The end of 2022 draws swiftly near, and with it the inevitable deluge of best-of lists. Have no fear; ours is coming. But first, and before things get truly hairy, we at Literary Hub wanted to take a moment to appreciate some of the books we’ve read recently that won’t be winning any new prizes or making a thousand lists—because they weren’t actually published this year. (Imagine that!) We live in a culture of hysterical newness, but luckily, books don’t expire—they have lives that stretch for months and years and decades after their publication. So to that end, are the non-2022 books we loved best in 2022.

*

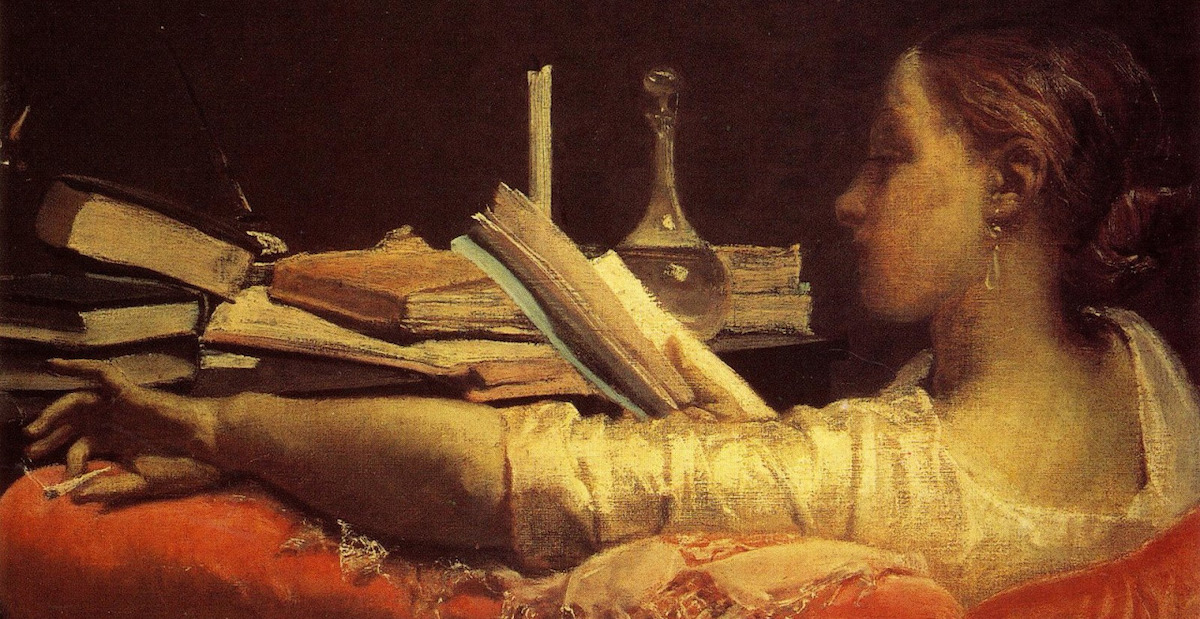

Laurie Colwin, Family Happiness (1982)

Reading a Laurie Colwin novel is sort of like watching a Nora Ephron movie. There is something deeply comforting about its familiar rhythms and its witty repartee. You are guaranteed a good story, typically one about misadventures in love. In Family Happiness, we meet Polly. Polly seems to have it all. She’s got a lawyer husband, cute children, a magazine-worthy home—and a lover on the side. Yup. Polly has always been the perfect mother, daughter, and wife; she is sick of contorting herself to fit into the spaces left by other people. In this affair, she finds refuge from the storm of her life. She finds the companionship and romance that her husband no longer offers her, but at what cost to her conscience? How can Polly be the person she truly wants to be? With this novel, Laurie Colwin puts daily family living under the microscope and asks cutting questions about sacrifice, the limits of love, and how to take the reins on a life barreling down the same old train tracks. –Katie Yee, Associate Editor

Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, Murray Silverstein, et al., A Pattern Language (1977)

