Every year, in the weeks leading up to the National Book Critics Circle Awards, the NBCC board members take the time to review and appreciate the thirty finalists, recognized in Autobiography, Biography, Criticism, Fiction, Nonfiction, and Poetry. Needless to say, these thirty books make a pretty good reading list.

This year’s National Book Critics Circle Awards will be held at the New School in New York City on March 21. In the meantime, see what the NBCC’s board members have to say about all of the finalists below:

Susan Kiyo Ito, I Would Meet You Anywhere: A Memoir

(Mad Creek Books, an imprint of The Ohio State University Press)

Susan Ito’s heart-rending and courageous memoir holds a secret at its core. At nineteen, as a transracial adoptee raised by nisei parents, she sleuths out the identity of her Japanese-American birth mother, defying laws that keep adoption records sealed. Their fraught first meeting is the beginning of decades of emotional ebbs and flows, as Ito’s biological mother cuts off contact with her repeatedly to maintain anonymity and avoid naming the man who fathered her. What sustains Ito: Marriage, motherhood, advocating for adoptees, and writing her own story. I Would Meet You Anywhere illuminates the complexities of identity, family, and belonging.

David Masumoto, with artwork by Patricia Wakida, Secret Harvest: A Hidden Story of Separation and the Resilience of a Family Farm

(Red Hen Press)

Secret Harvests limns the compounded tragedy of the Japanese internment for one family, when a cognitively disabled member, herself disabled via the racism of inadequate medical care–was separated and “lost” to the family during World War II. David Mas Masumoto uncovers the smallest thread of the story and achieves the seemingly impossible feat of reconnecting the lost family member whose story had been lost to racism but also family shame. In stark, stunning prose combined with Patricia Wakida’s evocative woodcut prints, Secret Harvests manages to take absence and turn it into presence, illuminating the hard-won resilience and joys as well as the darker corners of the author’s family history—and that of our nation as well.

Ahmed Naji, translated by Katharine Halls, Rotten Evidence: Reading and Writing in an Egyptian Prison

(McSweeney’s)

Ahmed Naji’s eloquent, and at times searingly funny, memoir of his time spent in an Egyptian prison, Rotten Evidence, reveals the importance of literature as a form of self-liberation. Naji was convicted of “violating public modesty” after an excerpt from his novel Using Life was published in a journal in Egypt. Naji recounts his experiences in detail, from the mundane daily indignities of incarceration to the camaraderie that develops between prisoners. The memoir is also an erudite literary text as Naji expounds on works of Egyptian literature, the Arabic language itself, and the limits imposed by successions of authoritarian governments. Katharine Halls’s lively translation captures Naji’s distinctive voice, by turns intellectual, enraged, sardonic; Naji comes across as someone who remarkably can always crack wise about his bully jailers and the ignorance of his government’s censors.

Safiya Sinclair, How to Say Babylon: A Memoir

(Simon & Schuster)

How to Say Babylon, Safiya Sinclair’s lyric memoir, is intimate, unforgettable and a shining example of why poets should write prose. The Eden of Sinclair’s Jamaican childhood is irrevocably altered under her father’s strict Rastafarian upbringing which first constrains, and then threatens, her life. Her poetic soul is matched by her resilience and perseverance and is the foundation of her courageous expressions of individuality and agency. Sinclair expertly weaves moments both harrowing and idyllic in a way that is candid, yet still generous to even those who have harmed her, which speaks both of her sensitivity and strength, and makes this memoir singular, universal and transporting.

Matthew Zapruder, Story of a Poem: A Memoir

(Unnamed Press)

Matthew Zapruder’s Story of a Poem pursues two questions simultaneously: what makes a poem work, and what makes a life matter. If those questions seem to belong to different realms of meaning, it is the quiet brilliance of this book to convince you of their interdependence. The story is of the creation and revision of several poems—messy, developing drafts included—and the equally messy process of understanding a child whose autism diagnosis wrenches the author’s first draft of parenthood into a new shape—all while the air outside darkens with wildfire smoke. It is rare to see the competing calls to creativity and care explored so literally, and with such urgency and tenderness, as they are here.

