It was the spring semester of 2009, and I was alone in my dorm room, looking over notes for my film class on Spike Lee, trying to connect Malcolm X and Mo’ Better Blues in a way that felt entirely original. Blu & Exile’s Below the Heavens played as loudly as my second-generation MacBook would allow. I was a newly minted double major in English and Africana Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, nearing the end of my junior year.

I lived in the W. E. B. Du Bois College House: a dormitory at the edge of Penn’s campus named for the philosopher, sociologist, novelist, and poet. Though Du Bois himself had a truly harrowing time as a faculty member at the university back in 1896—he was allowed neither to have an office nor to teach students during his time at Penn—the dormitory was as robust a reflection of human life on Earth as one might hope to see on a college campus: students from all over the world, mostly black and brown, choosing to live in this place for its emphasis on social justice, the arts, and the celebration of cultural practices from across the African diaspora.

It was in this uniquely boisterous environment—surrounded by the charismatic boasts of hip-hop and dance- hall, the steel boom of soca and kompa, hallways filled with laughter and conversation—that I looked up from my notes to see a missed call from a California area code. Whoever it was had left a voicemail message. I turned down the music and put my ear to the phone. The voice on the other side belonged to James Kass, founder and executive director of the nonprofit poetry organization Youth Speaks.

Without much in the way of lead-up, and with a tone of palpable joy in his voice, James had asked if I would be interested in reciting one of my poems at the White House. I would have to agree to a thorough background check and be ready to go within the next week.

I can still remember looking at the phone, and then at the ceiling, and then at the desk across from my twin bed, covered with textbooks and printed notes. For a while I just sat there, frozen. I returned James’s call, and after what might have been the shortest round of small talk in my entire life (“Hi, James, it’s Josh—got your message. What’s going on now, exactly?”), we got to the matter of the voicemail.

James told me that if I was interested, I would have the chance to recite my original work in the East Room, alongside various literary and dramatic luminaries. He had no other information to share at the time (which was fine with me, given how strong the opening pitch was) and instructed me to stay by the phone. In a few minutes, I received a call from Stan Lathan, who laid out all the details.

Without much in the way of lead-up, and with a tone of palpable joy in his voice, James had asked if I would be interested in reciting one of my poems at the White House.

At this point, I had known Stan personally for a little over a year, though I was familiar with his work from a childhood spent watching it with family and friends. Over the course of his career, he had amassed directorial and production credits for Def Comedy Jam, Def Poetry, Sister Sister, and Martin along with numerous other black American televisual touchstones. In 2008, he produced an HBO documentary called Brave New Voices, which featured poetry slam teams from across the country as they were headed to an international youth slam competition by the same name.

Back when I was a freshman at Penn, I’d earned a spot on the Philadelphia team that won the 2007 Brave New Voices title: a mélange of college students from Philadelphia-area schools and teenagers from around the city, with styles ranging from lyric poetry straight from the page to verses that called upon the cadence of the hip-hop styles that raised us. In 2008 we were set to return to BNV, hoping for a repeat performance. Weeks before the trip, we learned that the entire competition, as well as the road leading up to it, would be filmed by HBO. Our team was one of five that would be featured in a soon-to-be-televised documentary.

For the better part of three months, the cameras followed us everywhere: across our respective campuses, and even to the neighborhoods we grew up in. They recorded our weekly practices, as well as our fundraising efforts on the streets of West Philadelphia: hours spent performing poems in shifts at the intersection of 40th and Walnut, right in front of the movie theater, my red New Era fitted cap left upside down on the sidewalk to collect cash donations from passersby.

After the Brave New Voices documentary aired, Stan helped create all sorts of other opportunities for me to share my work with the world. Three months before the White House event, he invited me to perform at the 2009 NAACP Image Awards in Los Angeles. Now he was inviting me to DC, only this time I would be the only one onstage. No friends or teammates—just me, and the microphone, and one of the hundred poems I had scrawled into various black-and-white notebooks over the years.

According to Stan, for the event in question, An Evening of Poetry, Music, and the Spoken Word, I was to recite a new, original work—a two-minute poem, to be exact—on the theme of communication. The audience would include President Obama and the first lady, Michelle Obama. I thanked him for the opportunity and hung up the phone.

After the call, I ran laps around my dorm—and not my dorm room, to be clear, but the entirety of the Du Bois College House—for the next ten minutes. It took me a day or two, but I eventually settled on the poem I would read: “Tamara’s Opus,” an ode to my older sister. The subject of the poem was my relationship with Tamara, who is deaf, and by extension my relationship to American Sign Language, which I had struggled to learn as a child. Given the theme, and the stakes of the moment, I knew there was no other poem I could share from that stage. If I had an audience with the president, even if it was just for two minutes, this was the message I wanted to leave with him.

The trip to DC was surreal. I had never ridden an Amtrak train before, and this ticket had come courtesy of the executive branch. I reclined my chair and tried to take a nap, but was too anxious. And so, as has become my custom during the decade since that trip, I rehearsed my poem, backwards and forwards, as many times as I could.

The version I would be performing at the White House had been edited for time and was now two minutes flat (as opposed to the three-minute-fifteen-second version of the poem I’d performed during a showcase at Penn the year before). The new version was somewhat unfamiliar, but still felt true to the spirit of the original. To this day, “Tamara’s Opus” stands out among all the poems I have ever written—not only because it served, in many ways, as the beginning of my career as a professional writer, but because in that moment, running the poem back and forth from my seat, I learned something fundamentally true about why being a poet was important to me, and why I would have to engage with this art form for the rest of my life.

