The following first appeared in Lit Hub’s The Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

One day, in the midst of working on my first novel in English, I was overwhelmed by a wave of frustration with my adopted language. With some fury, I knocked this out on the page and decided not to translate it:

我说我爱你,你说你爱自由。

为什么自由比爱更重要。没有爱,自由是赤裸裸的一片世界。

为什么爱情不能是自由的?

A few years later, when the novel was published, the Chinese text remained exactly as it was, though the rest of the book had been revised hundreds of times.

I used to write and think in Chinese ideograms. Then, at the age of 30, I switched to writing in English. But when I write in English, I don’t quite think in English. I have to self-translate. Self-translation is not like translation as we might ordinarily know it. It’s more difficult and involves the writer’s whole, lived experience. The process of self-translation and linguistic translation is like crossing a wild river from one bank to the other. To get across, you have to deal with treacherous weeds and hidden rocks and whirlpools of culture and concept. And the other bank is not always in view. But you swim on.

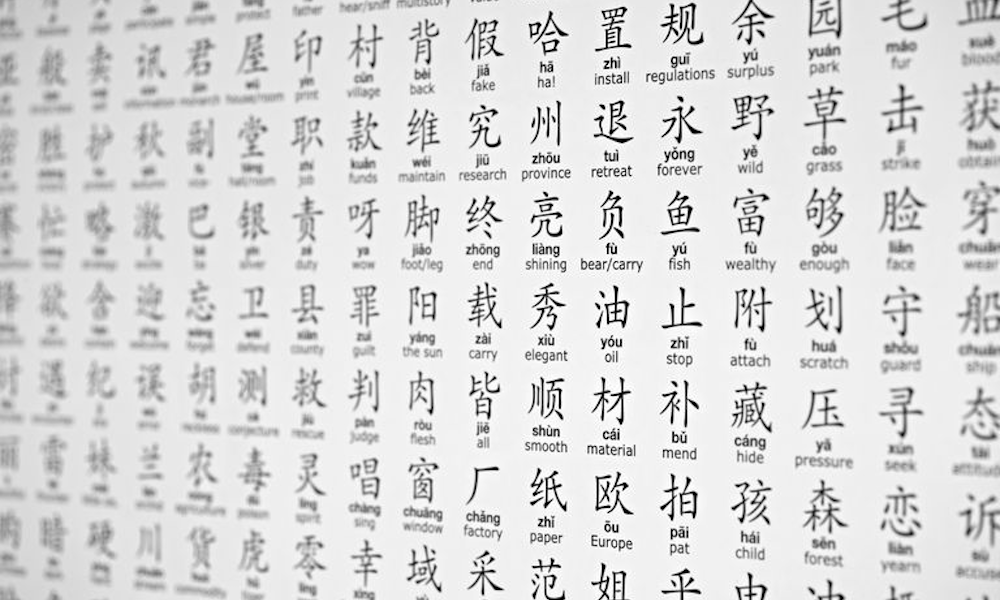

For a writer coming from an idiographic and pictorial writing system, this transition to an alphabetic system is complicated. Of the many differences between the two systems, the first and foremost is visual. To give a concrete example, in Chinese, a tree is 木 (pronounced mu). If you put two trees together, it becomes a grove—林 (lin). And if you put three trees together, it makes a forest—森 (sun). Perhaps because of its iconographic nature, Chinese writing is more condensed—each symbol holds more meaning than a word. It’s also nonspecific about time and action. If one reads a Tang poem and its English translation alongside, one quickly gets a sense of the difficulty of the translator’s task. All the basic structures such as subject, action, and specific time have to be projected by the translator onto the ideograms. There’s a beautiful simplicity in one tree being 木, two being a wood, three a forest. But such an imagistic mode of conveying meaning leaves the European translator floundering.

But I am not here to talk about untranslatability. On the contrary, I want to talk about the possibilities of translation. I especially want to discuss the layers of self-translation migrant writers have to undertake when they write in a new language and culture.

I especially want to discuss the layers of self-translation migrant writers have to undertake when they write in a new language and culture.

When I am beginning a novel, there are two fundamental things I need to establish. One is horizontal, the other vertical. The horizontal is the landscape. The vertical is the social space. These are the dimensions that allow my imagination to enter my novel and people it with characters. I know for certain that when I write in Chinese, landscape comes first. I must know if I am writing about a village or a city and whether it is an agricultural village made up of cultivated land and animals or a car-choked city full of workers and the newly rich.