Jonathan Eig, King: A Life

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

In his sweeping biography of Martin Luther King Jr. Jonathan Eig recovers the civil rights leader from “the gray mist of hagiography.” Eig traces the arc of “Little Mike,” son of a Georgia sharecropper, to national prominence as an eloquent advocate for Black rights, as well as a crusader against the Vietnam War and poverty, all the way to Memphis and the Lorraine Motel balcony. Building on more than 200 interviews and recently released FBI files, Eig recently made national news by debunking a famous quotation about Malcolm X attributed to King, tracking fissures in the civil rights movement, and revealing King’s womanizing. With the velocity of a thriller, Eig evokes King in all his complexity, an imperfect but extraordinary man.

Gregg Hecimovich, The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts: The True Story of the Bondwoman’s Narrative

(Ecco)

The Bondwoman’s Narrative, written in the mid-nineteenth century and believed to be the first novel by a Black woman, caused a sensation when it was authenticated and published by Henry Louis Gates Jr. in 2002. Until now, however, the author’s identity remained a mystery. In this compelling new biography, Hecimovich combs through public records, handwritten diaries, almanacs, wills, and slave inventories and invites readers into his search, even the dead ends, to reveal Crafts as the former Hannah Bond, a child traumatically separated from her enslaved mother, who learned to read and write before escaping to the North and completing the book. Hecimovich convincingly demonstrates that Crafts’ writing was influenced by popular literature, in particular Dickens’ Bleak House, yet stands, sui generis, as what he calls “one of the most powerful imaginative records we have of slavery.”

Yunte Huang, Daughter of the Dragon: Anna May Wong’s Rendezvous with American History

(Liveright)

Daughter of the Dragon provides a riveting glimpse into the life of the beguiling actress Anna May Wong, one of Old Hollywood’s most recognizable faces. The book is the triumphant capstone to an ambitious trilogy: here, as in previous installments on Charlie Chan and the original Siamese twins (both NBCC finalists), Huang shines his spotlight upon a single, iconic figure in order to reveal a bigger picture. This dramatic account of Wong’s ascent to silver screen stardom—and subsequent descent into alcoholism and oblivion—thoughtfully illuminates the crucial role played by Asian Americans in the spectacle of modern culture.

Rachel Shteir, Betty Friedan

(Yale University Press)

In Betty Friedan, Rachel Shteir investigates the life, work and complex legacy of the trailblazing feminist. While Friedan remains respected for her contributions to early second wave feminism, her resistance to intersectional feminist work leaves her out of sync with contemporary feminist activism. The first biography of Friedan in a generation, drawing on extensive research and interviews with Friedan’s contemporaries, Shteir examines the ways in which Friedan’s early years growing up Jewish in the midwest and living in the shadow of her mother’s thwarted education, shaped her ambition, career trajectory and personal life. The determination that led Friedan to become a forceful national leader also closed her off from compromise and evolution. In this timely, important biography, Shtier makes the case that her impact remained crucial to social change in 20th century America.

Jonny Steinberg, Winnie & Nelson: A Portrait of a Marriage

(Knopf)

Jonny Steinberg’s deeply insightful, painstakingly researched Winnie and Nelson: A Portrait of a Marriage unmasks the Mandelas, sliding past their public mythos, and the simpler romantic narrative they told each other, to reveal the emotional labyrinth beneath. Steadily, through newly recovered material about the couple’s conversations – gathered by eavesdropping Afrikaner prison guards – Steinberg reveals how incarceration, torture, infidelity, and time itself, changed both husband and wife and their political stances. We’re left with a strong sense of the horrors they endured during apartheid, and the tenderness that remained between them at the end, even after they had inflictied pain on one another, and enduried so much cruelty and torture. With its exploration of two radically different approaches to apartheid, this beautiful biography speaks movingly to present-day struggles for racial justice.

