Time is the substance I am made of. Time is a river which sweeps me along, but I am the river; it is a tiger which destroys me, but I am the tiger; it is a fire which consumes me, but I am the fire.

Thirty-seven years ago today, Jorge Luis Borges, Argentina’s most famous literary son, died in Geneva at the age of 86.

The publication of Labyrinths in 1962 marked the first time most English-language readers were exposed to the work of this mysterious giant of Latin American letters.

To mark the anniversary of the great man’s death, here’s a look back at a 1962 New York Times review of this groundbreaking collection.

*

“The myth of Jorge Luís Borges has, for at least twenty years, caught at the minds of people interested in Latin American literature. This man, say his admirers, is not only the great South American writer but great in terms of any geography. A difficult writer? Too erudite? Only to the ordinary. On the other hand, arcane, over-subtle, an arrogant intellectual who does not bother to make himself understood, ‘an abstruse dweller in an ivory tower’—these are the phrases that the ordinary, including some of his own countrymen, shoot back.

Visitors to Buenos Aires who tried to plumb the mystery for themselves had little luck. Borges was out of town, or in Paris, or indisposed. He began to sound like an Ezra Pound, wrapped by preference in his chosen isolation. He could be read in his own Spanish, in French, in Italian, but not in English. Meanwhile, aspiring students who wrote for literary journals tried to break the barrier by translating bits and pieces.

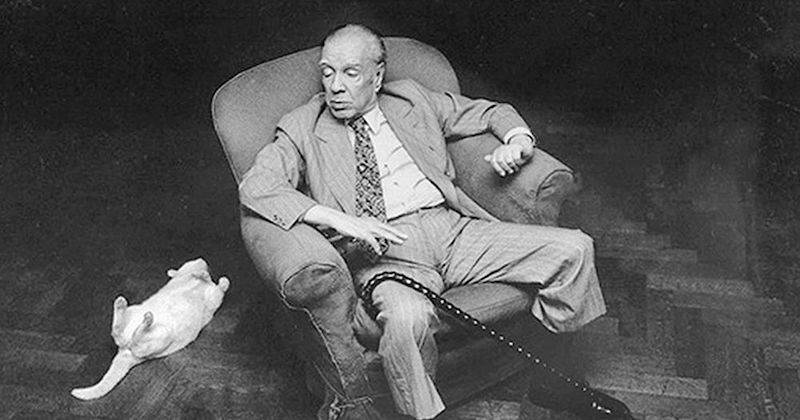

Now for the first time his work appears here between book covers, just after the man himself had appeared at several American colleges, including Columbia. To a certain extent the mystery is mitigated. Those who heard him amid the crowded enthusiasm of students at the Casa Hispánica got a wistful impression of a giant bound in dusk. An increasing eye illness, growing worse with the years, has blinded this gifted writer to all but light and darkness. He looks at the world, but does not see it, and takes refuge within his own extraordinary mind.

This may explain in part why he does not give of himself easily, or at length. All that there is of him comes in short bits, compressed, concise, graven like a fine intaglio. Except for a few collaborations in which another writer furnished the staying power, Borges has written only miniatures—essays, parables, short stories. If you want to know Borges, yours must be the effort.

He is well worth it.

They recall Sartre and Camus, Kafka, Pound and Valéry. An extraordinarily well-furnished mind, within which Borges moves and from which he draws at will, is obviously one source of his strength. Not only does he draw from the best of his contemporaries but also from such older greats as Poe and the philosophers, the cabalists, the by-gone Greeks of Alexandria. This is a scholar of no mean depth. Only he could write the imaginative tale of what, with his power of imagination he might have done had not bad eyes and uncertain health forced him to pack so much meaning into so concise a set of miniature forms.

The essays and the parables are less immediately attractive than the short stories, but they too catch at the reading mind and force it to think. The Borges detective stories are lean and haunting, the bare bones of plot and detection told with some secret quality of suggestion, some skill of prose so upsetting that they slide the most causal mind unwittingly off balance. Read ‘Death and the Compass’ at midnight, and it will never leave you. As for the ‘Library of Babel,’ it will lead you to look twice at the new library of the United Nations to make quite sure that this one has not yet slipped into the world of the Borges sane-insane.

“…it [is] finally possible, after all these years, to give Borges his due and to add North Americans to his wide public.”