Forty years ago, Padgett Powell’s erudite coming of age novel Edisto was released and introduced readers to a 12-year-old literary prodigy named Simons Everson Manigault. Following an acrimonious separation between the “Duchess” and the “Progenitor” (Simons’ parents), the young boy finds himself living in the Manigault summer home in Edisto, South Carolina while his mother descends into alcoholism.

With his domestic reality crumbling to its foundations, Simons spends most of his time at the Baby Grand, a Black nightclub whose patrons take a shine to the young truant. When the Manigault maid’s biracial grandson arrives in Edisto looking for his mother, Simons names him “Taurus” and the name sticks. The unlikely pair develop a friendship, ushering Simons into the world of mid-century American race relations, the sexual revolution, and the infelicitous vortex of confusion that is puberty.

In addition to celebrating Edisto’s milestone anniversary this year, Powell will be releasing Blasphemy and Other Ancestors (Gordon Hill Press), a collaborative book co-authored with myself, Darius James, and Lee Henderson about the tag end of existence and the abasements that memory holds in store for characters living outside of their time.

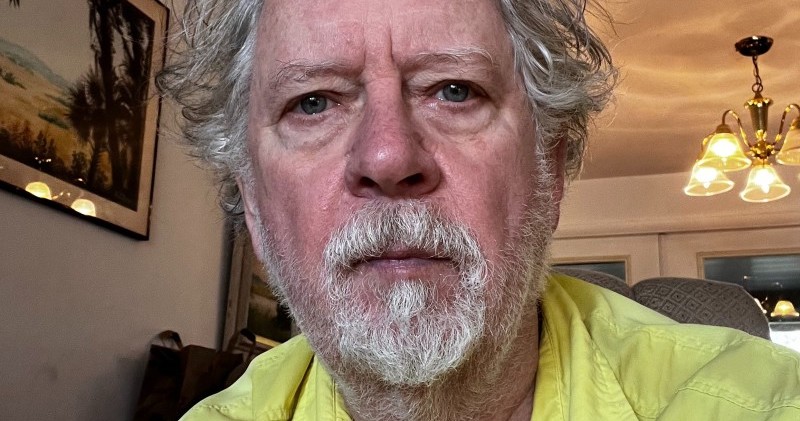

I corresponded with Powell to discuss the relationship between cornpone and Flann O’Brien, the “rotten taste of America” informing literary culture, and building a career around the “fey interface between believing in the South and making fun of believing in the South.”

*

Jean Marc Ah-Sen: What was the central attraction of writing Edisto, a bildungsroman that explored Black and white race relations in the South? Why do you think so many writers feel compelled to start their careers writing about emotional and intellectual maturation, and to which characteristics of the coming-of-age novel do you attribute its pride of place among a broadly defined readership?

The attractive characteristic of a young narrator is the absurdity of it and the license of it.

Padgett Powell: Let me warn us that these questions are too recherche for me. I now lack the juice to fuel the bluster to conceal that I am a simpleton.

A professor in college was roundly pregnant on a Monday, absent Wednesday, and giving her lecture on “The Miller’s Tale” on Friday with the baby on her hip. I thought “What if that little bastard picks this stuff up and knows Chaucer when he’s five?” My own brother had a good mouth on him, there was already the mother in front of me—the novel was there for the writing. The cerebral cogitation was done. Just Strunk & White some sentences and connect them head to tail and throw in everything you’ve ever seen or heard. Done.

You don’t write about “emotional and intellectual maturation.” The attractive characteristic of a young narrator is the absurdity of it and the license of it. Huck Finn is a 14-year-old uneducated antebellum white boy in Mississippi? Huck Finn is Mark Twain being as smart as Mark Twain was. Huck Finn turns him loose. The absurdity of the proposition is like lightning.

JMA: Edisto explored the legacy and aftermath of the reconstruction era all the way into the 1960s. Donald Barthelme in particular praised you for writing about things readers had never heard before between Black and white characters. Did you have a sense that books written about a similar milieu before or around the time of Edisto’s publication were characteristic of a mealy-mouthedness when it came to racial politics?