Nicholas Dames, The Chapter: A Segmented History from Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century

(Princeton University Press)

1.) One of the most thrilling things a book of criticism can do is answer a question that you didn’t know you had. 2.) The question in The Chapter is particularly delicious, because you likely accept chaptering as a matter of course, without asking why books are split up. 3.) Nicholas Dames roams wonderfully from the Gospels to, in a particular highlight, George Eliot. He explores time, transitions, and the literal manufacturing of books. 4.) Dames is also a clear, lucid writer. 5.) The critical cliché in this case is true: after reading The Chapter, you will never quite read anything else the same way.

Myriam Gurba, Creep: Accusations and Confessions

(Avid Reader Press)

Creep is the very rare book of essays that could easily read as a single full-length study. Across her works to date (Mean, Dahlia Season) Myriam Gurba has developed a control over tone that lets her combine all of Creep’s elements—the creeping presence of Richard Ramirez, the itching fear of lice, anti-Mexican racism everywhere, cold Joan Didion beside the hot Los Angeles strawberries, Gurba teaching her high school students that that rape is about geography, not sex—into a coherent portrait in local sensibility. Creep is a tricky book that reads easy.

Naomi Klein, Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Naomi Klein has long challenged readers to look at the way we live from a slightly skewed angle in hopes of ultimately making the world more just. In this masterwork of storytelling, reporting, criticism, and analysis, she uses the idea of the twin, or the fun house version of our own world, to explore how truth works—or doesn’t—in today’s political and cultural climate. “It’s tough to live in a moment when so many truths that had been sold as settled suddenly become wobbly,” she writes. In this time of uncertainty we’re lucky to have her be one of our guiding voices.

Grace E. Lavery, Pleasure and Efficacy: Of Pen Names, Cover Versions, and Other Trans Techniques

(Princeton University Press)

Pleasure and Efficacy provides a groundbreaking study of the idea of gender transition in the modern era. Grace E. Lavery, a literary scholar and prominent activist, marshals a kaleidoscopic array of examples—from pseudonyms to psychoanalysis to The Silence of the Lambs—in support of her claim that sex change is possible. By turns playful and polemical, Lavery unpacks complex theoretical texts with an efficacy that is as astonishing to behold as it is pleasurable to read: a bold affirmation of the trans condition.

Tina Post, Deadpan: The Aesthetics of Black Inexpression

(NYU Press)

Deeply researched and refreshingly lucid, Tina Post’s Deadpan arrives as one of the most original and affecting aesthetic surveys in recent memory. Long consigned to the realm of play-it-straight humor, the book recontextualizes the act of withholding to taxonimize its origins and uses—specifically the tact it assumes when intersecting with blackness. Refusing to differentiate between “embodied blackness (or blackness as performed by black people) and symbolic blackness (or blackness in the cultural imaginary),” the author instead maps the many tributaries connecting the one to the other, illuminating how specimenization, perceived threat, gradients, and the tension between excess and absence evolve and get repurposed by black and white artists alike.

Teju Cole, Tremor

(Random House)

In Cole’s triumphant return to fiction, the critic, novelist, and photographer finds new possibilities for autofiction. The book is dense with digressions on art and colonialism from Tunde, the Harvard-photography-professor narrator (one chapter takes the form of a lecture implicating an audience of museum patrons in the legacy of cultural appropriation). But it’s more than a vehicle for ideas. Rather, the story is about what these ideas mean for Tunde as he considers his own degrees of privilege and the exploitative nature of photography while reckoning with memories of growing up in Nigeria and of an old friend whose occasional presence adds to Tremor’s elegiac and haunting quality.

Daniel Mason, North Woods

(Random House)

A house surrounded by an apple orchard in Western Massachusetts provides the setting for Daniel Mason’s ghostly masterpiece. Told in vivid overlapping stories, spanning from the Puritan colonial era to the future, the novel lays bare the poisonous American obsession with property and its deleterious effect on ecological succession. Beauty, humor, and violence surface in the lives of the house’s colorful inhabitants over the years: spinster sisters, ambitious farmers, a painter harboring a secret desire, and a troubled young man, among others. The bold accordion-like structure of North Woods (letters, songs, and poetry are mixed with conventional narration) traces an erosion of humanity even as its players yearn for a better future.

