“I happen to think that a work of art must not be suppressed and that an artefact of calculated corruption should be prosecuted.“

–George Weidenfeld

*

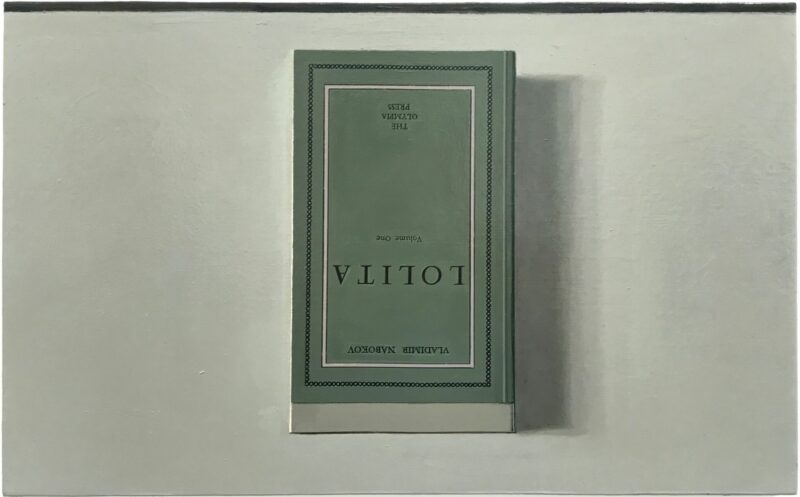

Lolita was originally published as a limited edition in France in September 1955. The book was released by Maurice Girodias of Olympia Press, a company known for specializing in pornography, but which had also built a reputation for publishing challenging literary titles. The first print run had been 5,000 copies and the book received little attention.

Over the next few months, a handful of copies of Lolita were smuggled into England. A single copy made its way into the hands of Graham Greene, who reviewed it favorably in the Sunday Times. This was followed soon after by a scathing article in the Sunday Express, which denounced the book as “sheer unrestrained pornography.” Shortly after, the British Home Office ordered that all copies entering the country should be seized.

When he first read Lolita, George Weidenfeld knew immediately he wanted to publish it. His partner, Nigel Nicolson, was not so sure. Nor were Nigel’s parents. His father Harold Nicolson “hated” the book and said it would be “universally condemned,” while his mother Vita Sackville-West “saw no literary merit in it at all.” As for Nigel himself, he told George that he was not convinced they should proceed with publication.

George was unrelenting. He took legal advice, however, and learned that publication in England would be extremely hazardous. Under the current law, they would likely lose the case, which would result in huge losses. Any copies that had been printed would have to be pulped, not to mention the enormous editorial, marketing, publicity and legal expenses incurred up to that point. Such an outcome would be calamitous for Weidenfeld & Nicolson, placing its future in serious jeopardy.

As luck would have it, the lawyers said, the Labour politician Roy Jenkins was right then guiding a new obscenity bill through Parliament. Under this new law, if the government blocked publication and the case went to court, then the publisher would be able to argue the literary merits of the book by calling authors, academics and reviewers to testify. If this bill was enacted, then just maybe, George might have a chance. The effort would still pose an enormous risk but, for the publisher, it might be worth it.

In the decades leading up to the proposed publication of Lolita, governments had frequently cited “obscenity” as the reason for preventing controversial books being published. In the United States, the Federal Anti-Obscenity Act of 1873 had been used to ban Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, John Cleland’s Fanny Hill, Boccaccio’s The Decameron and Voltaire’s Candide. In Britain, the legal test for obscenity derived from a 1868 case known as Regina v Hicklin, in which a judge ruled that obscene material tended “to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influence.”

In the decades leading up to the proposed publication of Lolita, governments had frequently cited “obscenity” as the reason for preventing controversial books being published.

In 1928 the British government had relied on the Hicklin case to ban Marguerite Radclyffe Hall’s lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness. Opposition to the book was whipped up by the media, particularly the Sunday Express whose editor wrote, “I would rather give a healthy boy or a healthy girl a phial of prussic acid than this novel.” That same year, D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover was also deemed to violate the obscenity laws and was commercially published in only an expurgated version. Six years later, the publisher Boriswood was prosecuted for obscene libel and severely fined for releasing Boy, a sexually explicit novel by James Hanley.

Over the summer of 1958, with the lawyers saying that the new bill had a good chance of passing through Parliament, and with Nigel Nicolson’s tenuous but nervous agreement, George reached out to the author, Vladimir Nabokov, in New York and asked for permission to publish Lolita in the United Kingdom and across the Commonwealth. By the end of November, they had reached an agreement on the general terms and Nabokov wrote to George saying “an English edition of Lolita is nearing signature.”

