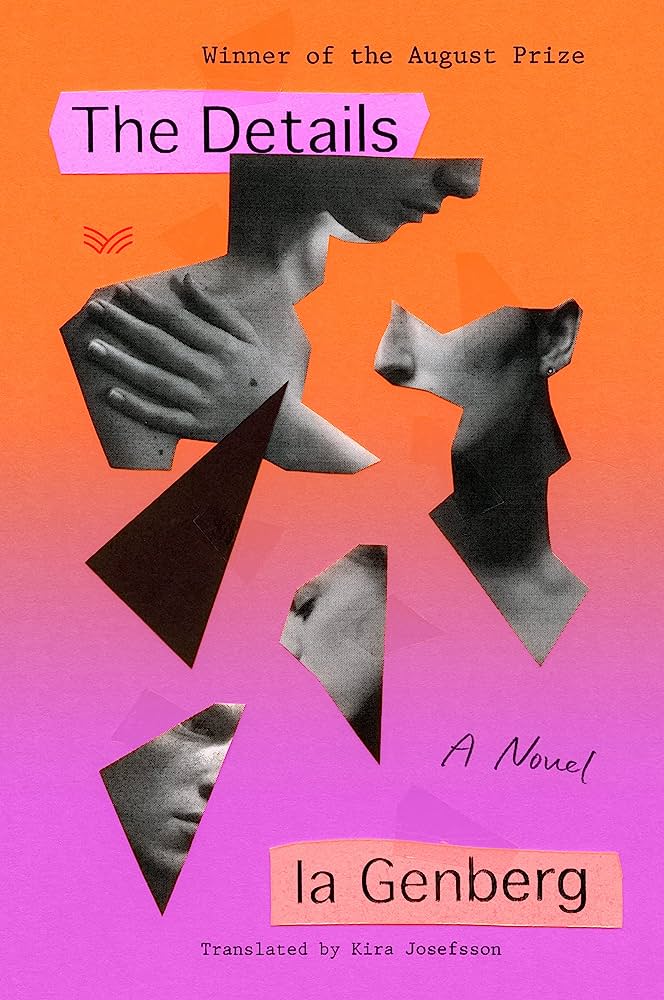

The following is from la Genberg’s English language debut The Details. Genberg began her writing career as a journalist and is the author of novels Sweet Friday, Belated Farewell, and Small Comfort, and one short story collection. She lives in Sweden. Kira Josefsson is a writer, editor, and literary translator working between English and Swedish. She was awarded a PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant and her work has appeared in Granta, Triple Canopy, Kritiker, and Arbetaren.

After a few days of the virus in my body I come down with a fever, which is followed by an urge to return to a particular novel. It’s only once I sit down in bed and open the book that I understand why. There’s an inscription on the title page, made in blue ballpoint and inimitable handwriting:

May 29, 1996

Get well soon.

There are crêpes and cider at Fyra Knop.

I’m waiting until we can go there again.

Kisses (they would prefer to be on your lips),

Johanna

It was malaria back then; I’d been infected a couple of weeks prior by an East African mosquito in a tent outside of the Serengeti and fell sick once we were home again. I was admitted to Hudiksvall Hospital and nobody could understand why all my results were off the charts; when at last they gave me the diagnosis, the doctors lined up to get a look at the woman with the exotic affliction. A fire blazed behind my brow, and I woke at dawn every morning at the hospital from the sound of my own breathing and a headache unlike anything I’d ever experienced before. Following our trip to Tanzania, I’d gone straight to Hälsingland to visit my grandfather on his deathbed. Instead I fell ill and nearly died myself. I spent more than a week at the hospital, but by the time Johanna gave me this novel, I was curled up in our bedroom in Hägersten, where they had taken me by ambulance via a liver biopsy in Uppsala. I don’t remember the results—there’s not much I can recall from that summer—but I’ll never forget our apartment, the book, or her. The novel disappeared inside the fever and headache, fused with them, and somewhere in that mix is the line that runs all the way to today, a vein of emotion electrified by illness and fear, which is what propels me to the bookcase on this afternoon to find that specific novel. Ruthless fever and headache, fretful thoughts crowding behind the eyes, the whooshing of impending distress: I recognize it all because I’ve experienced it before—the boxes of useless painkillers on the floor by the bed, the bottles of sparkling water I guzzle without any reprieve to my thirst. The images start rolling the instant I shut my eyes: horses’ hooves in a dry desert, dank basements full of mute ghosts, big vowels screaming at me—it’s the full standard menu of nightmares I’ve had since I was a small child, only with the added sprinkling of death and annihilation that is the territory of illness.