Lorrie Moore, I Am Homeless if This Is Not My Home

(Knopf)

Lorrie Moore’s I Am Homeless If This Is Not My Home is hilarious and beautifully written, which is no surprise coming from Moore, whose short stories and novels have delighted readers since 1985’s Self-Help. The surprise is in the absolute boldness of this novel—a zombie road trip is interspersed with letters from an innkeeper written just after the Civil War. Even more astounding is the beating heart of the work—amid the chaos and contortion of the plot, this is a tender and poignant examination of grief, loss, and memory. It’s a wonderfully elusive book from a master of form, packing multitudes into just under 200 pages.

Marie NDiaye, translated by Jordan Stump, Vengeance Is Mine

(Knopf)

At the heart of Marie NDiaye’s hypnotic and ingenious literary thriller is a sensational legal case: Maître Susane is hired to represent a wealthy man’s wife, who has been accused of murdering the couple’s three children. Susane, who has never tried a murder case and is of a working-class background, believes she met Principaux, her client’s husband, decades earlier when she was ten years old. NDiaye, who began publishing her slippery and original fictions three decades ago at 17, entwines subtle mysteries with depictions of harrowing violence. Elliptical and lyrical, Vengeance Is Mine amounts to a disquieting exhumation of the past and its tight, invisible hold on the present.

Justin Torres, Blackouts

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Justin Torres radically experiments with the biographical fiction genre to stunning effect. Structured like an exquisite nesting doll of stories, the novel follows the arrival of the young exhausted narrator at the Palace, a convalescent home where he has come to help Juan finish his erasure project involving Sex Variants, a real-life 1941 collection of anonymous interviews with gay and lesbian people. Contributions by queer journalist Jan Gay were uncredited, and Juan and the narrator work together to highlight this unjustly forgotten legacy, as Juan prods the narrator for details of his own clouded past. Blackouts is a tour de force of desire and reclamation.

Roxana Asgarian, We Were Once A Family

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Asgarian draws on her background as a Houston court reporter for her astonishing debut. The book is a meticulous, harrowing, and deeply empathetic investigation of the story behind the deaths of a married white Portland, Ore., lesbian couple and their six Black Texas-born adopted children from a cliffside car crash in Mendocino County, Calif., that was ruled a murder-suicide. Asgarian provides a blistering indictment of the Houston family court, child protection agencies, and adoption agencies that wrest children such as the victims away from their birth families, and of the media’s focus, in looking for answers to explain the crime, on the psychology of the adoptive mothers rather than the structural conditions impacting the children’s birth families.

Kerry Howley, Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs

(Knopf)

You might not expect to be moved by a book whose title refers to a conspiracy theory about how Monster Energy Drinks are actually vehicles for Satan. But Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs is a clear-eyed and nuanced accounting of the ways in which our modern security state reduces human beings into little more than unending terabytes of data. Kerry Howley interprets such data in a way that is distinctly human and deeply generous; she distills small, telling details from a larger story about conspiracy theorists and whistleblowers and everyone in between, while still allowing her narrative to meander and digress in surprising and revelatory ways.

Dina Nayeri, Who Gets Believed?

(Catapult Books)

In Who Gets Believed?, Dina Nayeri (The Ungrateful Refugee) collates data from real situations where the stakes of personal credibility are high and their outcomes apparently arbitrary. She connects a refugee whose story is rejected on absurd grounds to her own skepticism, as a Christian child refugee in the United States, of the thrashing antics of the girls around her in church. Nayeri exploits her heterogenous life experience (a management consultancy interlude is among the book’s oblique surprises) to compose a work something like philosophy, one that forces old conceptual questions back into conversation with their crucial roles in daily life.

Jeff Sharlet, The Undertow

(W. W. Norton)

In “The Undertow: Scenes From a Slow Civil War,” journalist and author Jeff Sharlet takes readers on a chillingly urgent tour of Donald Trump’s America. Sharlet gives us much more than soundbites as he immerses himself in Trump rallies, a men’s rights conference and a prosperity Gospel megachurch, and as he talks in depth with conspiracy theorists, white nationalists and acolytes of Ashli Babbitt, the woman shot on Jan. 6, 2021, as she tried to break into the U.S. Capitol, “transformed” after her death, Sharlet writes, into “yet another flag, like a new tarot card in the deck of fascism.”

