“Don’t worry about the class. You just concentrate on getting well. The class will still be there when you come back.”

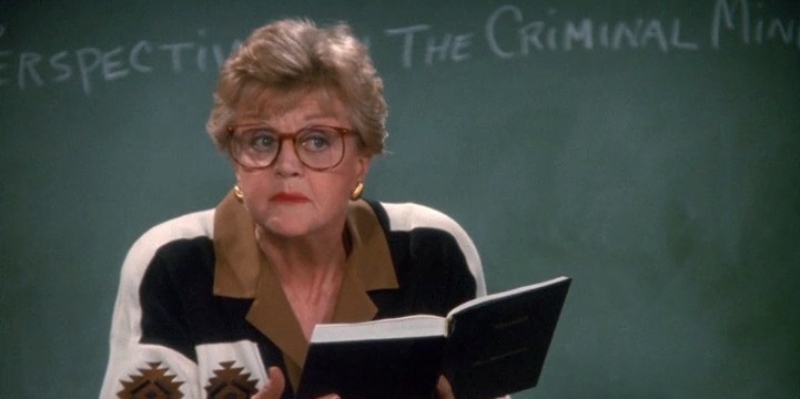

Though this statement might read like an email from a kind faculty member to a student sick with COVID-19, it actually hails from a much more historically distant source: the hit television series Murder, She Wrote (1984-1996). In this episode, the show’s heroine—the substitute teacher-turned-mystery writer and amateur sleuth Jessica Fletcher—takes on a new role as a criminology instructor at Manhattan University.

On the first day of classes, a bright young student named Roslyn is violently mugged on campus. Despite only knowing Roslyn for a few hours, Jessica rushes to her hospital bedside, listens to her concerns about safety on campus, and reassures her that the class will be waiting for her when she gets back.

Murder, She Wrote (MSW) has ignited much commentary over the years—most recently following Angela Lansbury’s death in October, followed just nine days later by that of Ron Masak (who played the sheriff Mort Metzger). Critics have noted Jessica’s status as a “feminist icon” and “anti-ageism heroine,” as well as the show’s unique coziness and soporific effects, due to the idyllic seaside setting of Cabot Cove, Maine, and the comforting fact that Jessica always cracks the case.

Lately, however—no doubt due to my own role as a relatively new college professor—I have become fascinated by the moments in which Jessica appears in the classroom. Jessica taught English at Cabot Cove High School for several decades and teaches and guest lectures at various institutions (high schools, colleges, women’s prisons) throughout the series. In MSW’s classroom-centric episodes, Jessica fosters some of the best practices of what scholars of teaching and learning call critical, feminist, or radical pedagogy. Jessica creates an inclusive classroom environment, fosters critical and creative thinking, affirms her students’ work, and cares for her students both in and out of the classroom.

I am not claiming that MSW is any kind of politically radical show. It is about the whitest show one could imagine, oftentimes with cringe-worthy treatments of race and ethnicity and a “tendency to exoticize non-Black people of color.” Much of its politics has, of course, not aged well. I now wince, for instance, at the thinly veiled racist rhetoric surrounding the Cabot Cove townspeople’s collective panic at Jessica’s move to “dangerous” New York City in Season Eight.

Rather than wielding her power at the front of the room, Jessica focuses on building camaraderie and trust with her students.

Nor am I claiming that Jessica is a model practitioner of critical pedagogy. Advocates of student-centered learning might note that Jessica often lectures, and there is a scene in Season One in which she theatrically wields a fake gun at the end of a class—a detail that now reads as especially unsettling given the epidemic of school shootings in the US.

Nor is Jessica, a bestselling author, subject to the financial precarity or career uncertainty that other faculty members in her position—as far as I can tell, a part-time lecturer role—are subject to as colleges and universities increasingly rely on (and exploit) adjunct instructors. (Jessica’s dean, on the other hand, offers her the department’s “plum course” and personally escorts her to her own office on the first day of class.)

And yet, Jessica’s approach to teaching, if far from a full embrace of liberatory pedagogy, is nonetheless compelling, especially from the vantage point of today’s “post”-COVID higher education landscape, in which some faculty insist upon a return to academic “rigor,” in which students (and faculty) who seek accommodations or content warnings are branded as entitled “snowflakes,” and in which institutional pushes for a “return to normal” exclude students and faculty with disabilities or other access needs.

(This is not to mention the all-out assault on DEI curricula currently unfolding in Florida, or the mounting evidence that social anxiety and trauma are at record highs among college students.) This landscape encourages faculty members to see students as “adversaries,” not “allies.” In this context, Jessica’s pedagogical approach feels all too urgent.

