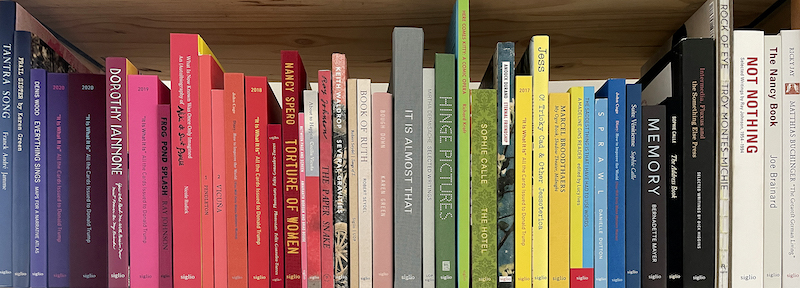

Featured image from Sophie Calle’s The Hotel.

The Siglio origin story famously begins with founder Lisa Pearson in Prague in the days before with Velvet Revolution being slipped a samizdat copy of exiled novelist Milan Kundera’s incendiary novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Which is to say, in commission of a crime. Because anyone found in possession of the manuscript could be arrested. The novel, a re-typed typewritten translation of a contraband English edition has been mimeographed on cheap paper, so it appears, as Pearson recalls, “as subversive as a thick stack of Communist-era restaurant menus.”

The moment Pearson passed Kundera’s novel-in-disguise to the next person at great risk to her and the next reader, she became a publisher. It’s not surprising that she’d find her calling publishing books whose deeper meaning is revealed in the marriage of the book’s physical form and literary content. Hybrids of art and text that don’t respect boundaries but deal in the frisson created when collage cross-pollinates with fiction, poetry speaks through photographs, graphics accesses emotion the memoir can’t, and paintings remember what history forgets. This unique form of reader engagement is what Siglio books trade in, and it’s what turns readers like me into brazen proselytizers pushing Siglio books into the hands of friends and strangers like a love-drunk publicist.

Which is a very good thing because it isn’t as if Pearson has a large advertising or publicity department—no, Pearson is a one-woman show. Not only the founder and publisher of Siglio but also editor-in-chief, editor, copy-editor, art director, and the person who gets the coffee.

It’s been this way since Pearson started the company fourteen years ago in Los Angeles. Today located in New York’s Hudson Valley, Siglio publishes out of a converted barn that looks over rolling green hills. To date Siglio has published forty books including dozens of artist and ephemera editions.

“The reason I can do Siglio is because I am good at spreadsheets and managing my meager resources and good at getting my distributor enthusiastic about my books,” Pearson says. But it comes with a price. One can imagine Pearson stopping just short of poring over nautical maps tracking the ship transporting copies of poet-photographer Bernadette Myer’s Memory.

“I don’t think I’m unique. I think anybody who starts a small press is the same—I really do—if you start a small press—you know, Why? Why would you do that?”

Given the pandemic it is remarkable, although not shocking to those who know Pearson, that Siglio was able to publish What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined: An (Auto)biography of Niki de Saint Phalle by Nicole Rudick in 2021, and most recently in the middle moving the whole operation, Christian Marclay and Steve Beresford’s elegiac Call and Response, a distillation of “seeing music in the quiet of the pandemic: a dialogue between two protagonists of experimental music in photographs and scores.”

*

Siglio books can be a devil to shelve. Will you find artist Richard Kraft’s It is What It Is, a graphic representation in the form of soccer referee’s cards flagging Donald Trump’s flagrant misconduct, with the artistic ephemera, politics, or true crime? Should artist-author Karen Green’s Frail Sister, an excavated scrapbook of a missing woman’s life revealed in drawings, letters, and altered photographs, be displayed with the art books, mystery novels or feminist studies?

You might imagine from the wallpapered cover and gilded pages of Sophie Calle’s latest book from Siglio, The Hotel, that you are holding a slick book of interiors. Only to find when you lift the cover that it’s a provocative, gritty black and white photo-journal of Calle’s undercover turn as a hotel maid. Not a celebration of lobby décor, more evidence from a crime scene gathered for the purpose of unpacking the private lives of unsuspecting guests. It’s disquieting, as it should be. It is one thing to passively receive photographed images, another to actively engage with Calle’s narrative, to allow oneself to be seduced into the role of voyeur and co-conspirator.

It’s not the kind of book the staid publishing behemoths are eager to clasp to their buttoned-up bosoms. (Pearson also published Calle’s critically adored Suite Ventienne and Address Book.) For her, the fact that a book is one that other houses “run screaming from” is a bonus.

“My job is to realize the artist’s vision in the shape of a book and then cultivate an audience for it.”

“If I can think of two or three other presses who would be really into this, and love this, it’s not a Siglio book. If someone else is interested, by all means go with it, because I’m not in competition with anybody, and if that’s a good home for your work that’s great.”

Pearson’s pro-art, pro-author point of view is the antithesis of that shared by most mainstream publishers. Her job, she says, is “to realize the artist’s vision in the shape of a book and then cultivate an audience for it.” It’s enough to make an author weep.

*

Historically, white men, by virtue of gender and a slap on the back, have been the only ones with the means and audacity to launch such publishing endeavors. Having cut my teeth as a young editor working for George Plimpton at The Paris Review, I know Pearson is a unicorn.

She disagrees. “I don’t think I’m unique. I think anybody who starts a small press is the same—I really do—if you start a small press—you know, Why? Why would you do that?”

Even so, I say, surely someone had to have given her permission.

“No one,” she laughs. “It was hubris. Stupidity.”

That said, Pearson is quick to cite the enormous influence avant-garde artist Dick Higgins has had in shaping her world view. “He is a totemic presence for me in this idea of taking the mechanism of offset printing and trade publishing and utilizing them in this service of the avant-garde—to get that work into unsuspecting hands and to disseminate it widely.”

It is in this spirit of rebellion and upsetting capitalistic narratives that Pearson began putting together a free “newsletter” in pre-pandemic 2020, fittingly named, “The Improbable.” Characterizing it as a “newsletter” is deceiving as it’s no throwaway, but a miscellany of ephemera from many of the same writers, artists, thinkers, and mischief-makers already in the Siglio orbit.

The first Issue No. 1 (Time Indefinite) was followed last year by Issue No. 2 (Time is Elastic). Issue No. 3 is glimmering on the horizon of early 2023. She conceived of the idea she says with barely suppressed glee, “without any ambitions to reach any particular reader or demographic: the opposite, I hoped, of commerce. It is meant as an unexpected gift.”

The concept of a publisher giving away anything, save for a tote bag, for free, is improbable. It’s radical. I can’t help but see this as a challenge to the publishing industry to become less merchants of books and more agents of curiosity and ideas. Stop policing the imagination. Think less about how to homogenize and convert the writer’s vision into an easily digestible product and spend more energy exploring transformative experiences readers yearn for.