PP: I am innocent of anything written along these lines or the spectrum of candor in them. Because I was arrested for my underground newspaper Tough Shit in high school and the principal sent it to my college to dematriculate me from it, and I had as a result narrated the events of my arrest to four eminences at that college, the Dean of Men there put me in a dorm room with the odd Black boy out because he figured I was radical enough to be liberal enough to handle early integration.

“I didn’t want some redneck to eat him up,” he put it to me three weeks into the semester. I said I wouldn’t. Jinx took me to his bar—it’s in the book, verisimilitudinously. I saw some low country Black life behind some doors. We’d had a long-term maid, a complicated woman—in the book as Theenie, verbatim. I saw some mullet fishing in Florida where a woman berated a fellow for his sloth; “You so slow, no wonder your wife left you.” His name was Buckwheat, a name I could not alter or drop, as prudence would have suggested; she called him Wheat, and when he said, “She din’ leave me, she died,” the woman yelled, “The ultimate leff!” If these are things not heard before, it is only because no one has listened and written them down. You could not publish them in America today because of liberal-editing racism.

JMA: Twelve years after the release of Edisto, you returned to the world of the Manigault family with Edisto Revisited. What were your motivations for dropping back into the land of mullet fishing, moonshine, and professorial mores during Simons’ university years? Did you always have a sense that there was more to Simons’ story that warranted revisiting, or was there some realization that came afterwards that signaled the attractive possibilities of the story continuing in a sequel?

PP: I had no sense of more to tell, certainly no sense that more was merited, but it was what I could write at the time and I wrote it. Let me lean us up on Flannery O’Connor, our late racist goddesshead: “When I told you to write what is easy I meant what is possible. It is never easy.” If I have misquoted her, it is because my brain has little spots of something in it.

JMA: Your career has been described as participating in the American Southern literary tradition. Was this an association you felt honored by, or perhaps something that you were suspicious of? Do you think that writing embodying the principles of the American South needs to be constantly evolving, or is it something that needs to be carefully curated, and whose boundaries must be clearly defined, in order for it to endure?

PP: It might be fun to tear it all up after the Jews Will Not Replace Us boys in their khakis protest, holding copies of Absalom! Absalom! upside down in the style of Trump with his Bible with duped General Milley at his side. It could all go into the big smelter with the Bobbie E. Lee bronze. But then some smartass would invent another plantation house, another confederate widow, another lost utterancer of the not yet lost cause.

I have made a career of dancing without dancing in the fey interface between believing in the South and making fun of believing in the South, which is why no one has ever heard of me. It’s a lame-ass position. The proper term is chicken-shit.

Who would object if clubists wanted to shove you into a cubbyhole with Faulkner and O’Connor and their queer son Tennessee and too straight son Walker and what-litter-is-he-from son Don? Not I. And my God, Barry Hannah got more out of the whiskey oracle than anyone dead. I do not like the sentimental blood-and-grits crowd and I do not like the apotheosis of Story as Panacea, the from-farm-to-porch menu. Cornpone. No.

Southern writing, not often actually defined, means a deep-down knowing that people are beat to shit. An earnest suspicion of earnestness, a recognition and denial of whippedness. I am now spinning cornpone myself. End of the foregoing. Let’s go read some Flann O’Brien. Those brothers are whipped for real.

JMA: The book that you are perhaps most known for is The Interrogative Mood, A Novel? which is entirely written in the form of meditative questions—“If you were to participate in a spice war, what spice would you fight for?” is my personal favorite. Did you conceive the book as a rascally wedge that could be placed between experimental and commercial fiction? Or was the book perhaps an effort to assert the primacy of artistic questioning over the fatuousness of shopworn opinions?

PP: You continue to try to flatter. But this is sharp flattery. It moves me to pomposity: experimental fiction means no more or less than fiction whose central thrust in not made-up people doing made-up things. Let’s call that MUPDMUT. With some liberty, Mupdeemut. Experimental fiction may of course have Mupdeemut in it, but not as the thrust of it—something beyond our believing in Mupdeemut is at hand.

