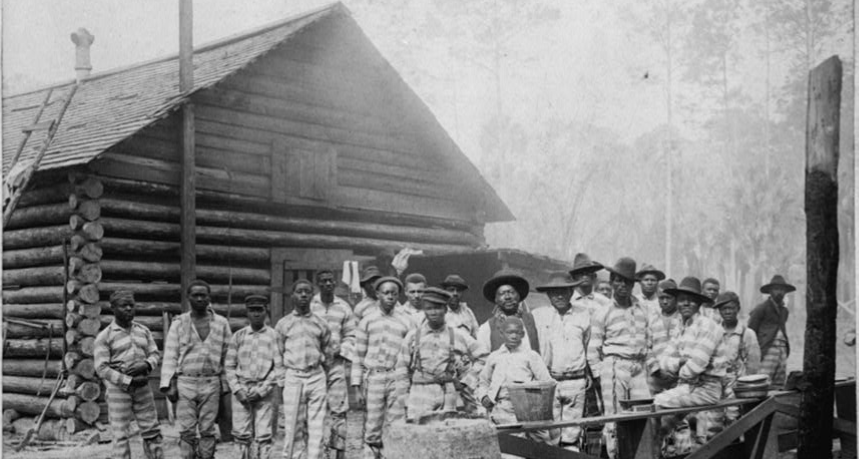

Prisoners stumbled and clanked through the predawn light, making their way from the stockades where they slept to the mines where they labored in darkness. Prodded by guards and hobbled by ankle irons, they trudged every morning but Sundays through the heat, the rain, and even the occasional Alabama snow. Upon arriving at the pits, they descended into the miles of underground blackness that laced the earth just outside Birmingham.

Armed men stood watch over the entrances for the duration of their labors as the prisoners mined coal. They drilled holes for explosives, ignited them, and released avalanches of rock, which they then sorted and loaded by hand. Often on their knees, sometimes in water up to their chests, each convict dug and moved eight to twelve thousand pounds of slate and coal per day over the course of their sentences. Fueled by meager rations, they managed to pile incredible tonnage into coal cars to be pulled up to the daylight by mules.

The convict lease system is starkly emblematic of the terror that filled the void left by the retreat of federal authority. After the collapse of Reconstruction in 1874, convict leasing took off rapidly to become a system of labor, a mode of social control, a shortcut to industrialization, and a stream of private and political revenue—a panacea, really, for all that ailed white Alabama in the last quarter of the nineteenth century.

The African American prisoners hailed mostly from the Black Belt, convicted of a variety of crimes—some small, a few real, most trumped up. Labor contractors bought up their sentences and fines from county jails and the state prison and then leased them to the mine operators at a tidy profit. The prisoners had no choice but to sign the contract placed in front of them by the labor contractors.

Although the prison miners, unlike chattel slaves, had hopes of regaining their freedom one day, unlike with slavery their overseers had no investment in keeping them healthy or even alive. Convicts were disposable, cheap, and in near infinite supply. The convict labor system reestablished the terms of the old regime but looked to the future, balancing the slavery past and the industrial future.

Convict leasing, as well as other horrors such as lynching and constitutional disenfranchisement, flourished in the void left by the retreat of federal power after the 1870s.

The prisoners resurfaced after dark and dragged themselves back to the stockade in their leg irons. For months they did not shower and changed clothes only rarely. The convicts ate their meager grub and lay their bodies down on vermin-infested bedding packed into windowless rooms and surrounded by overflowing buckets of human waste filled by men not infrequently dying of dysentery. The only fresh air available filtered through the slim cracks in the walls.

One state official described the “damp sleeping clothes, damp bedding, deficient cubic space and ventilation, want of sunlight in the cells, and, for the men, cold water for bathing purposes, and general overcrowding.” It was “unfit in every particular for the habitation of animal beings.” The threat of the lash, a heinous symbol of the slave system, returned. According to one report, every single miner had either been whipped or witnessed a whipping. Even the most basic health care was lacking, and many were maimed in the various tortures designed to enforce discipline.

