This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Writing is hard work, and often frustrating, unfruitful, or downright excruciating. I spend a great deal of time avoiding even thinking about sitting down to work, and therefore, necessarily, I spend another significant amount of time persuading myself I ought to do it. And how awful and frustrating that this is the case! I love everything about books until it comes to writing them, and therefore the business of writing is reminding myself that there is something of interest in a story or an idea I can latch onto, like a tick. Or perhaps I’m more like an oyster, a reclusive and unprepossessing blob who needs a bit of grit, an irritant or a problem that I can begin to lacquer over.

The times when I’m happiest while writing are those times when I’ve invented a problem or a complication that needs solving. This might be a decision about an approach to character, or the kind of language or tone I’ve decided I want the story to inhabit. It could be deciding on a form, a word count, or a genre (or combination of genres), or a revelation or resolution that I want to hide from the reader as long as possible, while also laying down breadcrumbs that lead up to that moment which, in hindsight, have set up that turn.

In workshop I often begin by asking new writers to make a list of as many things that most delight them in narrative, so that in turn they can have in mind ways to introduce delight in their own work which is often, in beginning, daunting and un-delightful. After all, we must be our own first readers, and the possibility of delight or pleasure keeps us anchored to the work that we must do. But surprise and the chance of discovery are other tools, and worth cultivating.

The list below is one I’ve been adding to over the past month. I think of these as interruptive or transformative prompts. Some I’ve used in the past. Others I’ve lifted from books I’ve read, imagining how I might use them.

The times when I’m happiest while writing are those times when I’ve invented a problem or a complication that needs solving.

Not every story requires a transformative prompt. Not every writer needs to rely on strategies like these. But if your own work feels, at any stage, stale or familiar to you, or as if the path is so clear that there’s little point to going down it, perhaps try one of these—or even two or more in combination. You might pick one of these and apply it to something you’re already working on, or begin a new story with one of these in mind. You might also make your own list of ideas that might helpfully complicate your narrative in some way. If you’re part of a workshop you might make communally make your own list.

The last sentence reverses or subverts the meaning of the first sentence.

To be written in one hour or less.

An animal talks.

All characters are talking animals.

All characters are to be conceived of as talking animals, but this is never mentioned by the writer or the text of the story.

Epistolary story, written in haste.

Uses the language and imagery of fairy tales, but is not a fairy tale.

A story annotated with footnotes by someone who is a minor character in that story.

Language which calls attention to itself. A wall of rose briars. A thicket, entanglement, armature, incantation.

Disordered time.

The story told as plainly as possible.

A death which the narrative was not meant to encompass.

A palindrome.

The action moves in and out of a hospital, but the story is not about the cause.

The story presents a set of rules for living. Some of these to contradict.

A narrator who hates the reader and addresses them with malice at heart.

Some words, crucial to understanding of story, are blocked out.

The numinous domestic.

Continuous point of view shifts.

Meaningless sex—a feast—hedonism—indulgence of various sorts, including of language.

The style of the story to be at war with its genre or substance.

Two stories, written in tandem, in alternating sentences.

A baby is present in every scene—this baby can be used to surreal or realistic effect.

Made up words, used authoritatively, without explanation.

A character, either minor or off stage, to be treated as an almost supernaturally threatening presence, but nature of threat is never explained.

A character appears to be operating according to the rules of a genre which is not the genre of your story.

A story which embraces metaphorical language, embarrassingly so.

Use of the fantastic in such a way that it stymies metaphorical meaning as much as possible.

A story which is directly in conversation with a story by another writer. This may or may not be evident to the reader.

A matryoshka story, told at least three times, each time condensed and changed until the last version is one sentence. This sentence may be at odds with what the reader thought the story was about.

The natural world interrupts and overgrows the narrative.

The story to contain drawings. These need not be good.

A sentence to repeat throughout the story.

The story refuses to be understood. There is something else that it wants of the reader. Possibly of the writer.

_____________________________________

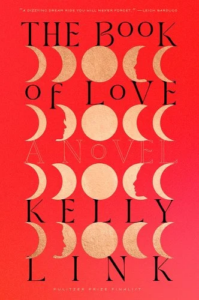

The Book of Love by Kelly Link is available now via Random House.