’s work: the novels, screenplays, poetry, memoirs, translations, and essays. I loved that he edited Grove Atlantic’s complete Beckett. (We were both amused that Waiting for Godot’s US premiere was in Miami at the Coconut Grove Playhouse and that half the audience left at intermission.) I eagerly awaited those special books of his that were beautiful objects; we sold hundreds of The Story of My Typewriter, his collaboration with the artist Sam Messer, and Augie Wren’s Christmas Story with illustrations by Isol.

At some point, Paul made it down to Miami for a reading at either the bookstore or the Miami Book Fair; another time, I accompanied him to a screening of one of his films featured at the Miami Film Festival. I remember fondly a lunch we had in a Brooklyn restaurant with a group of writers that included him and the late Russell Banks. My memory places this during a long-ago ABA convention. I was in awe to have had a seat at that table.

I take solace in knowing that Paul’s voice will never be silenced.

We didn’t see each other often, but in a way that makes sense to any bookseller, his presence was always with me in the bookstore. His titles were on my shelves, and I conversed with him each time I recommended one of his works to a customer. By now, Oracle Night, The Book of Illusions, The Brooklyn Follies, and Sunset Park were new titles in full rotation on my recommended list.

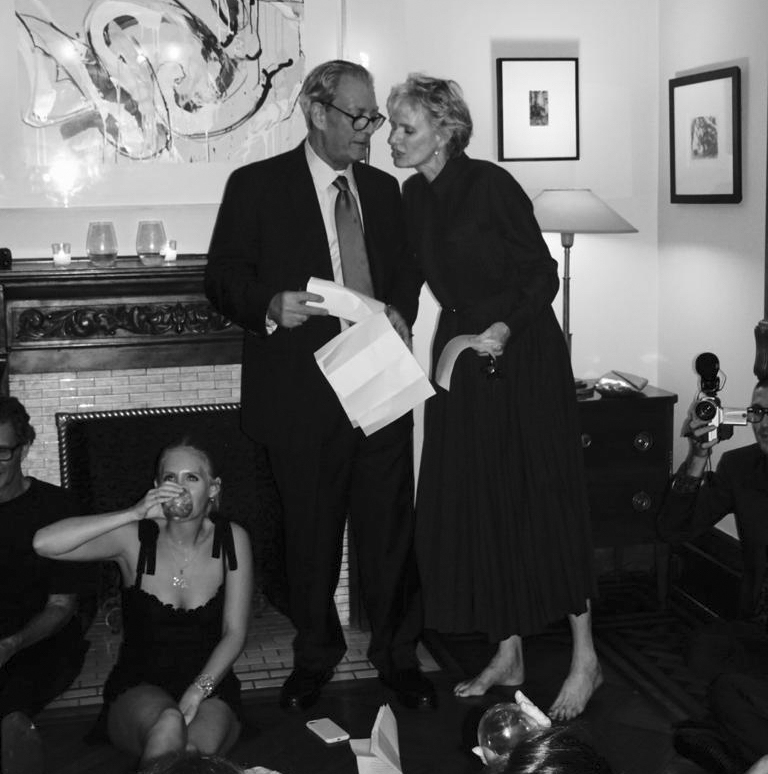

After much anticipation, 2017 brought 4 3 2 1, a revelation of a novel published in the same year Paul would be turning seventy. This called for something very special, so we arranged something special. Music, Magic & the Muse: An Evening with Paul Auster was a celebration of his new novel and of Paul himself. It all began with a reading by Paul and was followed by a stunning musical performance by Sophie and then a conversation with Paul and Siri. It ended with the great magician David Blaine performing an elaborate trick in honor of Paul, which was devised specially for this night. It should be a surprise to no one that magicians love the work of Paul Auster.

The night also revealed to me the incredible love that Paul, Sophie, and Siri had for one another. Paul took such pride in Sophie’s remarkable talent, while I was charmed by the teasing way Siri questioned Paul, and I was moved by Sophie’s assuredness. I would come to know these qualities that much more in the months and years to come.

