If anyone has ever told you Dune is a “tough read,” it would be interesting to see if that same person was able to read an eight‑hundred‑page Stephen King or Harry Potter novel. Although there are dozens and dozens of characters, and various layers of politics, religion, philosophy, and science fiction projections, if you’re able to keep track of more than five seasons of whatever TV show is hot right now, the story of the first Dune novel is not that tough to follow. The actual cause and effect of the novel isn’t subtle, even if Paul’s clairvoyance is spotty. As longtime sci‑fi journalist and Dune expert Paul M. Sammon noted in 2021, “a handy way to look at [Dune] is to think of Game of Thrones set on a desert planet. And instead of dragons think of giant sandworms, and instead of a battle for who will sit on the Iron Throne . . . think of a struggle of a young untested prince, who is unwitting and unwilling, at first, who winds up becoming, essentially, a religious messiah.” Not only is this analogy useful in tearing down funny biases a newcomer might have against Dune, but it also underscores the way in which decades‑old talking points have a pervasive habit of sticking around, even if those talking points no longer apply to the culture at large.

Haters like to say Dune is long and boring because people used to say Dune is long and boring. But that was decades before mainstream culture became obsessed with science fiction and fantasy. Readers and moviegoers in the twenty‑first century are probably more primed to enjoy and “get” Dune for its plot alone than perhaps any other generation before. In 1965, mainstream culture wasn’t inundated with complicated fantasy narratives. (Sure, The Lord of the Rings was published in 1954 and 1955, and The Hobbit in 1937, but it’s not like your grandma knew who Saruman was back then.)

But today, thanks to the bedrock of Tolkien, Doctor Who, Star Trek, Star Wars, anime, Marvel movies, and Game of Thrones, the average person — a phrase here that means “a person who has never gone to a comic‑con of any kind and likely never will”— is more willing and able to follow intricate feudal fantasy plots than they were in the 1960s. (Obviously, those of us who go to comic‑cons have loved Dune forever. That’s not the point. A sci‑fi or fantasy thing is mainstream only when it’s popular both inside and outside of “geek” circles.) In other words, the next time you need a reason to say Dune was ahead of its time, you can just say it invented Game of Thrones before Game of Thrones, complete with the tedious descriptions of food.

The first Dune novel — eventually published as a hardcover book in August 1965 — is a dense tome with a simple plot made complicated on purpose. It goes like this: In the distant future, Duke Leto Atreides is ordered by his emperor to pack up and leave the super‑cozy oceanic planet Caladan and move to a desert‑planet hellhole, Arrakis, nicknamed “Dune.” The stated job is to take over the production of spice, a freakishly valuable natural resource that can only be mined on Arrakis, which is very tricky because the planet is an inhospitable wasteland crawling with giant sandworms. If there’s one thing a non‑Dune person knows about Dune, it’s those sandworms, perhaps the most iconic space beasts in all fantastic literature. In 1978, for a special audio version of Dune, Herbert made his artistic intents with the sandworms clear: “The concept behind the sandworms of Dune has attracted swarms of questions and speculation. The answer is that they are ‘the mindless monster[s] from the depths.’ At the same time, they are the guardians of ‘the priceless treasure.’ They are both the source of treasure [the spice] and the source of infinite danger. What is that, except the embodiment of all the unknowns which confront questing life, questing awareness.”

Herbert’s interest in Middle Eastern history was linked to his research about deserts and the overall history of world religion. And so this naturally led to a study of Arabic. Throughout Dune, Herbert transmogrified various Arabic words to describe the nomenclature of Arrakis. Karin Christina Ryding, a professor of Arabic at Georgetown University, points out that the Fremen word for the sandworms —shai hulud—is likely derived from Arabic. “If taken as written by Herbert, the term shai hulud could translate as ‘immortal thing’ or ‘eternal thing’ (shay’ khulūd),” she writes. But Ryding also adds “fanciful speculation” that another reading could be interpreted as “old grandfather whale.” In the 2021 movie, Paul says to himself, “I recognize your footsteps, old man,” which references the fact that Paul has Gurney’s walking pattern memorized, but also reminds us that the Fremen like to call the sandworm the “old man of the desert,” which, again, is backed up by the Arabic references.

Books have the ability to travel into the future in a way that no other written medium does.

But old whale-like sandworms and scheming Harkonnens (All these people are Homo sapiens, by the way. There are no space aliens in the Dune galaxy. There are shapeshifters called Face Dancers, pseudo‑clones called gholas, mutated Guild navigators who look like fish in tanks, and, of course, giant alien sandworms, which are technically animals. But no actual aliens.) be damned, the plot of the book begins as Leto moves his whole family and staff—including his son, Paul, and his bonded concubine Jessica—to the planet Arrakis. As we know, Jessica has trained her son, Paul, in the ways of the Bene Gesserit (including the Voice). For thousands of years, the Bene Gesserit have been trying to breed a super‑being called the Kwisatz Haderach, and they believe Paul could be it. Meanwhile, the Fremen, the desert‑dwelling people of Arrakis, also think Paul could be their messiah and lead them to freedom. Spoiler alert: Everyone is (kind of) right. With the help of the spice, and later, the Water of Life (sandworm bile!), Paul can see the future (inconsistently), which allows him to become the (convenient) messiah for the Fremen, if not quite the Kwisatz Haderach. After his father is killed in an almost instant Harkonnen invasion, Paul and his mother, Jessica — who is pregnant with Paul’s baby sister, Alia — flee into the desert of Dune, where they meet up with the Fremen.

After a ritual knife fight and some spicy coffee, Jessica becomes the reverend mother for the Fremen, and Paul becomes the Fremen’s messiah and learns to ride giant sandworms. Then, with the help of his Fremen lover (not wife!), Chani, and his baby sister, Alia — who is born with the memories of all her ancestors — Paul, the remaining members of House Atreides, and the Fremen ride those sandworms real hard, crush the Harkonnen forces, and conquer the galaxy. The first book ends with Paul’s becoming the emperor as the underdogs of the universe become the top dogs.

Critically, none of this could have happened if Dune had remained a half‑completed serial in a science fiction magazine with a circulation of one hundred thousand copies. Sure, one hundred thousand copies of a magazine seems like a lot, but magazines don’t have the same kind of shelf-life as books. Literally. Today, short stories in magazines might be available digitally after the issue is no longer on sale, but that technology obviously didn’t exist in the 1960s. A series of linked short stories in a niche‑interest magazine couldn’t possibly hope to reach a massive audience. Books have the ability to travel into the future in a way that no other written medium does.

__________________________

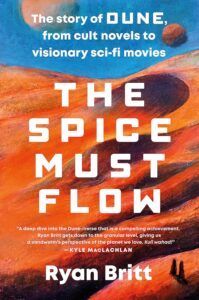

Excerpted from The Spice Must Flow by Ryan Britt. Used with permission of the publisher, Plume. Copyright © 2023 Ryan Britt