Then the architectural elements come in—whether it is an apartment in a tall, modern building or a traditional courtyard. Characters are tied to their living spaces, and their development is tied to the changes in that space. So I construct everything around these two horizontal and vertical elements. The characters are depicted through their particular forms of language, be it their dialect or a common form of speech—in China, almost every region has its own dialect, and Mandarin is an official language that is mostly spoken in the northern part of the country.

These ways of constructing a story had hardly altered when I began to write in English after moving to Britain. But somehow, in English, I could not just depict a Chinese landscape or its living history as I had done in Chinese. This was not a mere matter of linguistic translation (which is hard enough) but of a deeper matter concerning the translation of the writer’s self. By “self” I mean that reservoir of memories and experiences that cannot be separated from cultural and political conditioning.

As a writer who has migrated from a culture far from the European tradition, what I must confront with the alphabetic language (in my case the English language) is the chasm of cultural differences mixed up with mutual ignorance of one another’s history. I cannot just wait to be understood. It’s up to me as the writer to build a bridge spanning this abyss. Maybe one day Westerners will wake up and realize the importance of Asian culture, open the first page of The Dream of the Red Chamber or The Tale of Genji. But until that happens, I must self-translate. I must convey my voice, culturally and politically, in a second tongue in order to influence my new readership. The way to do this is through the creation of a hybrid language. To self-translate, one has to hybridize language. Chinese concepts that naturally live in the world of ideograms must be recast in English idioms and syntax.

But to self-translate is to study what surrounds me in my present life and how it relates to my past experiences.

When I was writing A Lover’s Discourse, my most recent novel in English, the same elements—landscape and architectural living space—were decided before the story. Perhaps “decided” is not the right word. It is more that they chose me. The Regent’s Canal area in northeast London is the novel’s geographical setting, as is the ever-expanding immigrant scene. The winding, narrow English streets and the wet parks are the spaces my characters move about in. Along with those choices, I could not help but absorb the political atmosphere after the Brexit referendum. That naturally led to me putting another European country (Germany in this case) as a place of possible refuge for my two non-British Londoners. Would they move to Europe or return to Asia? Both were transplants: Where was their home? What could their relationship to Europe or Asia be?

When I thought about these themes, I could only write in a comparative mode. I kept comparing the sky and the water of England to the sky and the water in China. I kept comparing daily life in the uncertain political environment of Britain to daily life in China. I thought of the difference between a democratic society such as Britain and an autocratic one such as China. I thought of how the West’s ideology of the pursuit of happiness compares with the East’s pursuit of harmony. I translated my feelings into sentences and dialogue, putting them into the characters’ mouths and minds. My English sentences were tinted with a particular East Asian past: Confucian tradition and nostalgic romanticism fused with the sloganistic communist language. Although that past was not entirely present in my novel, it built the tone of the book, its voice. It’s in the voice of a female author from mainland China who has tried to adopt Western culture by living in it and conversing with it. That’s also how I wrote my previous novels I Am China and A Concise Chinese-English Dictionary for Lovers.

But to self-translate is to study what surrounds me in my present life and how it relates to my past experiences. The past is always the subtext and a strong ongoing memory. Since I have been living in this part of Europe, I am cut off from an agricultural life or a collective way of living. Still, I search for them in my foreign existence. Every day, my walks take me to the paths where English nettles and wild elderflowers grow. My wanderings frequently lead me along the canal’s rust-colored waters, either toward the west, to Islington and Angel, or toward the east, to the Olympic Park and the Lee River. I can’t remember at which point I began to see urban beauty in these decaying industrial remnants. It makes me think of the former glories of Britain now forever lost.

For a Chinese, this aesthetic is alien, but I have managed to grow into it. Like England’s cloudy skies, like baked beans on a breakfast plate, like pale faces and muddied boots. These facets of life have been in my routine since I arrived. So the characters in my Western stories live with these landscape elements, along with European and American politics. But where does China fit in? For me China lies everywhere and is beneath everything. China formed the mind’s eye that I carry with me, through which I view everything, coloring the world with shades and hues. I must bring it out through my writing. This is the self to be translated.

_______________________________

Excerpted from Letters to a Writer of Color edited by Deepa Anappara and Taymour Soomro. Published by Random House Trade Paperbacks.