Why turtles? Alexxia Bell, Turtle Rescue League’s president and co-founder Natasha have, in their years together, rescued other creatures, from squirrels to salamanders (including a skunk they found on their way to pick up an injured turtle; once inside their little car, and with an hour left to travel, the animal, in extremis, sprayed its musk). What makes turtles so special?

I’d been thinking about this for some time. Turtles do have a big fan base. In some cases, this is literal: At New England Aquarium, by far the most popular of its tens of thousands of animals is Myrtle, a ninety-year-old, 550-pound green sea turtle who has lived there since 1970. She has her own Facebook page with more than seven thousand followers. Turtles star as heroes of stories, comics, and movies, from the Tortoise in Aesop’s 2,600-year- old fable, to the Teenage Mutant Ninjas, to wise Crush and little Squirt in Finding Nemo. Turtles are popular subjects of artwork, collectibles, and toys; there is even a Turtle Splash breakfast cereal, which comes with a free baby sea turtle adoption kit.

Almost everyone has seen a turtle, and most people my age once lived with one. Every dime store in the United States carried inch-long baby red-eared sliders in the 1950s, ’60s, and midway through the ’70s—along with tiny round terrariums, each with a spiral ramp topped by a plastic palm tree. Unfortunately this was a completely inappropriate habitat for animals who should command a home range measured in square kilometers and live for fifty years. And their food was wrong, too: Most of us were sold ant eggs to feed them, when baby sliders really need a variety of insect and invertebrate prey, as well as vegetables and other plants, to eat.

Unlike most reptiles, turtles don’t frighten us.

But it was no wonder these doomed infant turtles were such popular pets. A baby turtle fits perfectly into a child’s hand. (And also elsewhere—which was why some kids were getting salmonella, and the sale of turtles less than four inches long, the width of a child’s open mouth, was banned in 1975.) Unlike most reptiles, turtles don’t frighten us; they seldom bite, and they don’t slither or scurry, but move slowly enough that we can watch them for a while as they charmingly carry their “house” on their back. When I was growing up in Virginia and New York and New Jersey, every kid had one—often several in succession, because most quickly died. (My parents rushed to replace them before I found out.) All of mine were named Miz Yellow Eyes.

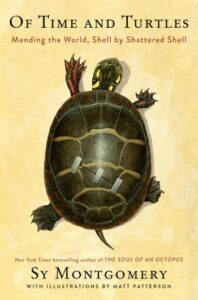

Like me, my friend Matt Patterson, a wildlife artist, loved turtles from an early age. “I’ve been a turtle nerd my whole life,” he will tell you proudly. His earliest memory is of heading out in a rowboat with his father, a biology teacher, to look for turtles when he was three. Later, he and his dad built fenced outdoor enclosures for turtles they would find and bring home. “We didn’t know back then we were doing anything wrong,” he explains, now fully aware that taking native animals from the wild is illegal. “I just loved them and wanted them with me so I could watch them.”

He’s never lost that boyish Huck Finn attitude, nor his love of outdoor adventure. He’s a bit feral. It doesn’t seem like a house or an office could hold him for long—and it never has. After graduating from art school, he worked a scant two and a half years as a product design illustrator in different offices, “always looking out the window, dreaming of somewhere else.” One of the offices where he worked was by a river, so he’d bring his kayak so he could fish and look for turtles on his lunch break. But as soon as he could, he quit the office to work for himself, concentrating exclusively on wildlife art—creating images so vividly realistic that when I saw a photo of one of his turtle paintings that happened to have his hand in the frame, I thought the hand was fake and the turtle was alive.

Matt’s always ready to head out in his flip-flops to wade into a river or stream or swamp. Any place that’s good for turtles is good for Matt Patterson, and he will go anywhere, and do anything, to observe, to paint, or to help them.

He’s combined his turtle expertise with college wrestling skills to wrangle monster snappers into his canoe for close-up views. He’s traveled to the Spiny Desert of Madagascar with the conservation group Turtle Survival Alliance to meet critically endangered radiated tortoises in the wild. He haunts herpetology conferences and trade shows where turtles are prominently featured—where, to his wife’s dismay, a common question strangers ask each other is “How many herps do you have?” (“Sounds like the symptoms of a horrible disease!” she remarked.)

He’s been with his three-toed box turtle, Polly, longer than he’s known his spouse. He’s been married to Erin, a speech and language pathologist, for a decade. He’s been with Polly for twenty-four years. The largest of his four pet turtles is Eddie, an African spur-thigh tortoise who he thought at first was male. She’s only twenty pounds now, but she could grow to one hundred pounds and live up to 150 years. (He plans to build Eddie her own barn, and has provided for her in his will.)