Christina Sharpe, Ordinary Notes

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

From the glimmering mosaic of Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes emerges a luminous vision of a mind and life, “ordinary” only in the sense that it contains the matter of her daily reckonings, the memories of an extraordinary mother, the “antiblack notes” that have impinged on her and all Americans’ experience of life, and the lovely counter-notes—the lessons, the art, the courageous voicings—that create a new understanding of the world: “All of our renewed power to refuse the concentric senses of the ruinous.”

Saskia Hamilton, All Souls

(Graywolf Press)

In the exquisite and profoundly affecting All Souls, completed just before her death, Saskia Hamilton wonders if writing can be “a form of practice or of preparation for death” and answers with a meditation on all the things that mattered deeply to her: family, memory, art, and literature. What she creates is something surpassingly rare, a kind of auto-elegy that is all the more moving for being devoid of sentimentality and self-pity, a vision of a brilliant mind mulling over the shards of what she knows, trying to see into and past death, not to vanquish it but to capture life, “caught in the far gone far alone glance / of mortality.”

Kim Hyesoon, translated by Don Mee Choi, Phantom Pain Wings

(New Directions)

With stunning originality and audacity, Kim Hyesoon creates an alternative imaginative universe that reflects a consciousness battered by and overcoming life’s agonies: the aftereffects of war and dictatorship, the oppressions of a patriarchal society, the death of a father. In Don Mee Choi’s powerful translation of Phantom Pain Wings, the presence of the multi-faceted creature called “bird”—nemesis, inner daemon, doppelganger, muse—reverberates outward until, as with all great poetry, it assumes the fragile, mortal proportions of art itself: “I thought about bird flying freely in the ruins / bird that will fall if I don’t keep writing.”

Romeo Oriogun, The Gathering of Bastards

(University of Nebraska Press)

“Perhaps exile is us running through history // I have not to give, even my body is empty of a country.” So begins Romeo Oriogun’s breathtaking The Gathering of Bastards, a multitemporal saga of migration charted against journeys of queerness and subsequent exile. Nigerian-born Oriogun’s poems are rooted between boundaries, engaging with war and dictatorship while employing a lyricism that instills a sense of magical possibility. Despite repeated losses, Oriogun pens an expansive dream of freedom: “Having known that there is no home apart from terror, / I lend my voice to our survival. I demand a wild life.” Through the wild lives of these poems, Oriogun offers readers a profound communion.

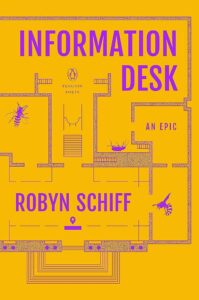

Robyn Schiff, Information Desk

(Penguin Books)

With a sweep that encompasses the intelligence, eroticism, and callousness of the Western art canon, Robyn Schiff’s Information Desk presents a mundane setting for the epic: the eponymous desk at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the poet worked in her youth. Yet for all its cataloguing of the indignities of the role, Schiff’s epic poem refuses to stay grounded, taking readers on a whorl through art history, her personal relationships, and the behavior of parasitic wasps. What unites these topics is the symbiotic relationship the subjects have with their muses (or hosts). Like the book itself, these relationships are sometimes beautiful, oftentimes brutal, and alluring in their observation that not all monuments are erected on equal footing.

Charif Shanahan, Trace Evidence

(Tin House)

“Dear one: I was trying to enter my own life, I felt outside my own life. I was / Looking, trying to find a door.” In the searching intimacies of Trace Evidence, Charif Shanahan uncovers his own hard-earned definitions of identity amidst the dislocations of a life at the margins–postcolonial, queer, biracial–in order to inhabit life on his own terms. A near-fatal accident in Morocco, the home country of his mother, becomes the focal point for gorgeously frank and delicate lyrics that both query and implore: “Is it possible my function is to hold / All the intricate, interstitial pain / And articulate clarity? / Tie a boat to my wrist, I sprout wings.”