When Hulga’s leg is stolen by a Bible salesman, we are to believe it. When our friend Colby has gone too far and is to be hanged, we are not to believe it. We have the pleasure of seeing Colby in his anguish, but we have a larger or smaller pleasure of distraction from the dictate to pretend this horseshit actually happens. That is the “experiment.”

Does the imperative to not believe exceed the pleasure of the imperative to believe? Donald Barthelme believed it did if the writing still contained emotional payoff. O’Connor would have said, did say, to hell with it. “If [the Devil] is only a symbol, to hell with it.” The imperative to believe is at one level rather childish, as in Once upon a time… This is why Coleridge had the wit to call it a “suspension of disbelief,” not precisely an imperative to believe. What an upgrade to be told, “Don’t believe this, you morons.” What you do, mischievously, is believe more. At which point the “experiment” has succeeded.

The Int. Mood goes way too far, in Colby terms, and dispenses with Mupdeemut altogether, except for the occasional Jimi Hendrixes being offered a BLT as he affects to play you a tune. There is no history of intellection in its conception or intent and no prefiguring in its execution (Huck Finn shows you prefigurating for a book like Edisto).

I received an email from a colleague who wanted me to talk to the Dean that opened, “Is it time for us to have a chat with the dean? Are we remembering what was promised us, last spring, at lunch? Are we going to let history repeat itself?” I suffered pique at this and wrote back, “Are your emotions pure? Are your nerves adjustable? How do you stand in relation to the potato? Should it still be Constantinople?”

The pleasure in this was extreme. I thought how funny it would be—Reply All—for her to receive 600 of these questions, and wrote 600 of them, and then could not stop and wrote 142 pages of them. I saw the “rules” immediately, using her model, but exaggerating the forces. Relieve the silly with the grave, the arch with the colloquial, perfect the overt non-sequitur, watch rhythm, let each sentence deliver its impact—a stonking of someone who would presume write your ass with questions as annoying as they were. Marvelous fun, therapeutic because I was fair exercising some deep contours in my shallow brain, and I felt fine every time I wrote a batch of these things, which I began to liken to thousands of redundant missiles like those we have in our nuclear silos.

JMA: Your prose tends to be voice-driven and characterized by a kind of malapert urbanity. Can you talk about how this stylized way of writing developed, and if it was an artistic response to things you were reading (whether inhospitably or with a deal of enthusiasm)?

PP: I am ignorant of “malapert” but I do get “urbanity.” Here is as an almost certainly impertinent answer that I do not intend to be impertinent: I learned to write the English I have written by taking three years of Latin, in the putatively desolate educational backwater of Jacksonville, Florida, ending in the tenth grade translating The Aeneid. I was in homeroom sitting with Allen Collins of Lynyrd Skynyrd. We was gettin’ it. We did not know we was gettin’ it.

JMA: Does the prose voice that you adopt develop in parallel to the thematic concerns that you will tackle in a given work, or does it emerge as a result of other considerations?

PP: It emerges with no consideration for anything but the next correct word.

JMA: The destiny of all books is to become unmoored from the time which birthed them, and as new readers discover them, their relationship can become not just tinged, but entirely defined by a sense of presentism. You spent a large part of your career teaching at the University of Florida Creative Writing program, and I’m wondering how you would address this reality when and if it occurred in the classroom? Is there, in point of fact, a “right” and “wrong” way to read?

PP: We read formative work asking only what might make it better, by which I meant power in the writing. As I came to the end, the students seemed to have been coached toward a new kind of “better” that meant what was less offensive, and the offense was a multi-headed, surprising beast. One student got in trouble with others when he created a character named Phone Ho. I was mystified by all this and got away rather than try to breast the tide.