Convict leasing, as well as other horrors such as lynching and constitutional disenfranchisement, flourished in the void left by the retreat of federal power after the 1870s. Whereas the Black vote and the Republican Party—and the federal authorities that assisted them—all lost political legitimacy, the locking up of prisoners to use as convict miners had the full sanction of the county, the state, and much of the region.

The stunning thing about convict leasing was the rapidity with which it grew after the coup of 1874, during which a mob of White League Democrats in Eufaula, Alabama massacred Black Republican voters at the polls. Back when African American “crime” had been the responsibility of masters and plantation managers, Black people represented zero percent of the prison population. As Reconstruction collapsed, however, the Black conviction rate rapidly rose. African Americans made up 8 percent of the total convict population in 1871, leaping to 88 percent in 1874, and then 91 percent in 1877. And the mines boomed.

The state commissioner of industrial resources noted that mining was in the “merest dawn of its infancy,” with just 40,000 tons mined in 1873. Just over ten years later, the state mined 2.2 million tons of coal, of which 401,000 tons were mined by prisoners. When Tennessee Coal and Iron, typically known simply as TCI, came to town, they consolidated “the largest coal company in the South.” Half of TCI’s output was dug by prisoners. In 1886, the firm alone contracted for six hundred miners for ten years.

One convict who did time in the horrors of both the Eureka and Pratt Mines had the audacity to write to the reform-oriented prison inspector about conditions. “Have worked hungry thirsty,” Ezekiel Archey complained, “half clothed & Sore.” Sentenced to ten years for burglary and larceny, crimes which he may or may not have committed, he managed to survive long enough to be released—though they kept him longer than his original ten-year sentence. “All These years oh how we Sufered. No Humane being can tell.” Throughout Ezekiel Archey’s sentence, death haunted him. “Some one of us. were carried to our last Resting. The grave. Day after Day we looked Death in The face & was afraid to speak.”

After grueling days of digging coal, their cells filled with filth and disease and the stink of human waste, he said. They went to bed wet and woke up wet: “our Agony & pain seams to have no End.” Even in the stockade, where he slept, ankles chained to the bed, the smell of excrement in the air, they still had to listen to “Every Guard Knocking beating yelling.” He concluded: “Fate Seems To curse a convict Death Seems To Summon us hence.” The convict mines were located far from Barbour County, some 180 miles northwest of Eufaula, in the north-central part of the state near Birmingham. Many convicts, however, were from Barbour County. Ezekiel Archey was not. But one of the primary individuals who masterminded the convict lease system and profited from Archey’s fate and that of hundreds of other prison miners was one of Barbour County’s most prosperous and powerful citizens, J.W. Comer.

The Comers were among the county’s most prosperous families and owned one of the biggest plantations up at Spring Hill, the location of the shooting of Judge Keils’s son. Comer was, as one Republican put it, “the head and front of that Spring Hill mob” that ambushed the polling station in 1874. He tried to bribe Judge Keils prior to the destruction of the ballot box and the shooting of Willie Keils.

Having fought in the Civil War and done all he could as a local Barbour County “hero,” as they called him for his efforts to undermine Reconstruction, J.W. Comer had found his way to a bold and profitable business. With the void in federal and Republican power after 1874, he could pay the county jails and state penitentiary for their prisoners and then lease them to the mines. From his remote corner of southeastern Alabama, and later, from the mines themselves, he became a kingpin in a complex interlocking system of convict leasing. Funneling free people into jail, and then convicted African American men into the mines, Comer helped create some of the most brutal labor conditions ever devised on “free” American soil. Along the way, the system fed the empty state coffers and enriched J.W. Comer.

Local prison logbooks are filled with mysteries. Most convicts were young men, some were old, a few were women. Their sentences ranged from a single year to the rest of their lives. Their crimes allegedly included everything from murder to arson to gambling to burglary to “not stated.” J.W. Comer owned the contract on one Barbour County local, John Baxter, for instance, who, at the tender age of thirteen, had been taken into custody on November 22, 1878, for the crime of “aiding prisoner to escape.”