In the year of the pandemic, 2020, I was asked to join Writers Against Trump, a group of writers who were meeting weekly via Zoom to brainstorm ways to ensure that Trump would be defeated. Paul, Siri, and Sophie were among the founding members. We met almost weekly and discussed the news, organized virtual events, and strategized to make even a small difference. Paul and Siri shared one of the boxes on my screen, and Sophie had her own.

All of us shared in the ups and downs of the next few years. After Trump’s defeat, we changed our name to Writers for Democratic Action and continued to engage in some good trouble. Our Zoom meetings continued, and Paul continued to write. Burning Boy: The Life and Work of Stephen Crane was published. Its almost 1000 pages are daunting, but its brilliance is only enhanced by its length. Following Burning Boy, Paul wrote the text to Sophie’s husband’s photographic essay on gun violence, Bloodbath Nation. Paul’s essay is the perfect complement to Spencer Ostrander’s powerfully quiet photos. There was also talk of a new novel, Baumgartner, and then news that Sophie was pregnant. Siri and Paul would welcome a grandchild into the world at the beginning of 2024.

Things changed last summer. Siri told us that Paul was sick, but the doctors were hopeful. It was a painful time for them, and the emotional roller coaster to come, I knew, would be taking its toll. They both, though, and Sophie and Spencer, too, found a way to navigate this new world with a kind of grace and openness and clear-eyed acceptance of what lay ahead.

Paul’s passing leaves me with a profound sadness. I’m most sad for Siri, for Sophie and Spencer, and Miles, who is not yet six months old. They have suffered a great loss.

I take solace, though, in knowing that Paul’s voice will never be silenced. Today, if you wander into our store and turn left into our poetry section, you’ll find a large stack of The Random House Book of Twentieth-Century French Poetry, edited by Paul Auster. Take a look. It’s really good.

_________________________

Paul Auster was one of the most acclaimed and beloved contemporary American authors. The selection below represents a fraction of the international coverage of his life and work.

ENGLAND

The Guardian (LINK)

“It is possible to cross a Paul Auster Platz and walk down a rue Paul Auster. Not many novelists have been so honoured. As a presence he was ridiculously handsome, worldly, generous, funny and, unlike most great talkers, a highly attuned listener.” –Ian McEwan

The Financial Times (LINK)

The New Statesman (LINK)

The Independent (LINK)

Statement from Paul’s editors at Faber & Faber, his British publisher

FRANCE

Le Monde (LINK)

“A key figure in American literature [and] one of the most brilliant of his generation. . . . Like no other, he knew how to retrace the lives of his characters, or his own, in all their breadth, contradictions, twists and turns, sometimes linked to apparent coincidences.”

Le Point (LINK)

“With Paul Auster disappears a brilliant, cultivated mind, a novelist who, over time, became more and more profound in his outlook on life, an American struck, in spite of himself, by the violence of his country. So many sides to explore in diving back into his remarkable body of work.”

Radio France (LINK)

GERMANY

Der Spiegel (LINK)

“In his continuous playing with the expectations of the reader, and in its style and content alike, The New York Trilogy belongs to the masterworks of postmodernity. Auster, whose books as it was so often pointed out were more beloved in Europe than in the USA, always continued to experiment in his writing, softening [literary] borders.”

Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung (LINK)

Frankfurter Rundschau (LINK)

SPAIN

El Mundo (LINK)

El Pais (LINK)

La Vanguardia (LINK)

BRAZIL

Folha de São Paulo (LINK)

“He used to talk about the force of chance, fatalities and coincidences; also of failure and the shadow of impending disasters; of the life of a writer, of banal and extraordinary events, of the absence of a father figure and of New York . . . Everything with a clear style, enhanced by the suspense characteristic of detective novels and by the influences of other writers such as Franz Kafka, Edgar Allan Poe and Samuel Beckett.”

ARGENTINA

INDIA

Indian Express (LINK)

“Auster does what an artist is supposed to—tell the story of a time through the story of people.”

Frontline Magazine / The Hindu (LINK)

SWITZERLAND

Blick (LINK)

Neue Zürcher Zeitung (LINK)

ITALY

la Repubblica (LINK)

Corriere della Sera (LINK)

24 Ore (LINK)

NETHERLANDS

De Telegraaf (LINK)

SWEDEN

Dagens Nyheter (LINK)

Göteborgs-Posten (LINK)

JAPAN