In his reply to the author in New York, George said, “May I take this opportunity of telling you how inspired and moved my colleagues and I feel by the book and how determined we are to see that it launches with dignity and success in this country.” Publication of Lolita in Great Britain seemed a little closer, but then, by the year’s end, George’s plans started to unravel.

When word began circulating in the press that Weidenfeld & Nicolson intended to release Lolita, Nigel’s political colleagues pressed him to change course. At one point the Conservative chief whip Ted Heath (and later prime minister) begged him to cancel publication. Nigel asked him if he had read the book. Heath said he had. “Did you think it obscene?” Nigel asked. “As a matter of fact I thought it very boring,” Heath replied. “If it is boring it cannot be obscene,” Nigel said, which he later admitted was not a very good argument.

A few days later, the Attorney-General, Reginald Manningham-Buller (called “Bullying Manner” behind his back), stopped Nigel in a dark corridor in the bowels of the House of Commons. “If you publish Lolita you will be in the dock,” he said, jabbing a finger at him. “Even after the Obscenity Bill has been passed?” asked Nigel. “That won’t make any difference,” responded the country’s top lawyer. ‘The book is thoroughly obscene. I’ve given you a clear warning.”

On 16 December 1958, a week before Christmas Eve, Roy Jenkins’ new Obscenity Bill was debated in the House of Commons. Midway through the proceedings, Nigel stood up to speak. First, he acknowledged that he had an interest in the matter as a director of the firm Weidenfeld & Nicolson, which was planning to publish Lolita. Then he moved on to the substance of his speech. “The question could be asked,” he declared, “Is an obscene work of art a contradiction in terms? I would answer the question by saying, no, it is not. It is quite possible for a work of art to be obscene.” He then went on to say that the book had already been published in America, where over 250,000 copies had been sold.

Lolita had also been published in France and Italy. “The question arose whether it should be published in England. That was the question which my colleagues and I had to answer,” he continued.

Lolita deals with a perversion. It describes the love of a middle-aged man for a girl of twelve. If this perversion had been depicted in such a way as to suggest to any reader of middle age or, for that matter, any little girl—could she understand it—that the practices were pleasant and could lead to happiness, I should have had no hesitation in advising my colleagues that we ought not to publish this book. But, in fact, Lolita has a built-in condemnation of what it describes. It leads to utter misery, suicide, prison, murder and great unhappiness, both to the man and to the little girl whom he seduces.

At this point, Emrys Hughes, a Welsh Labour MP, rebel and general troublemaker, tried to interrupt, but Nigel brushed him aside and moved on to his conclusion. “I asked myself whether the loss to literature in this country through the non-publication of Lolita was greater than the risk which one ran of offending certain people by its publication.” Pausing to take a breath, he then said, “In the end, I came to the conclusion that it was probably right to publish this book.” Nigel had for the first time publicly declared his support for the publication of Lolita.

George must have been pleased. Over Christmas, he reached out to his growing network of authors, some of whom he published, and some not. He asked them to add their names to a letter in support of Lolita. Just before heading off for a trip to Holland, then France, he sent the letter to the editor of The Times—the British newspaper of record. He had succeeded in gathering the names of some of the most well-known intellectuals of the time, including the authors Iris Murdoch, Stephen Spender and Peter Quennell, along with the philosopher Isaiah Berlin and the publisher Allen Lane. Somehow, he also managed to persuade the editor of the Times Literary Supplement, Alan Pryce-Jones, and the totemic critic S. Pritchett to add their names as well.

The letter was published on Friday 23 January 1959. “We are disturbed by the suggestion that it may yet prove impossible to have an English edition of Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita,” it began. “Our opinions of the merit of the work differ widely, but we think it would be deplorable if a book of considerable literary interest which has been favorably received by distinguished critics and widely praised in serious and respectable periodicals were to be denied an appearance in this country.” George had done well.

Over the spring, while the furore continued, and they waited in hope that the House of Commons would approve the new Obscenity Bill, George and his team attempted to identify a printer brave enough to take on the government’s censors.

But any sense of progress was halted when, two days later, another letter was published in The Times. This time from Douglas Woodruff, editor of the Catholic paper the Tablet, in response to the letter signed by Iris Murdoch and her literary friends. He argued that writers and artists had a responsibility to “bear the claims of public decency in mind in a way that the author of Lolita chose not to.” Then Woodruff added his most cutting point: “If literary merit, such as will always be argued for, is to carry complete exemption, that will mean the claims of public decency are to count for nothing at all against the claims of liberty and art.”

That same day, a slightly rattled George Weidenfeld arrived back in London and immediately wrote to his author in New York. He started the note with “Dear Mr Nabokov,” for they had not met and still addressed each other formally. George now reported that the letter to The Times from Iris Murdoch and her other signatories was “obviously very helpful” but that the rejoinder by Douglas Woodruff was “the first seriously argued thrust of counter attack.” The key to a successful publication, he continued, would be the passage of the new Obscenity Bill through Parliament, which he hoped would occur sometime that autumn. He then said he was looking forward to meeting Nabokov in person, and signed the letter.

Over the spring, while the furore continued, and they waited in hope that the House of Commons would approve the new Obscenity Bill, George and his team attempted to identify a printer brave enough to take on the government’s censors. Typically, a publisher worked with a limited number of printers. This was not just a matter of economics—the higher the volume, the lower the cost—but also of art.

Each publisher had their own particular preferences when it came to the making of a book. What font might be used: Helvetica, Penumbra or perhaps Futura. Which paper stock: light, heavy, clean-edged, rough-edged? The type of board used to bind the book. The kerning (the space between the characters) and the leading (the space between the lines). Whether a ribbon was to be added to bookmark a page. Or perhaps attractive endpapers pasted onto the inside of the front and back covers.

Each of these required numerous choices and, over time, the publisher and printer formed a creative partnership. It was also a matter of trust. The printer was unable to read every book that ran through their machines, thousands a year, so they relied on the publisher for guidance in case there were potential problems.

The task of finding a printer was given to Nicholas Thompson, editorial director of Weidenfeld & Nicolson. He approached one printer and then another. Each turned him down. Some of the responses were defensive and short. Others, embarrassed and awkward. One of those who declined was Richard Clay, managing director of Clay and Company, the largest printer in England.

“From a purely personal point of view, the inconvenience which would be caused in the event of there being a case brought by the DPP [Director of Public Prosecutions] would be something which I could not risk,” wrote Clay, continuing “quite apart from the fact that, should the prosecution be successful (my impression is that there is a bit of a witch-hunt going on in some of the higher legal circles) I should find it extremely inconvenient to be incarcerated, even though it would be at the taxpayer’s expense!”

Finally, on 8 May, George had something positive to report to the Nabokovs. “I am at last able to give you some really constructive news about Lolita,” he wrote. “Having had over thirty refusals from printers, I am happy to tell you that Shenval Press, whose head James Shand is a good and reliable friend, has now agreed to print Lolita as soon as the new Obscenity Bill becomes law.” A month later, on 15 June, he wrote again, informing the author that the bill had passed through the House of Lords with an amendment, though, George reassured him, the amendment ‘does not affect Lolita in any way.”

As a sign of his confidence, George had now sent the book to the printer and begged them to be “extremely circumspect and discreet,” lest the newspapers got hold of the story that the book was being printed before the bill was passed. In another letter he told Nabokov that it would be disastrous if there was more publicity during the next fortnight, which might give their enemies a chance to filibuster the bill beyond the present parliamentary session. However, George concluded, “we have gone a long step further towards L Day.”

Frustratingly, the printing was held up again by a strike that broke out over the summer. When it ended in the first week of August, the book finally went to press. Two weeks later, a handful of sample copies arrived at the office at 7 Cork Street. George and his colleagues gathered around to look at the newly minted book.

It looked stunning. The dust jacket was an attractive but modest apricot color. On the front was printed the title “Lolita” in large capital letters, beneath which ran a white line and, under that, the author’s name. Nothing more. The back cover had a large photograph of Nabokov looking straight at the camera, daring the reader to pick up the book. Beneath his picture ran a short biography of the author, ending with his passion for collecting butterflies. The spine had the book’s title, the author’s name and then, at the bottom, much to George’s pride, the publisher’s logo: “Weidenfeld & Nicolson.” They were now ready to put the second phase of the plan into action.

By the end of October, they now had a decision to make. Two months had passed and still there was no response from the government. Around twenty-thousand copies of Lolita had been sent to bookshops around the country and these booksellers were anxiously awaiting the go-ahead to put the books on their shelves. Vladimir and Véra Nabokov had flown in to London for the publicity tour and were staying at Brown’s Hotel in Mayfair. Should they publish?

So it was that on 1 November 1959, George met with Nabokov and his wife at the White Tower restaurant in Bloomsbury. Also present were Nigel Nicolson, the critic V. S. Pritchett and the Labour politician Roy Jenkins. Nobody argued for delay, they were too committed now. It was full speed ahead.

Four days later, on 5 November 1959, Guy Fawkes Day, more than 200 people gathered at the Ritz Hotel in London, waiting for the news. The crowd consisted of prominent actors, musicians and authors, as well as dozens of eminent journalists, editors and lawyers. At the centre of the proceedings was George Weidenfeld. Never still, moving from one small group to another. Making introductions. Catching up on the gossip. Suggesting that whoever he was speaking with might consider writing a book.

Around him, the room was humming with anticipation. They were waiting to hear whether the government would finally allow Lolita to be published. The press was already calling it one of the most important books of the year. If George was able to make Lolita a success, it could transform the fortunes of his fledgling publishing house.

Then, around 10 p.m., one of the hotel’s staff members called George to the phone. There in an alcove he picked up the receiver and asked who he was speaking to. The man on the other end of the line would only say he worked in the Home Office. George was impatient to hear the news. After some pleasantries were exchanged, the civil servant eventually got to the point. “This is highly irregular,” said the man, “but I am a great supporter of your cause.” A few moments passed, then he continued. “You can go ahead. The DPP has decided not to prosecute.”

George walked back into the ballroom and announced the news. The crowd cheered loudly. Champagne glasses were clinked, hands were shaken, backs were slapped. Vladimir Nabokov stood to one side smiling. His wife Véra rubbed away a tear with a handkerchief.

f George was able to make Lolita a success, it could transform the fortunes of his fledgling publishing house.

George then excused himself and placed two more calls. First to the office, telling them to relay the news to the bookshops. Lolita could immediately be sold. A second call was made to James Shand, the printer, thanking him for his loyalty and urging him to run off as many copies as possible.

The publication of Lolita attracted enormous coverage in the press. The Western Mail said it was “among the most interesting books to appear in the last decade.” Elizabeth Harvey in the Birmingham Post called it ‘brilliant writing’ and ‘a work of art’. The syndicated journalist Harry Thompson described it as ‘the most controversial novel of the century’, while the columnist David Holloway noted in the Daily News that ‘No book in my lifetime has caused more pre-publication fuss than Lolita.’

Not all the critics were so effusive. On 12 November, a week after Lolita’s publication day, The Times ran an anonymous review under the modest headline New fiction. They said that Lolita “is not a book to be proud of,” adding “its construction is much looser than its morals and it is written in a style which sets the teeth on edge.” After admitting that Nabokov was writing in the person of the main character, Humbert Humbert, The Times then added, “Nobody is likely to be corrupted by this book, but very few readers are going to be much entertained by a study of mania which is neither objectively clinical nor emotionally engaging.” Given the book’s subsequent longevity, the reviewer was probably grateful they remained unnamed.

The first print run sold out immediately. As did the next and the next. This was so unusual that the New York Times ran a story under the headline Lolita’s a Sellout in Britain. Within two weeks, more than 80,000 copies were sold. Then 100,000. Then 200,000. The printer struggled to keep up with the orders not only from within Britain but in Australia and other Commonwealth countries.

Today, Lolita is considered a modern classic. Ranked as the fourth-best novel of the twentieth century by the Modern Library, thirteenth best by Time magazine, fifty-fourth by the Telegraph, and sixty-ninth by the Guardian. Lolita is also a cultural touchstone that is frequently referred to. In the song, “Don’t Stand So Close to Me,” Sting warbles “Just like the old man in that book by Nabokov.” Similarly, in the film Manhattan, Diane Keaton’s character Tracy says, “Somewhere Nabokov is smiling” when she discovers that Woody Allen’s character Isaac is dating a seventeen-year-old.

Is it possible to separate the morals of the fictional, albeit unreliable, narrator from the author who created them?

Meanwhile, the word “Lolita” has even entered the English language as a noun: “a precociously seductive girl,” according to Merriam-Webster. Opinion about the book, however, remains divided. While many argue that the main characters are compelling, the writing style brilliant, and the colorful descriptions of the American Midwest captivating, others vehemently disagree. They point out that Lolita was just twelve years old when she was kidnapped and raped multiple times by Humbert Humbert, and that the author does not sufficiently signpost this as a problem, making the book immoral.

This extreme divergence in viewpoint has created a cultural flashpoint around the book, raising a number of larger questions about literature and the responsibilities of a publisher: is it possible to separate the morals of the fictional, albeit unreliable, narrator from the author who created them? And if not, can a book be too morally repugnant to be published?

“It was a triumph for George,” Nigel Nicolson later wrote. “His nerve had held in face of much discouragement including my own.” As for the publisher himself, he was euphoric. “Lolita was a breakthrough in the liberalization of the British obscenity laws,” George later said.

The following year, Penguin Books used the same argument as had been deployed for Lolita—literary merit—to persuade a judge that they could publish an unexpurgated version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in Britain. It would take another decade for English courts to allow works that were considered obscene but without literary merit to be published, starting with Oz magazine in 1971.

______________________________

The Maverick: George Weidenfeld and the Golden Age of Publishing by Thomas Harding is available from Pegasus.