No children responded to my essay on the “adult problem” with kids books, somewhat proving the point. Adults aplenty chimed in, many of them people who work in children’s lit and who had good and interesting things to say that I appreciated learning about. Some others wished to point out that reviews of kid’s books do exist (I mean yes, but do children read the Wall Street Journal?), though most are more so recommendations; to date, the only truly critical (in the theoretical sense) review I recall seeing was this pan of Meghan, Duchess of Sussex’s, The Bench from Andrew Hagan at the London Review of Books.

I’m very happy that the discussion about what a kids’ book is or can be let me briefly aboard before continuing on its way, but wanted to take up the opportunity to ~curate~ a few books that might be described as “weird”—in the sense that they ignore common rules about what a children’s book has to do, or escape the kind of nostalgic or moralistic viewpoint that pervades a lot of new books. I offer them with the steep disclaimer that I am an adult!! Kids have been consulted where possible, but I’m blinkered by the same hubris that makes the rest of us so deeply uncool in kidland. I’ve also skipped the obvious ones: all other Jon Klassen, the Julia Donaldson oeuvre, Where The Wild Things Are, etc., and am limited to English-language books (though I’d love to hear about non-English hits).

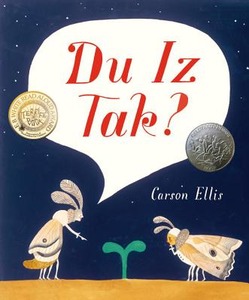

Carson Ellis, Du Iz Tak

Strictly speaking, this book can’t operate on an adult level because the dialogue is all invented (a sort of Flemish-Germanic gibberish). Some insects crowd around a green shoot, things escalate, questions are asked, and the ball is really in the kids’ court to figure out what the heck is going on.

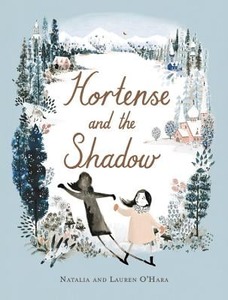

Natalia O’Hara, Hortense and the Shadow, illustrated by Lauren O’Hara

Hortense is aggravated by her shadow, which follows her everywhere. She imagines that her shadow hates her as much as she hates it until a dark night in the woods, when she is set on by bandits. BRING ON THE SHADOWS.

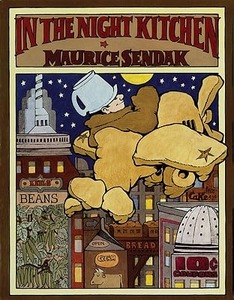

Maurice Sendak, In the Night Kitchen

As a kid, I remember finding this one in the library and marveling at Mickey happily skipping through the kitchen with a bare butt to help the night bakers with their batter. The book has been challenged for the aforementioned bum, though it’s more of a vibes kind of story that offers no judgement, no position, just classic Sendak.

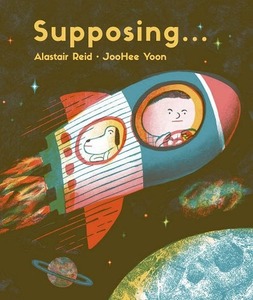

Alastair Reed, Supposing…, illustrated by Joohee Yoon

This is a very Kraussian book, originally written in 1960, and consisting really of odd premises (“SUPPOSING I sailed around the world and when I was a mile from my hometown, I just turned the boat and sailed round again the other way…”). Actually how my son talks a lot of the time.

Jon Scieszka, The Stinky Cheese Man And Other Fairly Stupid Tales, illustrated by Lane Smith

You heard Sciezka (“Sheska”): fairly stupid tales that kids have loved for decades (Mac Barnett is a big Sciezka fan).

Sophie Dahl, Madame Badobedah and Madame Badobedah and the Old Bones, illustrated by Lauren O’Hara

Mabel is extremely An Only Child, living in her parents’ bed and breakfast on the English seashore, and generating conspiracy theories about guests in lieu of having other kids to play with. When Madame Badobedah comes to stay, Mabel figures she’s a diamond thief, based on her intense luggage and weird accent, and the two eventually learn to operate in the same bizarro reality, despite being very old and very young, respectively.

Joanna Cole, Bony Legs

An Anglophone take on Baba Yaga, Bony Legs is a story about a girl, Sasha, who sets off through some very dark woods and stumbles on a witch’s cottage. The witch asks her to bathe in preparation for being eaten, and some kind characters help her escape the bathroom with some odd but satisfying tools: a comb that turns into a row of trees, a mirror that turns into a lake, and a pat of butter that allows her a silent escape through the witch’s creaky gate. Looking at this as an adult, in its strange two-color print format, it’s creepy as heck, and still just as satisfying to read as when I was a kid.