For starters, Jessica fosters inclusive learning communities. On the first day of her criminology class, she seems to know all of her students’ names (presumably without an electronic roster or pre-circulated ID photos!)—a detail that, while seemingly minor, is actually a crucial pedagogical practice that signals her commitment to recognizing, from day one, what bell hooks would call her students’ “presence.” Jessica is also willing to risk her own professorial authority in order to gain her students’ trust and foster collaboration.

When a student in her criminology class challenges her credentials because she is not a professional detective, she welcomes rather than bristles at the student’s critique. “No offense taken . . . It’s a fair question,” she tells him, before proceeding to prove herself through a series of Sherlock Holmes-style observations about him. Smiling, the student promises to give Jessica a chance. Jessica is willing to invite questions, engage with students’ critiques (even potentially insulting ones), and meet them where they are. Rather than wielding her power at the front of the room, Jessica focuses on building camaraderie and trust with her students, inviting everyone to contribute to the shared project of building a dynamic and flexible classroom community.

Moreover, Jessica’s pedagogical approach—controversial among her criminology colleagues—centers on critical thinking and creative problem-solving rather than fact memorization (what Paolo Friere calls the “banking” model of education, or what Kevin Gannon refers to as the idea of “knowledge as a fixed commodity”). Jessica tells her students, “The crime scene is more than just an inventory of fibers and hair and samples of ballistics. It tells a story of passion or jealousy or anger.” Though a male colleague reprimands her for not focusing on the “facts,” Jessica urges her students to understand broader narratives and to approach problems from multiple perspectives: “Suppose today we put ourselves in the shoes of the murderer. How does he think? How does he act?” (We should also note her use of the collective “we” and “ourselves” in this moment—words that signal Jessica’s eagerness to learn alongside her students). For Jessica, learning goes far beyond “inventory.”

Jessica also affirms her students’ work—particularly, viewers might note, that of marginalized students. When she teaches at a women’s prison in Season Two, she praises several of the students’ short stories. “You’re a very talented young lady,” she tells one incarcerated woman. “I thought your story had a great deal of sensitivity and skill. I know it doesn’t come easy.”

When Jessica learns that one of her criminology students—a poor man with a criminal record—is an aspiring writer, she reads his work outside of class and agrees to work with him: “You show a potential way beyond your years, and you have talent, and talent should be encouraged.” Jessica amplifies the voices of students who have otherwise been silenced throughout their educational careers.

While many faculty wield their “pedagogy [as] a weapon,” Jessica resists course policies or bureaucratic barriers that impede learning. When Roslyn, the student who was mugged on campus, signals her fear about coming back, Jessica does not pressure her to return but instead reassures her that the class will “still be there” whenever she is ready. Jessica displays what Cate Denial calls a “pedagogy of kindness.” As Denial writes,

Why did I require students to jump through hoops to prove that they deserved an extension on a paper? Why did I dock points if my students missed three classes in a term? . . . We as teachers have the ability to insist that individuals matter. We have the means to hold a line, to see the student without shelter—or food, or safety, or a laptop, or an internet connection, or health, or confidence, or a support network—as someone who matters exactly as they are […].

Jessica again resists exclusionary policies when she accommodates a student whom the dean tells her to “stay away from” because he has a criminal record and does not have the “grades or background required” to register for the course. “He’s trouble,” the dean insists, and chides Jessica that her “care” for her students “can work as much against [her] as for [her].” But Jessica insists that the student is “bright and dedicated and . . . worth a second chance.” Jessica sees her students as human beings worthy of trust and empathy rather than inferiors who need to be closely monitored and disciplined.

Jessica also cares for her students outside of the classroom. In one episode, she tutors a student after hours to help him pass the NYPD sergeant’s exam. At the women’s prison, she commits to doing “everything in [her] power” to help a student at her parole hearing. Jessica models the kind of personal pedagogical approach that hooks describes: “[M]y teachers made sure they ‘knew’ us. They knew our parents, our economic status, where we worshipped, what our homes were like, and how we were treated in the family.” For Alison Mountz et al., this kind of care reflects nothing short of a “feminist politics of resistance” to the “neoliberal university”: “[C]ultivating space to care for ourselves, our colleagues, and our students is, in fact, a political activity when we are situated in institutions that devalue and militate against such relations and practices.”

To be clear, Murder She Wrote is not a show about teaching, nor is it the text to which teachers should turn for ideal models of engaged pedagogy. And yet, the series does offer powerful glimpses of some of the real affordances of a pedagogy premised on care and compassion. As a teacher, Jessica helps incarcerated women feel their voices are valuable, supports a female student who feels unsafe on campus, and makes space for all kinds of learners—even “trouble[d]” ones—to succeed. For me, MSW’s most moving moments are found not at the crime scene, but in the classroom.