It left me nowhere to hide. It forced me to confront my guilt, my pain, and all my shortcomings. It demanded that I give an account.

At Union Station I was greeted by handlers, who introduced me to two other performers. It was my first time meeting Mayda Del Valle, the former Nuyorican Grand Slam Champion, whom I recognized from videos online, and a welcome reunion with Jamaica Osorio, whose slam team from Hawaii had won Brave New Voices the year before (and would win it again later that year). The handlers drove us all to the White House in a large black Escalade.

What could I ever accomplish that would top an audience with world leaders and standard bearers in my chosen field? I had gotten the chance of a lifetime. What would come next?

We arrived at the front gates, where we met a few of the night’s other performers: James Earl Jones, Michael Chabon, Esperanza Spalding, and Lin-Manuel Miranda. After having our IDs checked by agents at the entrance—I don’t know for sure that they were Secret Service, but they looked the way Secret Service agents looked on television—we spent an hour or so on a tour of the White House.

After the tour, during rehearsal and a brief sound check, I listened to Jones deliver a monologue from Othello, marveled at the speed and grace of Spalding’s bass playing, and witnessed Miranda deliver an extended verse in the persona of Alexander Hamilton (this would eventually become Hamilton’s opening number). An hour or so later, everyone dressed and went backstage. We recorded audio of James Earl Jones saying “Luke, I am your father.” Lin and I started a freestyle cipher that pulled various objects from the rehearsal space into its orbit: “black suit / and a silver tie / hit ’em with the verses that vivify / the room / weary blues take flight from the villain’s mind / made it all the way to 1600 Pennsylvania / classic like Othello and Ophelia / Dizzy and Mahalia….”

When the event began, the sense of freedom I felt backstage gave way to undeniable anxiety. A sense of heaviness fell over me. Though I had already run the poem hundreds of times, I felt that I was still unprepared for the moment in some deeper sense: an amateur, writing poems in a weathered notebook I had brought from home. And now my mother was seated in the front row, to the direct left of Joe Biden: the youngest of seven children, and the first to go to college.

As a girl growing up in the South Bronx, she loved the viola, and even played at Carnegie Hall as a teenager. We never had much in the way of material things. Within the bounds of our household, my mother stressed two matters above all else: faith and the importance of formal education. Nothing will ever be handed to you, she reminded me time and time again. So work as hard as you can, and be ready to stand when your moment arrives.

When my White House moment arrived, I was announced by a voice without a face, soaring through loudspeakers I couldn’t see: “And now, the spoken word poet Joshua Brandon Bennett.” I ascended the stairs to the stage, barely breathing. I looked out at the crowd, smiled to my mother, and unbuttoned the black suit jacket she had bought for me the week before. I closed my eyes and focused on the image of my sister’s face:

Tamara has never listened

to hip-hop

Never danced

to the rhythm of raindrops

or fallen asleep to a chorus of chirping crickets she has been Deaf

for as long as I have been alive

and ever since the day that I turned five

my father has said:

“Joshua. Nothing is wrong with Tamara.

God just makes

some people different.”

And at that moment

those nine letters felt like hammers

swung gracefully by unholy hands

to shatter my stained-glass innocence

into shards that could never be pieced back together or do anything more

than sever the ties between my sister and I….

I still remember her twentieth birthday

readily recall my awestruck eleven-year-old eyes as I watched Deaf men and women of all ages dance in unison to the vibrations

of speakers booming so loud

that I imagined angels chastising us

for disturbing their worship

with such beautiful blasphemy.

Until you have seen

a Deaf girl dance

you know nothing of passion.

I recited the entire poem from memory, pulling American Sign Language into my performance as I told the story. After reciting the final line, I took a breath and left the stage. The East Room was a vision. Saul Williams, the actor and poet, and Spike Lee (in a truly unexpected turn) were right there in the audience, cheering me on, alongside college students from Gallaudet (the nation’s first university for deaf students), Georgetown, and American University, signing and singing their approval. It was the most important performance of my life to that point.

When it was over, Secret Service agents (I checked to make sure this time) walked the entire group of performers through the front gates. With my mother by my side, I hailed a cab at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue.

Lying in bed, I felt a sudden wave of disappointment. I had loved to write, to perform, for as long as I could remember, and never imagined those passions leading me toward anything like this; an occasion that felt like it was about something much larger than me as an individual poet. I was there—alongside Mayda and Jamaica and Lin and James and Esperanza and others—to represent the art forms we had committed our lives to. What could I ever accomplish that would top an audience with world leaders and standard bearers in my chosen field? I had gotten the chance of a lifetime. What would come next?

These were questions that would take me years to answer on terms that felt sufficient. But just for a moment, that night, the stress gave way to a kind of relief. The moment hadn’t been too big for me. With the people I loved most at my side, I shook off the weight of my fear. And flew.

______________________________

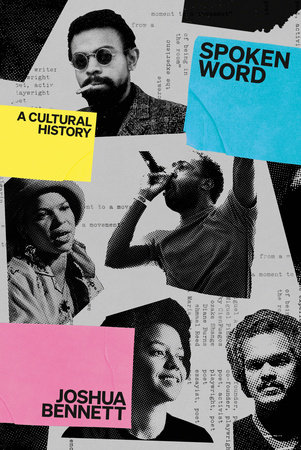

Spoken Word by Joshua Bennett is available via Knopf.