Ruth Krauss, Minestrone

From the master, an absolute trove of strange ideas and little narrative motors that putter through a thought and onto something completely different on the next page.

Wolf Erlbruch, Duck, Death and the Tulip

One day, Duck finds he has a new companion: Death, a skeleton in a robe. Duck asks questions about what happens after you’re gone, and Death explains that things continue on for the rest of the world. There’s anxiety and worry, but when Duck dies, Death lies her on the river and watches her float away with a tulip on her chest. That’s all, but of course that’s everything.

King Bidgood’s in the Bathtub, Audrey Wood, illustrated by Don Wood

Why would a king get out of the bath when he can eat there, dance there, fish there? That’s the challenge in King Bidgood, which is some weird sh*t indeed, and concerned primarily with getting the old monarch out of the tub.

Heckedy Peg, Audrey Wood, illustrated by Don Wood

A witch turns a woman’s children into food, and she has to correctly guess which food is which child, or she won’t get them back. Also they’re named after the days of the week. What?! Yeah, I don’t know either. Big thumbs up from Lit Hub, however!

Mem Fox, Hunwick’s Egg, illustrated by Pamela Lofts

All the animals in the outback think Hunwick is a bit odd for spending so much time tending to an egg that never hatches. That’s because the egg is a rock. Hunwick kind of knows and doesn’t care? Odd story, no visible moral thread, my kids are fans. (See also: Where The Giant Sleeps)

Minh Lê, Lift, illustrated by Dan Santat

Props to Minh Lê for a story that leaves a lot lot lot of room for a young reader to fill the holes around what is happening when Iris saves an old elevator button panel from the bin and installs it on the wall of her bedroom. Dan Santat is a brilliant illustrator who manages to create really rich visuals that bring wordless ideas to life, but also leave room for kids to see things into the pictures.

Mac Barnett, Jack at Bat, illustrated by Greg Pizzoli

An early reader book that exists entirely in the fantasy camp of Mac Barnett’s brain, Jack at Bat is half-nonsense and half a documentary of what it’s like to try and coach children at Little League. It’s all “Don’t swing that bat, Jack! Don’t swing that bat!” until the Ladies (who are playing the Brats) need a pinch hitter, and then everyone wants Jack to pick the bat up.

Abby Hanlon, Dory Fantasmagory

Dory is the youngest kid in her family and alternates between feeling put out that she’s excluded as the baby, and absolutely doubling down on her weird behavior: housing an ever-expanding crew of imaginary friends and villains (including Mr. Nuggy, a fairy godmother whom she calls on a banana), zoning the hell out of whatever she’s supposed to be doing and instead making horrendous messes, and creeping out her family. This one is an early chapter book, and Dory is in school, but I have it on good authority that toddlers cackle hard at the jokes. Get yourself downtown to TubTown.

Jon Klassen, The Skull

A skull and a girl become best friends, and defeat a headless skeleton.

Zoe Foster Blake, No One Likes a Fart, illustrated by Adam Nickel

This one has become a classic of the Australian Book Week in schools—from the bush to the sea, Aussie children love nothing better than to dress as plump fart clouds.

Vivienne Chang, This Is Not My Home, illustrated by Eughenia Yoh

How can a kids’ book show alienation, culture shock, and the push-pull of being an immigrant? I don’t know, but Vivienne Chang pulls it off in this book about Lily, a girl who travels with her mother (back) to Taiwan when her ah-ma (grandmother) gets sick. There, she gets that it’s her mother’s home, but not hers, at least right away.

Laura Dockrill, Angry Cookie, illustrated by Maria Karipidou

Much of this book is yelling, and my kids love it.

Trent Jamieson, The Giant and the Sea, illustrated by Rovina Cai

Hesitated about putting this one on the list, since it is dark in a climate-doom kind of way. However! My daughter goes for the slightly gloomy and prophetic story of the giant who warns a child on the beach that the ocean is rising, the ocean is rising.

Molly Idle, Witch Hazel

Let’s end on death, shall we? In Witch Hazel, the child, Hazel, spends time with the elderly Hilda, who tells her stories about the past. When Hilda disappears later in the book after taking to bed for a couple of pages, Hazel keeps Hilda’s stories with her. This actually feels a lot how death works for children—the people who are gone become stories that endure even as the original memory disappears.

Do let us know what we’ve missed! What flies under the radar? What do others need to know about?