My husband, a professor of electrical engineering by trade, is the kind of obsessive for which I have an affinity in my writing life. A refugee born in Latvia, John loves Latvian rye bread fervently. He eats Latvian rye several times a day and is unable to leave home without a five-pound loaf crowding the shirts and shoes in his carry-on. This bread, a talisman for his lost homeland, nourishes him physically and spiritually and it shapes his identity.

A couple of years after I published God in a Cup—which follows three young hotshots who were transforming the specialty coffee industry around the world and reports what took place in their interactions with coffee farmers, coffee traders and each other—as I pondered what next, John took the plunge and co-founded a teeny company marketing Latvian rye bread, online and in gourmet stores up and down the east coast.

John was now in the food business. I wrote about food. For the first time in our marriage, our professional worlds converged. Now when we entertained, which was often, Latvian rye bread was on the table front and center as a food and as a subject. I didn’t mind. To my surprise, our friends adored John’s bread.

I realized that feeling unequal to the task was part of the task.

One night I had a dream in which the title of my next book revealed itself: The Rye Bread Marriage. But I had no story, just the name.

As I contemplated this title without a book, two things were apparent: The story of Latvian rye bread, and John’s deep connection to it, would be central. Also, this book would be a platform for me to tell the story of John’s dramatic wartime childhood, something I had long wanted to do. I had no idea how these stories related to one another.

As to the marriage part of The Rye Bread Marriage? I played around with the idea of rye bread as a third partner in our union, a third spouse taking up room in our bed, but that idea didn’t go very far.

And so I decided to stick with what I knew. Despite my intimate connection to the subject, I figured I would do with rye bread as I had done with coffee: delve into the rye bread world, reporting on the history, focusing on a few key people who were changing the industry today Rye bread, however, was not a burgeoning industry in which I could identify and shadow a few key players who were changing the world. Bread, in fact, had been around in one form or another for 30,000 years. Its history was vast. As to Latvian rye bread? I didn’t speak Latvian and, except through osmosis, I knew little of Latvian culture. Until recently, I hadn’t even liked Latvian rye bread. (My conversion is one of the subjects I cover in my book.)

John and I traveled to Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. We visited bakers and bakeries. I interviewed people. John translated. I came home and wrote drafts describing the bread scene in post-Soviet Latvia. My agent, the always tactful Eleanor Jackson, said mildly, “I don’t think you’re there yet,” by which she meant, most of what I wrote was boring. The liveliness of God in a Cup wasn’t coming through. The material I wrote describing John’s and my adventures in Latvia was pedestrian, except one comic scene capturing John’s anxiety and our bickering about the map as we drove from Riga to the town where John was born to interview an oven maker.

I dug into files on my computer containing stories, written in the first-person and never published, about John and me, our marriage and our family. But how and where did these scenes from a marriage connect with the history of Latvian agriculture, the meaning of rye bread in Eastern Europe and the terror of John’s family fleeing Westward in war-time to escape the Russians? By now, I realized these three subjects were my themes. I had no idea how could I weave them together to make a cohesive story.

I enrolled in a few half day classes. Although I was writing nonfiction, I asked friends to recommend books teaching the basics of writing fiction. I had a sense that some of the problems I faced were craft-related. How to frame a story that has no obvious beginning and no end? How to build scene upon scene in order to create a clear and dramatic narrative arc? How to use sensory detail to add immediacy and specificity to people and places–this one I learned from re-reading Joan Didion.

I applied to and was accepted to a writing residency program, this one in Virginia, sponsored by the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts (VCCA).

VCCA changed my life. I met Sarah Pleydell, a novelist and theater artist, recently retired from the University of Maryland where she had taught creative writing for thirty years.

I had been a kind of lay teacher (neither analyst, nor trained writing teacher) at the certificate-granting psychoanalytic writing program for which I wrote some of those essays I found in my files. As a journalist with decades of practical experience, I was good at helping students figure out what worked and what didn’t, but I wasn’t a real writing teacher. Sarah was. When we returned home from VCCA, I asked her if she wanted to teach a workshop with me on imagery. I picked the subject of imagery because I didn’t understand it, but I sensed it was important to the book I was writing.

Our classes employed techniques Sarah had developed in her many years of teaching. We began by asking students to focus on the sensory, describing in language that was concrete and unadorned, a plant, a keepsake, an heirloom, a piece of chocolate. Metaphors and similes, not allowed. Memories and associations, not allowed. Focusing on the concrete removed students’ fear, and it set in motion a process that led in time to the spontaneous and unself-conscious production and retrieval of images from students’ unconscious minds.

I figured out that it was I as the narrator, who had to play the fool.

The way to learn, clearly, was to teach.

Working with students as they moved towards discovering the images that resided within themselves (another way of saying their own unique language), I realized that feeling unequal to the task was part of the task. I realized that I, like our students, could circumvent self-doubt, and discover untapped realms of feeling, memory and truth, by hyper focusing on the real. Block out the inner voice and in time the inner voice will shout back at you.

I started to understand the difference between the work I had done as a journalist and the work I was struggling to do now. What separated journalism and literary memoir was a kind of density of language. Imagery was a way of squeezing language in a vise, leading in time to a condensed form of language containing many layers of meaning. Understanding this helped me realize that the rye bread in The Rye Bread Marriage was one of my book’s subjects, yes, but it was also the metaphor that in time would weave my book together, enabling me to move back and forth among my subjects.

Slowly I opened myself to my own power as a writer. Letting go of my sense of literary insufficiency, led to discoveries related to structure and storytelling. I embraced the complexity and depth of my story. I gave myself permission to tell the story of my marriage, our marriage.

The book, ostensibly, and more than ostensibly, was about John. His life, which is far more dramatic than mine. His passion for rye bread. His eccentricities. But it was my voice, my inner life and perceptions in which readers would be immersed. I figured out that it was I as the narrator, who had to play the fool. It was I who had the lessons to learn. That learning became my narrative arc. (Had I cast John in this role, the book would have become an exercise in marital finger-pointing.) My opening up my role as narrator, led to an opening up of my understanding. I was able to see and describe my husband in his own terms, separate from me, without judgment, with compassion. I was able to see and describe myself in the same way. As I wrote about our marriage, I came to know our marriage in a far more nuanced, compassionate and accepting way. Psychologically and in a literary sense, I was changed, transformed, by writing this book, which finally, I suppose, is why any of us write: to know ourselves and the world anew.

__________________________________

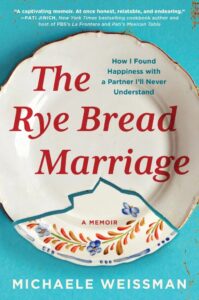

The Rye Bread Marriage: How I Found Happiness with a Partner I’ll Never Understand by Michaele Weissman is available from Algonquin Books, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.