Literature was our favorite game. Johanna and I introduced each other to authors and themes, to eras and regions and singular works, to older books and contemporary books and books of different genres. We had similar tastes but opinions divergent enough to make our discussions interesting. There were certain things we didn’t agree on (Oates, Bukowski), others that left us both unmoved (Gordimer, fantasy), and some we both loved (Klas Östergren, Eyvind Johnson’s Krilon trilogy, Lessing). I could tell how she felt about a book based on how fast she worked her way through it. If she was reading fast (Kundera, all crime fiction), I knew she was bored and rushing to be done, and if she was going too slow (The Tin Drum, all sci-fi), she was equally bored but had to struggle to reach the last page.

She thought it was her duty to finish a book she’d started—just as she finished all her courses, papers, and projects. There was a deep-rooted sense of obedience in her, a kind of deference to the task at hand no matter how hopeless it might seem. She must have gotten that from her parents, from their creativity and unflappable dedication. In her view this commitment to completion allowed her to enter the future unencumbered, a way of maintaining what she called “a clean slate.” Life, in Johanna’s world, was lived in one direction, and that direction was forward, only forward. It’s how we differed from each other: I rarely completed anything big. After a year of temping in various Pressbyrån convenience stores, I enrolled in multiple university courses, all of which I would end up either dropping or deferring to the future, until I started to write more seriously. And not even at that point, when I’d resolved to dedicate myself full-time to becoming an author, did I manage to follow the path I’d laid out for myself. Instead I spent my days strolling around Aspudden, Mälarhöjden, Midsommarkransen, Axelsberg. In this era the neighborhoods on the city’s outskirts still had a certain seediness to them, with motorcycle clubs and tattoo studios and dim video rental stores with tanning beds. The subway stations were dank and dirty. All manner of people lived side by side, white-collar workers who went to work with briefcases in hand, artists who rented cheap studios in the industrial areas, junkies whose drug dens were regularly raided by the cops, old men with leathery skin who spent all day drinking in the town squares; these people all lived alongside one another in the three-story buildings that lined the winding main streets. These buildings housed cramped storefronts that sold foreign spices and simple restaurants with brown interiors where I’d sit in a corner, an empty plate on a plastic tray in front of me as I finished the dregs of my light beer while watching the other early afternoon patrons. There’d be a notebook in front of me, paired with a carefully selected pen, but I rarely made use of these implements. I might have given the impression of being dedicated but I was not, and the book stack on my nightstand always included one or two titles I’d abandoned midway through. I preferred books with a pull so strong I couldn’t get out. It was the same way with most things in life and as a result my responsibilities were few, perhaps too few. In fact I’d rarely encountered a responsibility I didn’t reject. This general principle didn’t make for any “clean slates,” and I assume that Johanna could only view my inherent inertia as a challenge. There was something about her speed and enthusiasm that gave me a bit of velocity, made things happen. Maybe this characteristic was what made me feel so safe in our relationship: she had started on me and wouldn’t give up. She wasn’t going anywhere; she’d never yield to an impulse to leave. I relaxed and surrendered. She was so thorough, so affectionate and loyal. Would breaking up ever occur to someone like her? No, I thought. No, never.

The book in my hand is The New York Trilogy. Auster: hermetic but nimble, both simple and twisted, at once paranoid and crystalline, and with an open sky between every word. On that point we agreed, Johanna and I, and a couple of weeks later, when the fever subsided, I read it again, now looking for flaws. I wanted to find out if the series was in fact obvious or boring but not a single thing was off about it, and soon thereafter I read Moon Palace and was again spellbound. Auster turned into a true north of mine when it came to both reading and writing, even after I forgot about him and stopped reading his new books as they came out. His discerning simplicity became an ideal, initially associated with his name though it endured on its own. Some books stay in your bones long after their titles and details have slipped from memory. When I finally went to Brooklyn for the first time, I looked up his address as if it was the most natural thing to do. It was a couple of years into the new millennium, and Johanna had long since left me for someone else, a sudden and brutal departure, stone-cold. By the time I was staring at the stoop of the brownstone where Paul Auster and Siri Hustvedt lived their lives and wrote their books, I was in a serious relationship with a man who in that moment was eating pancakes with my daughter at a nearby café. The multiple folded properties of time made it so that I could hear Johanna say something about chance, something I wouldn’t understand until much later, made it so that we both could think that we saw something moving behind the curtains on the top floor.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Details. Reprinted with the permission of the publisher, HarperVia, an imprint of HarperCollins. Copyrighted © 2022 by Ia Genberg. English translation copyright © 2023 by Kira Josefsson.