I moved this year, and had occasion—though mostly theoretical—to dip in and out of this cult classic: an oddly poetic, somewhat radical guide to architecture and community building. Principles include limiting buildings to four stories (“There is abundant evidence to show that high buildings make people crazy.”), the placement of grave sites (“No people who turn their backs on death can be alive.”), and the importance of carnivals (“Just as an individual person dreams fantastic happenings to released the inner forces which cannot be encompassed by ordinary events, so too a city needs its dreams.”). The effect is like opening a jewel box, one which continues to surprise, delight, and invite the reader to reconsider their surroundings. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

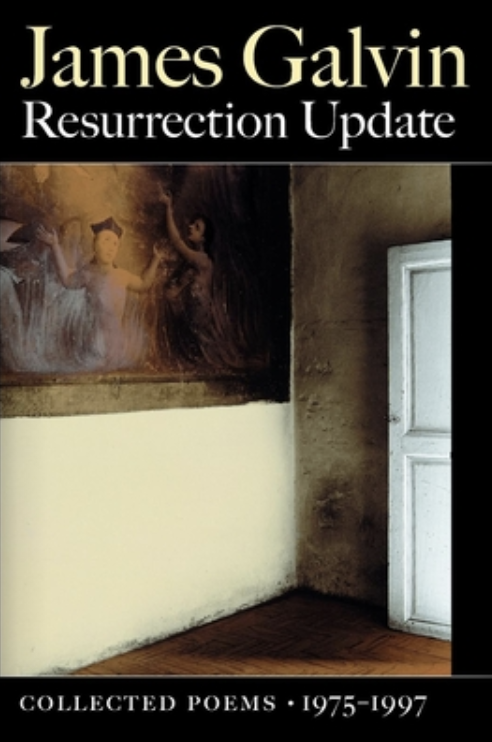

James Galvin, Resurrection Update (1997)

The last few years haven’t been great. Between the ambient alarm of cascading climate crises, the malign discord of incipient fascism, and the ever-present thrum of pandemic anxiety, life for most of us has gotten harder. Which is why so many have turned to poetry in whatever form it can be found. For me, that’s a slow, companionable reread of America’s great existentialist pastoralist, James Galvin. Though I love his lone novel, The Meadow, it’s Galvin’s poetry that has gotten me through the long, high winter of HOW WE LIVE NOW. It is not easy to balance lyricism and realism, but in this collection, spanning over 20 years, one is brought short again and again by the stark clarity of image and idea both.

There are ways of finding things, like stumbling on them.

Or knowing what you’re looking for.

A miss is as good as a mile.

There are ways to put the mind at ease, like dying,

But first you have to find a place to lie down.

–Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Toni Morrison, Sula (1973)

Every bit as brilliant and devastating and darkly funny as I’d been led to believe, Sula (which had been sitting on my bookshelf, unread, for more years than I care to admit) has, I think, overtaken Beloved as my favorite work by the late Nobel laureate. Published in 1973, Morrison’s slim, gothic sophomore novel—a story of intense friendship and seismic rupture, motherhood and sexual freedom, buried trauma and unforgivable betrayal, set in the black neighborhood of a small Ohio town in the 1920s and 30s—is a marvel. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor-in-Chief

Barbara Pym, Excellent Women (1952)

Brought to my attention by the Lit Century podcast, Barbara Pym’s comedy of manners stars 30-something spinster Mildred Lathbury in 1950s post-war London, and let me tell you, Mildred is queen of the silent burn. I wouldn’t call her scathing—she’s far too pious for that—but she notices things. She notices that her two new housemates, a young couple who seem mismatched, aren’t buying any toilet paper for the communal bathroom (“The burden of keeping three people in toilet paper seemed to me rather a heavy one”); she notices when her dinner companions are sloppy eaters (“Surely many a romance must have been nipped in the bud by sitting opposite somebody eating spaghetti?”); she notices that when men refer to her as an “excellent woman,” it’s something of an insult (“Virtue is an excellent thing and we should all strive after it, but it can sometimes be a little depressing”).

There’s no use describing the plot as it’s really Mildred’s voice that carries the novel. Indeed, one gets the feeling that Mildred might be a stand-in for the (unmarried) author herself. Thinks Mildred, “My thoughts went round and round and it occurred to me that if I ever wrote a novel it would be of the ‘stream of consciousness’ type and deal with an hour in the life of a woman at the sink.” Would read! Sorta did. –Eliza Smith, Special Projects Editor

Kazuo Ishiguro, The Remains of the Day (1989)

At the start of this year I decided I was going to listen to audiobooks. Not just “an” audiobook, but to dive right in and become a full on audiobook devotee. I listen to audiobooks when I’m running, when I’m doing the laundry, when I’m walking the dog, while I’m at my kids’ soccer practice and have to “watch” them (they’re little, it’s not so much playing as chasing a ball). And let me tell you, I’ve “read” twice as many books this year as I did last year. I’ve found that I especially like to audio-reread books that I first read years ago, which led me to listen to Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day over five days of running at the beach this summer.

And yes, the story of lifelong butler Stevens recalling his service at Darlington Hall in post-WWI England as he motors to meet Miss Kenton in post-WWII Oxford is strange Jersey-shore reading. But since The Remains of the Day is a perfect novel, it is readable anywhere. Stevens is the best unreliable narrator, so clear in his memories and beliefs and yet so blind to their results. I love the way Ishiguro moves in between the present and the past, and how the past can double on itself. This time, I felt so much more pity for Stevens than I did a decade ago on my first reading, when I thought the most interesting facet of the novel was the idea of England’s national identity. Now it’s the love story that appealed to me most—the lack, the loss. Poor Mr. Stevens! –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Werner Herzog, Of Walking In Ice (1980, trans. by Martje Herzog and Alan Greenberg)

I love Werner Herzog’s slightly unhinged diary of his journey on foot from Munich to Paris to “save” the life of Lotte Eisner. It was early winter 1974 and Herzog, 32 at the time, believed that if he could just suffer the three-week trek it would somehow keep Eisner—his dear friend and fellow filmmaker—from succumbing to grave illness. She was 78 at the time and… guess what? She lived another nine years. Herzog’s account shifts between the observational (“Many, many ravens flying south. The cattle keep stamping during transport, they are restless.”), the meditative (“The loneliness is deeper than usual today. I am developing a dialogical rapport with myself.”), and the mundane (“my left thigh has an ache in it up to my groin”). Through it all, though, Herzog is good company, and reminds us of what it means to make grand—possibly useless, possibly magical—gestures. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

Tara Isabella Burton, Social Creature (2018)

I’m not sure if I can recommend this book, because at some point you will finish it, and then you’ll spend at least the next year searching for another exactly like it. Still, if you’re willing to take that chance, you’ll be rewarded with the perfect literary thriller for New York literary society looky-loos (and really, for anyone who loves impeccable plotting and taut, brutal prose). While the echoes of Tom Ripley are clear throughout the book, Social Creature stands on its own as a dark, nail-biting, and at times hilarious story of wealth, ambition, envy, and of course, literary magazines. –Jessie Gaynor, Senior Editor

Tove Jansson, Fair Play (1989)

Some books come along exactly when you need them; Fair Play arrived in my life this spring, its unassuming story filled with profound assertions about love, art, and partnership between women. Tove Jansson, mainly known for her prolific work in children’s literature, also authored a number of books for adults, including Fair Play, which she published in her mid-seventies (and which was reissued by NYRB in 2007, translated from the Swedish by Thomas Teal). By then, she had been partnered with the graphic artist Tuulikki Pietila for decades; the two women lived together between homes in Helsinki and the tiny Finnish island of Klovharun, their time there punctuated by adventures around the world.