Perhaps he was trying to liberate a father or brother from the convict mines, but we’ll never know. His sentence was two years, and Comer leased him into the mines. Another fifteen-year-old boy from Barbour County, Mose Granville, got five years for “grand larceny.” They listed his conduct in the mine as “bad.” Ned Jones was contracted to Comer for four years for “adultery,” perhaps suggestive of the obsession with using sex to reinforce the race line. They got Jim Morris for “grand larceny.” Comer paid top price, $18 per year, for one Henry Caruthers, who was enslaved to him for five years; Spencer Caruthers, probably his brother, got two years.

Whether the two young men were engaged in some criminal enterprise or whether some white man wanted their family land and needed them gone, we’ll never know. In Barbour County, almost seven hundred convicts were leased out just between 1891 and 1903 alone. Most of them were destined for one of two big Birmingham firms, either Tennessee Coal and Iron or Sloss-Sheffield Steel and Iron. The going rate for leasing out was about $6 per month.

The reinstatement of slavery-like conditions required only the excuse of a crime in need of punishment.

No matter how they got into the mines, prisoners had a way of getting lost in the system. As the state board of prisons complained of the county system in 1886, there was not “anything like a record kept until a few years ago and we have had application made to us to ascertain what has become of persons sentenced to hard labor prior to 1883, of whom there is absolutely no trace; they have disappeared as completely as if the earth had opened and swallowed them.” The earth had, indeed, swallowed them, lost as they were in some mine tunnel someplace, remembered only “by the few at the humble home, who still wait and look in vain for him who does not come.”

Officials advertised their prisoners or received solicitations from private lease operators like Comer, who had men posted at the county courts to take advantage of the policies on court costs. County convicts faced responsibility for their own court costs, sheriff fees, jurors’ fees, and costs of trial, which Comer’s men paid off and then took the prisoners into indentured servitude. Later they would be charged for food, medical treatment, and upkeep, which amounted to even more substantial and unpayable costs. Under the lease system, the convicts could then work off their growing debt by adding additional time onto the sentence they received for their alleged crimes. Misdemeanors in the Black Belt were translated into significant profits.

The county convicts often functioned free of the limited regulatory oversight of the state, and this created substantial financial incentive to increase the number of local prisoners in the system. For the county, it was not just the chance to outsource the care and feeding of prisoners, it was a chance to make real revenues in lease fees. Draconian laws served economic as well as political power. They were designed, claimed one critic, “to place the liberty and equal rights of the poor man, and especially of the poor colored man, who is generally a republican in politics, in the power and control of the dominant race, who are, with few exceptions, the landholders, and democratic in politics.”

Republican critics recognized that incarceration and convict leasing provided means not just of generating profits but of reestablishing antebellum race and labor relations. “The accused is little better than a slave,” explained the Republicans remaining in the General Assembly of Alabama about the changes to the state penal code. “We need not remind you how such a policy [of convict leasing] is at variance with all the results intended to be wrought out by the war for the preservation of the Union.

That was a conflict of ideas as well as of armies,” the report argued, “while the slave-labor system did not triumph at Appomattox, they are thus seen to be practically triumphant in Alabama.” Should such a convict regime prove successful and durable, they continued, “it would practically reverse the verdict wrought out at the point of the bayonet, reverse the policy of reconstruction, and strike out of existence not only our free-State constitutions, but the laws made in pursuance thereof, thus violating the fundamental conditions of the admission of Alabama into the Union. If this is allowed to be done, it is not difficult to perceive that the war for the Union was a grand mistake, and the blood and treasure of the people spent in vain.”

The Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery. The amendment contained a complicated clause, however, that allowed for considerable maneuvering. Slavery would no longer exist “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” This became known as the “exception clause.” While the clause lends readily to a sense of conspiracy, its language had been in use for decades in a variety of statutes that banned slavery. Northern prisons included labor, and few believed they should be emptied out.

Still, alternatives had been presented at the time. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts and Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, the lions of Radical Republicanism, believed that the difference between race slavery and the penal system required more clear and aggressive separation. Republicans tried to make clear that this was not supposed to encourage convict leasing or for-profit penal systems. Their ideas were not adopted. Instead, the reinstatement of slavery-like conditions required only the excuse of a crime in need of punishment.

________________________________

Excerpted from Freedom’s Dominion: A Saga of White Resistance to Federal Power, by Jefferson Cowie. Copyright © 2022. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.