The following is the final installment of a six-part collaboration with Dirt about “The Myth of the Middle Class” writer.

______________________

As a former Catholic, I was raised to avoid public discussions of both money and oneself. Pride goeth before the fall, etc. As an American, money’s all I think about. Especially other people’s money, the real national pastime. It’s why you’re reading this now.

In my midwestern youth the notion of the artist’s life was imported from the coasts and often dinged up in transit: the pop L.A. cynicism of Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero and the novels of Bruce Wagner; the YOLO thrills of Dead Poets Society and On the Road. I still remember reading Kerouac’s “mad ones… desirous of everything at the same time” on a shift break at my summer gig as a country-club towel boy. It created a reservoir of fuck it! spirit that, since I was saving for tuition, had to be parsimoniously disbursed until I’d achieved some measure of adult stability. The irony wasn’t lost on me then, either.

Even F. Scott Fitzgerald, the golden boy of St. Paul, left for Princeton, then New York, Europe, and California. When I read him in ninth grade—“Winter Dreams” is spot-on about country clubs—my teacher felt compelled to mention the novelist died penniless.

So: creative pursuit equaled financial precarity and possible ruin. Transgression, too. I read Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting, then asked my aunt to drive us to Minneapolis’s indie theater to catch its film adaptation. (Yes, it was awkward; no, we don’t talk about it.) My reverence for literature was like John Cusack’s intimate fandom in High Fidelity. Michael Ondaatje was my Radiohead. (Radiohead was also my Radiohead.) This was as it should be. I wanted to be a writer in the way kids want to be astronauts.

As an American, money’s all I think about. Especially other people’s money, the real national pastime.

But there are wants, and there are needs. A period of economic chutes and ladders hardened my family’s pragmatism. And as a first-born American on my father’s side, there was the immigrant’s emphasis on work ethic, education, and striving for middle-class station. And yet. Adversity’s inevitable. The frictionless life, rare and boring. Francis Bacon wrote, “The best that can be said of fortune is that, as she uses no choice in her favors, so she does not care to uphold them.”

*

Three anecdotes.

In 2013 the novelist and short-story writer Karen Russell needed an emergency root canal, and she didn’t have dental insurance. As she told The Washington Post, “This was a bill that would have sunk me into a depression.” By a stroke of luck, Russell was informed that week she was the recipient of a MacArthur “Genius” Grant, totaling $625,000.

Donald Antrim also received a MacArthur that year. In a congratulatory note, his friend Jonathan Franzen joked Antrim finally had the means to afford his taste in clothes. (#relatable)

Between 2002 and 2008 I worked as a busboy, campus tour guide, janitor, and medical guinea pig. Upon graduation I found employment with a tech company that produced secondary-school curricula; my purview was French comprehension and English Lit. In one twelve-month period I lived on the same $36k salary in Seattle, Prague, and Manhattan. A night out cost, respectively, $50, $16, and $100—an arbitraged debauch.

*

Then I turned 30. I’d met the woman whom I’d eventually marry. (Thankfully, she’s much better with money.) I had a salaried position in publishing and a somewhat affordable apartment in Gowanus. In the hours before work, I’d noodle around with a novel manuscript, spending years rewriting the same 35,000 words. A personal hobby more than any kind of professional aspiration, and part of my lightly transgressive streak. It was fun working on what I thought was an unpublishable book before hopping on the F train to plan marketing campaigns for the new Jeffrey Eugenides.

Around this time I read Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. The Nobel laureate’s dense encapsulation of his work in behavioral psychology, much of it in partnership with the late Amos Tversky, relentlessly questioned the precepts of its academic fields and life in general. When we talk about sunk-cost fallacies, recency bias, or affective forecasting, we’re unconsciously citing Kahneman.

They found very unhappy people still tend to plateau. Everyone else correlates as you’d expect.

One of his most influential findings asked whether a higher income did in fact make one happier. Up to a point, Kahneman said; then it plateaus. You might get that raise but discover an $18 glass of wine isn’t much different from the $14 option. (I’m being reductive; nobody wants to hear a novelist talk economics.)

This had the seductive logic of the contrarian. I started to rethink my own correlations between income and happiness. I stress started to. In truth it would take about five years for Kahneman’s idea to truly take hold, and for my own material conditions to allow me to embrace precarity.

There were long conversations with my partner about what we were getting out of New York. Was it time to roll the dice? If not now, when? We talked a lot about risk tolerance. We auditioned Austin, New Orleans, both Portlands, then realized we couldn’t afford a house in any of them. We cast our net upstate and found Kingston.

You might get that raise but discover an $18 glass of wine isn’t much different from the $14 option.

I worked two full-time jobs for six months to clear my debts and build up savings. We got our house—with the dumb luck of low interest rates—and I spent a year commuting to Brooklyn twice a week. (Three hours door to door. I don’t miss it.) Then I went freelance and, for a period I euphemistically refer to as my investment years, cut my annual income in half. I’d never been happier. When nervous relatives questioned our decision, I’d refer to the Kahneman study, forwarding YouTube clips like an asshole.

Kahneman passed away in March. Among the obits and encomia was an aside about that income and happiness study. Turns out a flaw in the methodology had created specious data. Kahneman later revised the study in collaboration with Matthew Killingsworth. They found very unhappy people still tend to plateau. Everyone else correlates as you’d expect.

I was heartened to learn how wrong I’d been. That novelty, as an atheist, of finding a bedrock error in such a longstanding belief. Call it progress. I’ll discard the belief. Apologize to the relevant family members.

My risk tolerance is still high and under constant renegotiation. There are one-year plans and loose five-year plans. I’m never well-off, but I’m resilient. I flatter myself into believing my kneejerk empiricism keeps the transgressive habits in check.

A month ago we streamed Trainspotting at home, our dog at our side. My wife thought an old favorite would distract from the publication anxiety around my second novel. We made the TikTok salmon bowl, dimmed the lights, and switched our phones to airplane mode. We knew to finish dinner before the “Worst Toilet in Scotland” scene.

_________________________

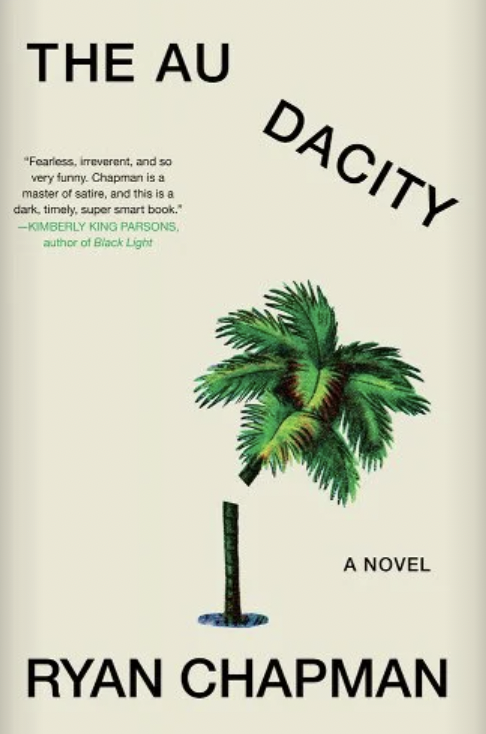

Ryan Chapman’s latest novel, The Audacity, is available now from Soho Press.