The parallels, here, are clear: Fair Play follows the relationship between Mari, a writer and illustrator, and Jonna, a visual artist, as they live and work on a small Finnish island (and travel). There is no tense build-up here, no pent-up secrets or dramatic conflict. What drives the narrative is the more ordinary, thrumming question that so many of us encounter: how do all the strung-together moments of a life become something meaningful? This story is a quiet delight; I hope it finds you, too, if and when you need it. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Tessa Hadley, Late in the Day (2019)

Generally considered Tessa Hadley’s best novel, I know I am not alone in loving Late in the Day the way I do. A perfect domestic novel, written in spare, pure language, telling you exactly what you need to know—nothing more, nothing overwrought, nothing dramatic in the conveyance. It’s the dichotomy between the huge, revelatory, plotty events that are occurring, and the way it is told, that makes it all the more strained and intense, the pain pushing at the limits of what can be said in simple prose. It’s a story of marriage, not just of the two couples, Christine and Alex, and Lydia and Zachary, but the marriage of the couples to each other. Christine and Lydia, Alex and Zachary, Christine and Zach, Alex and Lydia: the combinations within, and the entity as a whole, something that works best, or maybe works at all, with all four of them.

But immediately the foursome is shattered by the death of Zachary. It’s a loss of a husband and a friend, but it’s also the loss of what these couples could be to each other. Until he died, they didn’t realize what a delicate balance they were all hanging in, perfectly evened out, just the correct amount of close and separate for the marriages and friendships and group as a whole to keep going, keep loving each other. In the wake of his death, in the midst of her grief, Lydia moves in with Alex and Christine. The balances are upset, they are all unmoored in their positions to one another: something unforgivable occurs. What’s even worse than the fact of what happens, is how human it all is, how predictable even. Both human and surreal, lovely, and devastating, it’s everything I could hope a novel to be. –Julia Hass, Contributing Editor

Aimee Bender, The Color Master (2013)

Aimee Bender is a wizard of language. I don’t know how she manages to compress so many big, blobby feelings into such perfect pages. She’s a master of distillation, I guess, is what I mean. If I had one wish, it would be to sit inside her brain and see how she comes up with these things. As per usual, The Color Master is off-kilter and fable-like in the best ways. In one story, a college student ends up at an old man’s house in the middle of the night and discovers some eerie coincidences between herself and his estranged daughter; in another, a person finds that they are losing their vocabulary. In the titular story, a renowned village clothing shop is tasked with replicating the sheen of the natural world in their designs: shoes the color of rocks, a dress the color of the moon. (This one blew my freaking mind.) Every conceit feels so fresh; every sentence slices cleanly. As a writer, she’s obsessed with evolution; at every turn, she is asking smartly: how did we get here? Honestly, I put off finishing this collection for days and days because after this, I knew I was done with her oeuvre. Aimee Bender, on the off-chance that you are reading these, please! I am hungry for more. –KY

Don DeLillo, White Noise (1985)

Nobody told me that this novel was so damn funny, and tender, and existentially terrifying (ok, plenty of people told me that it was existentially terrifying). Now, I know what you’re thinking: he only read White Noise this year because the movie is coming out. First of all, shut up; you don’t know my life. And secondly, so what? I liked Libra. I liked The Body Artist. I was going to get to White Noise eventually. The trailer for Noah Baumbauch’s adaptation just gave me a little nudge. So, thank you, Noah. Even though I don’t particularly care for your films, I’m grateful that you brought Jack Gladney, his crippling fear of death, his unconventional (and often wildly ill-informed) family unit, his libidinous and endlessly-theorizing colleague, and his tin ear for German, into my life. –DS

Joan Didion, The Year of Magical Thinking (2005)

When Joan Didion died late last year, I decided I would reread her novels, memoirs, and essays. The Year of Magical Thinking might be her very best. In it, Didion recounts her experiences of grief after the death of her husband John Dunne. She remembers the night he died, the vacations they took, the deadlines they faced together; she recounts and analyzes his novels and hers, and describes the angst of telling her daughter Quintana, who is hospitalized with pneumonia, about his death. Didion writes with the clarity we all crave when trying to understand our own lives, and sheds light on the way we feel and the people we want to be when faced with tragedy. –EF

Louise Erdrich, Future Home of the Living God (2017)