What inspires such allegiance? Once Matt wrote out his feelings in an email to his mom. Though she tolerated with grace a home overrun with animals of all kinds—escaped snakes, a pet alligator, and a collection of turtles that once spanned fourteen species—to Matt’s continuing dismay, her appreciation for turtles falls short of his own.

“Did you know,” Matt wrote to her with the zeal of a disciple, “the first animals to orbit the moon were tortoises?” (They were a pair of unnamed steppe tortoises aboard the Soviet Zond 5 space probe in September 1968.) “Did you know some species live over two hundred years?

“Turtles are as old as the first dinosaurs, older than the first crocodiles, and have been around for over 250 million years. Unlike us,” he explained, “turtles are extremely important to the planet’s biodiversity! Some turtles, like snapping turtles, are the vultures of the ponds, lakes, and rivers, eating dead and decaying animals and plants. Gopher tortoises are considered a keystone species,” he continued, noting that over 360 other species depend on this one kind of turtle, and their burrows, to survive. Other turtle species are equally essential to their ecosystems: Hawksbill sea turtles protect coral reefs by eating sponges, and other sea turtles eat jellyfish, which keeps them from overpopulating….

Matt pressed on, filling a full page of single-spaced type. “This is why I love turtles,” he concluded, “and this is why my work is dedicated to helping protect them.”

Turtles’ familiarity is a doorway to appreciating their strangeness.

Many of these same reasons inspire Alexxia’s, Natasha’s, and my own love for turtles, too. Turtles’ familiarity is a doorway to appreciating their strangeness. Turtles are unlikely, surprising animals. The more than 350 species of turtles, gracing six continents, display breathtaking talents. One, of course, is their longevity: A turtle who recently died at age 288 was alive when George Washington was born, when homes were lit by candles, medicine largely consisted of enemas and bloodletting, and mental illness was treated with powder made from the hooves of moose. Another turtle had a baby at age 140. Some can sense a lake or pond a mile away; others migrate across entire oceans to find the very beach where they hatched decades earlier. Some breathe through their butts; some pee through their mouths. Some stay active under ice-covered waters; others climb fences and trees. Some are red, some are yellow, and some change color dramatically once a year. There are turtles with soft shells, turtles with necks longer than their bodies, turtles with heads so big they can’t retract them, turtles whose shells glow in the dark. Some turtles could even help us cure cancer. Asian mayapples, the source of etoposide, used to treat lung and testicular cancer, have been harvested almost to extinction. American may- apples provide an effective substitute, though the plant’s seeds are extremely difficult to propagate—unless the seeds are ingested and excreted by box turtles.

Alexxia deeply respects turtles and their powers. But she also finds them hilarious. “They look so goofy,” says Alexxia. “Let’s design an animal that will persist for almost three hundred million years. You wouldn’t design a turtle, with those pretty shells. You’d design something with big jaws, a huge brain—not something that falls upside down and can’t get up.”

Natasha concedes that “a lot of people might think it’s completely ridiculous that we spend this amount of time and money and energy on turtles.” True, most people like turtles, and many love them. “But how many times have I been standing at a booth at an event when someone asks, ‘What is the purpose of turtles?’”

Alexxia gets frustrated when people ask what turtles have done for us. “They don’t have to do anything for us!” she says, her temper flashing. “What are we doing for them?”

“Why turtles? Why art?” asks Natasha. “Why have children?

Why anything?”

“They were here first!” Alexxia insists. “They are what life is, what life does—and they are worth saving.”

“Here’s an animal that walked with the dinosaurs,” Natasha explains. “The earth warmed and cooled, warmed and cooled, and they are still here. But we are messing them up. Why shouldn’t we be driven by a desire to set things right for them?”

For Alexxia too, it’s as simple as this: “Turtles need more help than any other wildlife,” she says. She’s right: Turtles are the most imperiled major group of animals on earth. Like other wild animals, turtle populations shrink when houses, roads, and stores displace their homes. They suffer from pollution, climate change, and invasive species. Cars run them over. Dogs, raccoons, skunks, and otters chew them up. And on top of all this, there is a murderous, monstrous illegal trade in turtles—for their meat, for their eggs, for their shells, and for pets. “Helping any animal is a good thing,” Alexxia had told the group who’d gathered for the turtle summit last year. “Saving a chipmunk is a good thing. But if you save a turtle, particularly a female turtle, she may be able to lay eggs for another hundred years. With each turtle you save,” she said, “you are saving generations.”

__________________________

Excerpted from Of Time and Turtles: Mending the World, Shell by Shattered Shell. Copyright © 2023 by Sy Montgomery with illustrations by Matt Patterson. Reproduced by permission of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved.