The idea of a comedy blockbuster used to be an ordinary event in Hollywood. Charlie Chaplin was, and likely still is, the biggest star ever produced by the movies. Laurel and Hardy, Jerry Lewis, Marilyn Monroe, Mel Brooks, and Eddie Murphy brought in massive crowds. From The Producers to Beverly Hills Cop to Meet the Parents, comedy was Hollywood’s bread and butter. And then, starting only a few years after the release of Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy—the topic of my new book, Kind of a Big Deal: How Anchorman Stayed Classy and Became the Most Beloved Comedy of the Twenty-First Century—the film-comedy production line sputtered to a halt.

In reality, there has not been a genuine comedy blockbuster since Bridesmaids, which came out 12 summers ago. Since then, Melissa McCarthy has starred in a string of successful vehicles, including The Heat and Spy, and Kevin Hart has had a handful of hits, including Ride Along and Central Intelligence, but the ground has grown increasingly sparse.

In the bad old days of—checks notes—a few years ago, each new movie starring women, whether it was Bridesmaids or Ghostbusters, was treated as a referendum on whether women were funny. (Verdict: they are.) Now, so few comedies are being made that each one is treated as a referendum on whether comedy can draw audiences to the movie theater. And the results have been disheartening. Anyone see No Hard Feelings, with Jennifer Lawrence as a woman hired to deflower the clueless college-bound scion of a wealthy family? Me neither. (The 800-pound exception is, of course, Barbie—more on that momentarily.)

So why is it that comedy has receded so thoroughly from the big screen? I’d point to three prime factors, each of which can be illustrated partially through the success of Anchorman and what came afterward.

First of all—and Barbie is less the counteracting of this trend than a stark representation of it—in contemporary Hollywood, IP is king. Practically every movie that makes it to the multiplex is offering a variation on a familiar story, be it the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Star Wars, Transformers, Mission: Impossible, or Jurassic Park. And even movies that feel a bit fresher are often working off the sturdy platform of an instantly recognizable figure, object, or product, whether it’s Mattel’s iconic children’s toy or the Air Jordan sneaker.

There are fewer and fewer movies that begin with a blank page, and audiences have grown accustomed to the familiar. Perhaps too familiar: this summer has witnessed faltering audience interest in sequels like Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny and Fast X. Studios’ cynical buckraking, with yet another Marvel multiverse film with hastily executed CGI, or another live-action remake of a beloved Disney animated film, has sapped moviegoers’ belief that they deserve better. And comedy, by not easily lending itself to ceaseless franchising and rebooting, has receded as a genre.

Second, Hollywood increasingly depends on international box office to drive profits. Movies have to play well overseas to justify the ballooning costs of feature filmmaking, and comedies, in large part because of their cultural specificity, perform poorly overseas. Studio bosses are increasingly reluctant to green-light $100 million comedies if they know that the possibility of a nine-figure international haul is remote.

In contemporary Hollywood, IP is king.

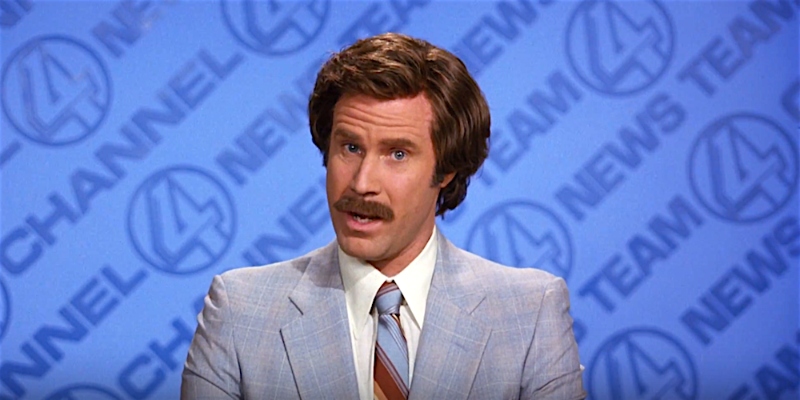

The increasing paucity of comedy blockbusters also leads to the third factor: the aging of bankable comedy stars. When we think of stars who can open a comedy, we are mostly thinking of the same performers from over a decade ago: Ben Stiller, Seth Rogen, Melissa McCarthy, and of course Will Ferrell. But Stiller and Ferrell are both in their mid-50s now, and even the jovial slacker stoner Rogen is 41 (and starring in an Apple series alongside his former Neighbors castmate Rose Byrne).

The decreasing number of slots for big-budget comedies also means that the next generation of comedy movie stars never developed. Instead, they navigated their way to television, a far more hospitable home for gifted performers: see Donald Glover, Phoebe Waller-Bridge, Rachel Bloom, Quinta Brunson, and Bill Hader.

Comedy has generally catered to youthful audiences (even when the stars themselves, like Leslie Nielsen of The Naked Gun, were silver-haired veterans). Stiller and Rogen are still wonderful performers but may feel less relevant to 14-year-olds, for whom they are their dads’ favorite comedians.

In retrospect, the era from 2000 to 2011—which included not only Anchorman but the McKay-Ferrell collaborations Talladega Nights and Step Brothers; Anchorman producer Judd Apatow’s The 40-Year-Old Virgin and Knocked Up; Stiller’s Meet the Parents and Zoolander; Mean Girls; Bridesmaids; and Wedding Crashers—may have been blockbuster comedy’s final golden era. Performers like Ferrell, Stiller, Vince Vaughn, Paul Rudd, Kristen Wiig, Rachel McAdams, and Owen Wilson were bankable comedy stars, grouped in an unceasing array of round-robin pairings. And studios were willing to invest money in comedy, and take risks on untested performers, writers, and directors.

In this, the production of Anchorman is instructive. This was not a pre-existing piece of IP. This was a string of jokes and asides deposited by two SNL veterans in what they called their “big messy bag of ideas,” and given the time and encouragement (particularly through the involvement of Apatow) to develop into a winning movie.

Comedy, by not easily lending itself to ceaseless franchising and rebooting, has receded as a genre.

The screenplay, written by then-Saturday Night Live star Ferrell with SNL head writer Adam McKay, began as a story about newscasters whose plane crashes, driving them to cannibalism. It then transformed into a story about Ferrell’s character, Ron Burgundy, taking on the Alarm Clock, a radical group with a vague ideological agenda, before eventually becoming the more familiar newsroom battle of the sexes.

Anchorman lingered in studio limbo for years before getting a green light because of concerns that Ferrell, by then a familiar face on SNL, might not be enough to open a movie. (In one instructive example, a production company rejected Anchorman, choosing to instead produce the David Spade vehicle Dickie Roberts: Former Child Star. Whoops!) It took the surprise success of Old School, directed by Todd Phillips and featuring Ferrell, to convince DreamWorks to make Anchorman. Old School has been rebranded in fans’ minds as a Will Ferrell movie, but Ferrell was actually third-billed on the 2003 film, after Luke Wilson and Vince Vaughn. Ferrell was like a minor-league phenom called up to the big leagues and granted the opportunity to star in his own film. With so few comedies being made now, where might the next Will Ferrell come from?

The comedies of Anchorman’s era were, in short, about people, which may at first appear to be a tautology—what else would the movies be about besides people?—but is increasingly rare in our current era of runaway IP. These comedies, hilarious and imperfect, are a reminder of a wilder, woollier, more humane era of moviemaking, telling stories meant to shock us into laughter, but also, possibly, to remind us of ourselves. Now, there are no more comedy blockbusters. There are no more comedy stars. And perhaps, too, we have lost sight of the larger comedy of human frailty that the movies once provided for us.

A small, pink gleam of light. A few weekends back, I took my son to a screening of Oppenheimer in Manhattan. The movie was very good, but the highlight of the trip was seeing the dozens of Barbie fans dressed in all-pink getups in the theater lobby, there to share in the collective joy of a genuine movie phenomenon. Audiences were turning out in droves to see a movie with no superheroes, no explosions, no spacecraft, and few special effects. They were coming out, whether they knew it or not, to see a comedy. May there be many more Barbies in our future.

_____________________________

Paul Austerlitz’s Kind of a Big Deal is available now from Dutton.