I was not going to be able to teach writing, if I ever had taught it. I was turned in for use of the phrase “tsunami of inclusivity.” The phrase was examined for “racial content.” It was judged to be empty of racial content. A prior student suggested I use “politicalicity” as in “tsunami of politicalicity” and I paid him $20 for the word, inserted the phrase, and retired. Please see my students Kevin Wilson and Chris Bachelder, and Kevin Canty and Chris Adrian. There are more. These are just my Kevins and my Chrises, as Trump would put it. God are we doomed.

The destiny of all books is to become unmoored from the time which birthed them.

JMA: Your latest work will be the novelette “The New Book” in our omnibus book Blasphemy and Other Ancestors. Your offering concerns a man of letters taking on an assistant and training him in the righteous arts of romance, but it also features a metafictionally aware narrator playing against a hypothetical reader’s reservations about events unfolding in Florida. I’m curious if this was a way to express frustration with the sensibilities of modern readership or literary criticism?

PP: I think not. What I recall was writing a fairly comprehensible sketch in the South-satire genre, kind of my schtick, getting tired of my schtick, and for relief sliding into something untenably surreal in which even I could not keep straight what I was talking about. So I shet that thing down. My hero turned into Ted Turner, and Monteagle, Tennessee became the Philippines in WWII, and a girl at Walmart turned into Vanna White and I was doomed.

JMA: In an industry that routinely heaps indignity after indignity on its practitioners, what has been the most startling development that you have encountered in recent years while releasing your books? Was it an issue arising as a matter of course from past frustrations, or did it spring from some unprecedented corner of the industry?

PP: It sprang from the unprecedented corner of my own publisher. My book Indigo had been edited and copyedited by two astute, eminent editors, was set to roll, when a “sensitivity editor” was brought in because someone in marketing at the house was not “comfortable representing the book.” (For the record I never saw any evidence that anyone represented the book)

The sensitivity editor, who I suspect was given four times the money I was given for the book, fell to with their sensitivity broadaxe. In a long true account of a dust-up at a restaurant in old Austin, not new Austin, a Black man on my roofing crew came to my defense and knocked out a white restaurant manager, who was at the moment presuming to assault me. Willie had noticed that the manager had Black back-up and felt I should too. “Old Padge need him some brothers too,” he would explain later.

The piece was essentially a portrait of a hero, Willie Ebert Brown, in a terrain of racial relations that had hope in it. The sentence that announced the Black back-up for the manager was this: “A sturdy-looking Black guy came out of the kitchen.” This is choice low fruit for a sensitivity editor. “Objectifying description,” she wrote, “that may invoke associations with slavery.”

I should have desisted publishing the book, but I am a chicken-shit person and I really wanted a book with a beautiful photo of an indigo snake on its cover. My celebration of Willie was thrown out; my invocation of slavery (to which who objects, its absurdity aside?) was one of a hundred other crimes in the piece. Liberal racism had its way: remove racism by removing race.

There is not a person of color in my book except a very positive small tribute to Barack Obama as a tool by which we might argue the French can slow their roll about how racist we are and they aren’t. How that was not deemed racist is a wonder, because it somewhat is. It’s not a wonder: liberal racism is a photo-negative argument. I apologize for this rant. Chicken-shit and now tired too.

JMA: For decades now, readers and writers alike have speculated about where the future of literature is headed, with some espousing the belief that literary fiction in particular is going the way of opera and ballet. I think it could be argued that anything betraying a high literary sensibility is already beholden to blue-blooded patronage and sponsorship, whether we are talking about arts grants and awards bodies or content subscription models like Substack or Patreon. Do you think that literary fiction can find mass appeal among readers or has its place always been in contradistinction to an upmarket reading sensibility?

PP: Does “an upmarket reading sensibility” mean people who buy books at the airport? I confess to feeling loose reading this question. Let’s do a loose answer: a really good book, with anomalies here and there, will not sell well to a mass American market. If you make money here, you have done something wrong. It’s the rotten taste of America, the same force that explains a Trump. We have problems way larger than a poor good writer and a successful conman at large in Washington.