Louise Erdrich’s 2017 novel cropped up on several post-Roe reading lists this year, and rightly so: not only is there an abortion on the first page, but the story revolves around the policing of women’s bodies as evolution kicks into reverse, throwing the future of humanity (and Earth itself) into question. Our narrator is pregnant 26-year-old Cedar Hawk Songmaker, an Ojibwe adoptee who grew up with liberal white parents in Minneapolis. Scared, alone, and on a frightening Most Wanted list of sorts, Cedar seeks refuge with her biological family and keeps a record of her life in notebook entries addressed to her unborn son. In the background, signs of the end times (or the beginning times?) emerge: ancient species reappear, fundamentalist religions take hold, reproductive bodies are forced to reproduce. At the same time, Cedar’s Ojibwe tribe regains its land, and her depressive stepfather finds hope in their people’s continued evolution. Erdrich writes along the tight rope of optimism and despair in this tense, pensive novel that often feels like a thriller. –ES

Muriel Spark, The Girls of Slender Means (1963)

I believe everything about this book is perfect, starting with its title. Muriel Spark’s (slender) novel, set in just-postwar London (“when all the nice people in England were poor, allowing for exceptions”), follows of the inhabitants of the May of Teck Club, a residence hall established “for the Pecuniary Convenience and Social Protection of Ladies of Slender Means.” The novel, which moves easily among the young women’s stories, is a masterclass in polyphony, and a mind-boggling combination of savage humor and lightly obscured (for a while, at least) tragedy. It’s also one of the most economical and precise books I’ve ever read—every detail is the correct one, and not a word is out of place. I suspect this one will be on my re-read list for years to come. –JG

Izumi Suzuki, Terminal Boredom (2021)

Published last year by Verso Books, Terminal Boredom gathers seven stories by Japanese countercultural legend Izumi Suzuki, translated by Polly Barton, Sam Bett, David Boyd, Daniel Joseph, Aiko Masubuchi, and Helen O’Horan. In spite of all the truly good science fiction out there, it isn’t normally my thing; Suzuki blasted through any hesitation I had with this blunt, restless collection. Don’t take anything for granted in a Suzuki story; the worlds she creates are absurd, her narrators alternately testing the social constrictions of their respective worlds and worn out by the impossibility of resisting authority. Verso also announced last year that it will publish Love < Death, another Suzuki collection, at some point in the future, for which I’m already excited. –CS

Miriam Toews, Irma Voth (2011)

I’m a Miriam Toews completist, or at least an aspirational one, just to give a sense for why I’m perpetually recommending her. While not my absolute favorite of Toews’ novels, her writing is so consistently faultless, that even her worst work (not that this is that!!) would be better than most things I read. From 2011, it reads as still working up to her greater novels (All My Puny Sorrows, Fight Night), though still rife with typical Toews-isms. It centers around a Mennonite community, and a plucky, funny female protagonist who can’t quite live the way her devout and terrifying father wishes her to. She’s managed to escape, in a sense, through her marriage to Jorge, yet he too ends up wanting something from her that she can’t give.

The rigidity of the roles in a Menonnite community are so completely at odds with the full, messy, spark-plug characters running through all of Toews’ novels. These characters have a life-force that pushes them out and away from the community they were born into, and yet they still wish to belong, still wish for family, unconditional love, still wish to understand their place in the world. It’s a dramatization of how any human feels, trying to learn how to live, but Irma Voth is having to build it all from the ground up. The writing mirrors the process: rushed, urgent, hilarious, confused, halted by grief and failure, and yet kept afloat, kept joyful, by light and jokes and sisters and hope. –JH

Ruth Ozeki, The Book of Form and Emptiness (2021)

Ruth Ozeki’s wildly inventive novel is like nothing I have ever read before. This is the story of Benny Oh, who starts to hear voices after his father’s tragic death. For Benny, the voices have a clear source: they are the objects around him speaking to him. Some of them have a chipper tone, but others come across as much more sinister. As his grieving mother becomes a hoarder, Benny can’t seem to find peace in his home; the voices are too loud. He finds sanctuary at the public library, where everything is a whisper. (This is a real book lover’s book.) At the library, he also meets a beautifully strange cast of characters—and his own Book, who talks to him, guides him, and helps him learn to tell his own story.

