My new poetry book, The Shining, attempts to tackle many feelings characteristic of our current moment. The fear and isolation that we’ve all undoubtedly felt as we’ve battled the coronavirus pandemic over the past few years is merely one.

I remember early moments of our 2020 lockdown feeling as if I were trapped in The Shining movie, and that my old life of going outside was a distant memory. It wasn’t snowing outside my window, but the invisible forces of the deadly virus created a kind of storm that was unsafe to venture out into. As Bernadette Mayer’s poem “The Way to Keep Going in Antarctica” states: “Nothing outside can cure you, but everything’s outside.” I felt that longing for what was beyond my walls, and yet I couldn’t help but feel that everything was forever gone.

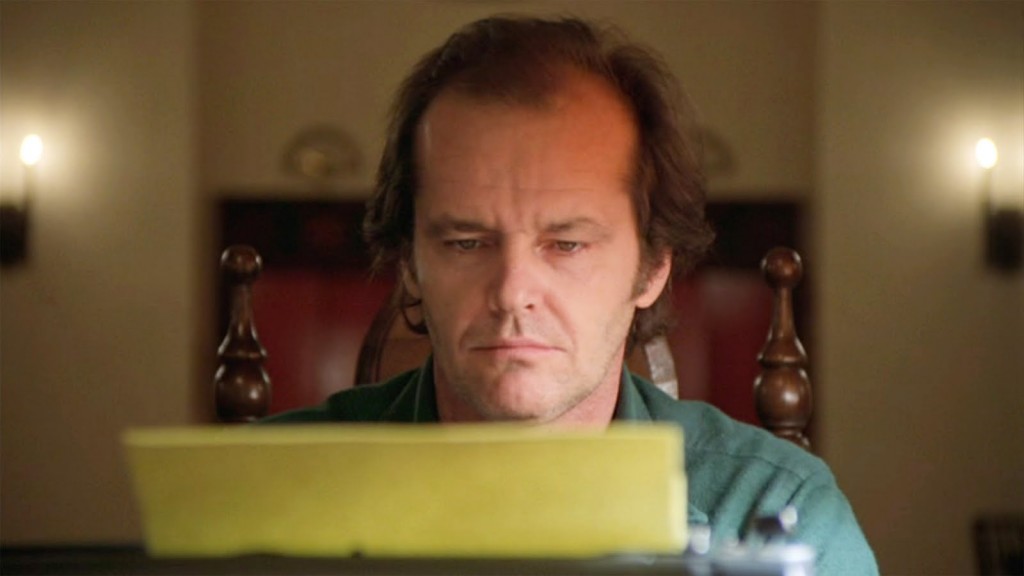

When Stanley Kubrick made The Shining (1980), he excised at least two scenes from the film before most people could see them. In one, Jack Torrance finds a magical scrapbook that explains some of the atrocities of the hotel. Another is a hospital scene where we see Wendy recuperating from the ordeal of her husband’s death (and murderousness), as well as her run-ins with ghosts.

The hotel manager, who we haven’t seen since he interviewed Jack for the job of hotel caretaker, now appears to console Wendy. He lets her know that her fears of the supernatural forces in the hotel were unjustified and that the authorities found no evidence of them. He also hands her a bouquet of bright red flowers. As he leaves the hospital wing where she is stationed, he sees Danny Torrance, Jack and Wendy’s son, and hands him a small ball. It is the same ball rolled to Danny by an unseen force from the open door of Room 237. We are meant to understand that the hotel’s devilish spirits live on—and that maybe they even live on within Danny and his mother.

From what I understand the hospital scene made it into the first showings of the film in LA and New York, but shortly after, Kubrick ordered his assistants to go into these theaters, splice the hospital scene out, and destroy the clips. All we have left are the screenplay and a few photographs, and the two scenes that bookend this empty space: Jack’s death in the frozen maze and the wall of photographs in the ballroom that place Jack at the hotel in 1921.

The Shining’s ending often confounds. Perhaps the deleted hospital scene would have given us more answers. In the pictures of the scene, Wendy’s hospital room looks plain, no frills at all. Her stare looks plain, too, and deathly blank, almost otherworldly as she attempts to find her way back to real life, after existing in the portal of the Overlook Hotel.

A hospital room is like a hotel room. Both are transitory, liminal spaces. You aren’t meant to stay in either and yet they are designed to make you feel “at home.” They provide all of the domestic trappings: a blanket, a pillow, a TV, a water cup. But these things are not necessarily objects that you would have chosen. They have no meaning to you. You are meant to not soil the sheets too much. For those same white sheets have to be bleached again and again for the next passenger on a trip to their own very specific hell.