What’s really spectacular about this book is Ruth Ozeki’s ability to walk the line of mental illness and magical realism. (An early line: “Music or madness. It’s totally up to you.”) Of course, in a way, this is a story of a mourning family and the mental health problems that intense loss triggers. This is not glossed over; there are sections that take place in a psychologist’s office and in a mental health facility. But it’s a story that also meets the characters where they are and takes their lived realities seriously. There are whole swaths of the novel that are told from the perspective of Ben’s Book; we hear what he hears. The world Ruth Ozeki has created here is laced with magic. –KY

Art Spiegelman, Maus (1991)

Beautiful and horrific, a rendering in miniatures of the most monumental and incomprehensible of horrors, I couldn’t tear my eyes away from Art Spiegelman’s masterwork—its crowded expressionist panels spilling over with brutality and humanity, its tender but unsparing framing narrative, it’s refusal to deify its heroic, haunted protagonist—which, I was pleased to discover, was not banned and/or removed from my local library here in Wyoming. Heralded as a genre-definer for a reason. –DS

Simone de Beauvoir, tr. Sandra Smith, Inseparable (2020)

The moment I started this book, I felt as if I were back in Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels: two precocious young girls, the narrator not just admiring of but entirely enamored by the other. It feels authentic partly because it is: the novel is based on de Beauvoir’s pivotal relationship with her best friend, Élisabeth “Zaza” Lacoin, who died at the age of 22—“murder[ed] by her environment, her milieu,” de Beauvoir later wrote in All Said and Done, Zaza’s milieu being the bourgeoisie and organized religion, both punishing and repressive of her natural zeal for life. Originally written in 1954 and deemed by its author “too intimate” to publish, Inseparable is moving and distressing, infuriating in its incompleteness, and a must-read for de Beauvoir and Ferrante fans alike. –ES

Joanna Faber and Julie King, How to Talk So Little Kids Will Listen (2017)

We often turn to books as an alternative to shrieking into the void, but when you’re the parent of a toddler, you also need them when the void is shrieking into you. (In this case, yes, the void is the toddler. I love my precious void. I’m very tired.) Perhaps the most helpful book I read this year, in a purely pragmatic sense, was How to Talk So Little Kids Will Listen, which offers legible advice on exactly what its title promises. While it might not offer the electric prose or masterful world-building (just guessing) of some of the other titles on this list, if you have a young child who screams like they’re auditioning for Jason Blum through every. Single. Car ride, I can’t recommend this one highly enough. (Regarding the car, ours is now equipped with an ice cream button, a pretzel button, an Elsa and Olaf button, and a nice dinosaur button, all of which we encourage our kid to press whenever she’s feeling the need to shriek. Amazingly, this actually works.) –JG

Rachel Carson, Under the Sea-Wind (1941)

Rachel Carson’s first book, Under the Sea-Wind, which grew from her work as a writer for the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, brings together the stories of the ocean’s inhabitants in a pluralistic celebration of its beauty and complexity. Spending any amount of time with this book feels like standing at the water’s edge with Carson as a patient guide; it is a beautiful work of deep observation, an informative look at the ecology of ocean habitats, and an amazing achievement of environmental writing. Spending time with it this year felt like taking an antidote to everything that feels overwhelming in the world. –CS

Beth Morgan, A Touch of Jen (2021)

A Touch of Jen is so bonkers and unhinged it’s hard to even know fully what to say about it. It’s a tale of obsession, social media, desire, and the void at the center of our fixations on aesthetic, and other people’s lives. If you’re like me, you might be immediately tired by descriptions lauding a book for tackling our social media age and internet culture. Kind of like how books about Trump or the pandemic can sound god-awful: we can’t escape it in life! Why would I read about it too? All to say, it’s a high compliment when a book manages to center itself in the internet universe and still pierce through the immediate wariness. It’s ludicrous, extremely discerning, and totally bizarre: you’ll just have to read it to know what I mean. –JH