*

Lately, I’ve heard people that say that horror is having a “moment.” I certainly hope that’s true. In the last few years, I have been a superfan of horror gods like Jordan Peele, Ari Aster, Carmen Maria Machado, Victor LaValle, and Ottessa Moshfegh. I cannot wait to read McSweeney’s new horror issue, edited by the amazing Brian Evenson. I hope to see more horror everywhere. I hope that the future of art will be drenched in red.

But as we live in such a hateful, violent world barreling toward its own destruction, what else has the capacity to speak to us but horror?

Horror has always been a sort of friend to me. I grew up in the 80s, which is known as a golden age of the genre. I remember first learning about the power of horror at my local bookstore, seeing a VHS cover of the movie Carrie placed next to some paperbacks. (Like The Shining, Carrie is also based on a Stephen King book.) I couldn’t have been more than five or six, and the cover terrified me. It portrayed that apex scene, when Carrie’s school bullies dump blood on her at the school dance, just as she’s anointed prom queen. In a split second she goes from glory to humiliation, her pale pink dress drenched in red.

Her vengeful eyes seemed to look down on me with disgust. I felt somehow like her sadness and fear were all my fault. Maybe that was how I was supposed to feel. After all, I was witnessing her pain, so wasn’t I complicit in it? And yet, looking up at her on high, like a bloody goddess, I felt a kinship. Just like Carrie, I was often bullied as a child for being strange. I felt a sisterhood in the look in her eyes, too. I couldn’t place it then, but 40 years later—and millions of hours spent steeped in her genre—maybe now I can begin to.

There is a feeling to this moment in time that seems particularly bleak. Maybe every era feels this way. Maybe it’s the lens of my middle age and my own preoccupations with nihilism that make it seem so. But as we live in such a hateful, violent world barreling toward its own destruction, what else has the capacity to speak to us but horror? As the climate crisis, war, poverty, book banning, and mass shootings are in the daily news alongside the latest celebrity breakups, the very genre of horror isn’t a fantasy anymore. We can imagine a world that is as unforgiving as the cold monster running at us with an ax because that’s how the world feels now.

Or maybe that’s how it’s always felt, and now we are waking up to that. We are all in the haunted hotel. Now all we can do is save ourselves by climbing out a tiny window and rolling down a snowy hill.

Or maybe caring for each other is the only way to heal. I still believe in that. Maybe all we are is a witness to our joy and pain. And maybe a good horror story—a space where everything completely terrible is simply acknowledged—is a human embrace after all.

Working on The Shining, I certainly felt that way. Everything felt so awful when I started writing it one day in a frenetic rush. I had even turned away from poetry itself. And yet the ekphrastic dream of my good friends at the Overlook Hotel, a space in my imagination for 20 years or more—they beckoned me. Or no, they welcomed me. They embraced me as I entered their space. They witnessed everything I was and forgave me anyway. They gave me poetry back to myself.

Maybe horror itself is a space to heal. Where we can exist in the excised hospital room of our dreams. Maybe if we turn to the art that frightens us still, we can make it all make sense.

*

I’ve always loved Sylvia Plath’s poem “Tulips.” It’s a terrifying poem, and one that gives its own horrible answers. The persona is in a hospital room that somehow presents itself as a healing space, where all of the past—with its ferocious, passionate hurts—can be forgotten.

Instead, the persona is haunted by tulips given to them as a gift. Their redness is an omen for all that is outside of the room that they cannot get to. The tulips are “too red.” They are a “dozen red lead sinkers” who “eat my oxygen.” They are a “loud noise” that cannot be stopped, for they remind the persona that life outside still goes on.

When I look at the images from the deleted hospital scene of The Shining, I cannot stop thinking of Plath’s poem. Plath’s persona feels like Wendy. They are both subject to who enters, to who brings them the red flowers they didn’t ask for. To who heals them, not on their own terms but on terms that represent a larger system and structure within which they are merely pawns.

In the end of Plath’s poem, the persona feels the beat of their heart again. They have for a moment forgotten the low hum of pre-death and instead enter a space where seawater can come in and bring back mementoes from a “country” as “far away as health.”

In the end of “Tulips,” “the bowl of red blooms out of sheer love of me.”

I hope so much that Wendy felt that way. That the bouquet of red flowers she was given bloomed with love. It’s hard to believe she ever came back from what happened to her. But I do hope that I am wrong. I hope someone eventually came along and loved her. Loved her with blooming, sheer love.

In the end of Mayer’s “The Way to Keep Going in Antarctica,” she writes: “If I suffered what else could I do.”

It’s true. What else can we do.

__________________________________

Dorothea Lasky’s poetry collection, The Shining, is available from Wave Books.