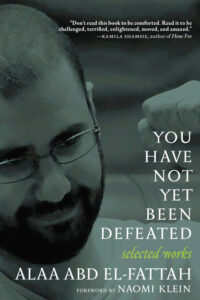

You Have Not Yet Been Defeated, a collection from Alaa Abd el-Fattah published this year by Seven Stories Press, is living history. Many of its words were first written with pencil and paper in a cell in Egypt’s notorious Torah Prison, and smuggled out in ways we likely will never understand. One was drafted in collaboration with another political prisoner, the two men shouting ideas to each other across the dark ward. A few texts were written in relative freedom, on the eve of repeated imprisonments, or during probationary release, in an isolation cell at a police station where the author was required to spend his nights.

At every stage, and whichever form they take—essay, letter, interview, tweet, speech—they exist only because of extraordinary risks taken by the writer, intellectual, technologist and Egyptian revolutionary Alaa Abd el-Fattah. Those risks include the ever-present threat that Alaa would face further ludicrous charges, and prolonged detention. In the case of texts written during stints on the outside, or during probation, the threat—made explicit in night-time visits from state security officers—was that these writings would lead directly to his re-imprisonment, or worse. And still, he wrote.

The fact that these words can be published now, in book form, many for the first time in translation, is a result of further risks, these ones taken by friends, family, and comrades in Egypt’s luminous but brutally extinguished revolution. The ones who camped outside the prison to demand communication with the prisoner; who smuggled out hidden slips of paper; who selected the texts from Alaa’s huge body of work; who edited, translated, and contextualized them in these pages.

Alaa acts as the revolution’s toughest critic and its most devoted militant.

This careful work has taken place against the backdrop of continuous and escalating state repression against the regime’s political opponents. That opposition is politically and ideo- logically diverse. Alaa and his comrades are part of the left, internationalist, anti-sectarian, youth-led movement that is part of a global confrontation with transnational capital and its national organs, a movement that has seen expressions from Tahrir Square to Occupy Wall Street. And because this strain has refused to fully surrender its hopes for a liberated Egypt, it too has faced the wrath of the vengeful regime of General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi.

As I write, Alaa is re-imprisoned, as he feared he would be, and the silence from his cell is harrowing. His sister, Sanaa Seif, a prominent organizer in her own right, is also in jail, most recently for “spreading false news.” His editors at Mada Masr, where many of Alaa’s writings first appeared, have also faced harassment and detention for their commitment to independent thought in a sea of state propaganda.

Alaa, as you will read, is a student of the South African freedom struggle, and in particular the Freedom Charter—a document that laid out a roadmap for collective freedom written under one of the most repressive periods of Apartheid rule; a document whose meaning and import were magnified by the raw difficulty of bringing the text into being. This text is also a product of revolutionary effort, of subterfuge and hope. In the age of “frictionless” everything, it is born of pure friction.

All of this makes the book’s very existence remarkable—and yet none of this friction is why it must be read. It must be read for the precision of its language, for its bold experimentations with form and style, and for the endlessly original ways its author finds to express disdain for tyrants, liars and cowards. Most of all, it must be read for what Alaa has to tell us about revolutions—why most fail, what it feels like when they do, and, perhaps, how they might still succeed. It is an analysis rooted as much in a keen understanding of popular culture, digital technology, and collective emotion as it is in experiences confronting tanks and consoling the families of martyrs.

Most of all, it must be read for what Alaa has to tell us about revolutions—why most fail, what it feels like when they do, and, perhaps, how they might still succeed.

So, for instance, in the handful of months when Alaa was on probationary release from prison in 2019, before his reimprisonment, he shared several reflections on how the outside world had altered during his years of incarceration. When, he wondered, did otherwise serious adults start communicating with one another via emojis and gifs? Why, amidst the constant online chatter, was there so little actual discourse—engaged people building on each other’s knowledge of history and current events to create shared meaning?

In an interview with journalists at Mada Masr, Alaa observed that, “Getting out [of jail], I feel like we’ve gone back to the Stone Age. People speak in emojis and sounds—ha ha ho ho— not text. Text and the written word are great. So I’m disturbed.” He describes a debate about whether veterans of Tahrir Square have anything to teach youth in Sudan, who were, in 2019, waging a courageous uprising of their own. “And you’re in these circles of people sending gifs and heart emojis . . . This medium is stifling. It’s very strange that the entire world knows that these tools and mediums are defective and they have no faith in them and are suspicious of them, but they just keep using them. There’s a need for an alternate imagination.”

This critique of the ways corporate communication platforms systematically infantilize and trivialize consequential subjects carries particular weight because Alaa is no technophobe. On the contrary, he is a programmer, a world-renowned blogger, as well as a social media aficionado with close to a million followers across platforms. He came to activism as a teen in the late 1990s and 2000s, surfing the liberatory promise of the pre-social media internet, a time when email lists and Indymedia networks were weaving together emergent movements across continents and oceans, converging to show solidarity for Palestine and the Zapatistas; to oppose corporate globalization from Seattle to Genoa to Porto Alegre; and to try to stop the 2003 US-UK invasion and occupation of Iraq. As a worker, the internet was Alaa’s day job; as an activist, it was one of his key weapons.

And yet in his own life, he had watched these networked technologies—filled with so much potential for solidarity, increased understanding, and new forms of internationalism—turn into tools of aggressive surveillance and social control, with Big Tech collaborating with repressive regimes, governments using “kill switches” to black out the internet mid-uprising, and bad-faith actors seizing on out-of-context tweets to slander reputations and make activists markedly easier to imprison. Interestingly, it is not these explicitly repressive applications that most preoccupy Alaa in these pages.

As he wrote in 2017, “My online speech is often used against me in the courts and in smear campaigns, but it isn’t the reason why I am prosecuted; my offline activity is.” This insight may come from being raised in a family of revolutionaries, with his father, the renowned human rights lawyer Ahmed Seif el-Islam, behind bars during Alaa’s early years. He knows well that authoritarian states will always find ways to surveil and entrap the figures that pose a material threat to their hold on power, whether through digital tools or analogue ones.

He had watched these networked technologies—filled with so much potential for solidarity, increased understanding, and new forms of internationalism—turn into tools of aggressive surveillance and social control.

Nor was he under any illusion that Silicon Valley was a partner in his people’s liberation. In one of this book’s most prescient passages, Alaa, writing without Internet access in a prison cell in 2016, predicted the Covid-19 lockdown lifestyle almost to the letter, with its attendant attacks on public education and labor standards. Mimicking the breathless techno-utopian tone, he wrote:

Tomorrow will be a happy day, when Uber replaces drivers with self-driving cars, making the trip to university cheaper; and the day after will be even happier when they abolish the university, so you’re spared the trip and can study at Khan Academy from the comfort of your own home. And the day after will be even happier still when they do away with your trip to work and have you doing piecework from home in a flexible, sharing-based labor market, and the day after will be happier and happier when they send you off for early retirement because you’ve been replaced by a robot.

This kind of analysis of the workings of capital meant that, while others enthused about “Facebook Revolutions” and “Twitter Uprisings,” Alaa was able to remain clear-eyed about who these companies were and whose interests they served. In 2011, in an interregnum before his long prison sentences began, Alaa travelled to California to keynote RightsCon, the inaugural Silicon Valley human rights conference which now takes place every year. The crowd surely expected this hero of Tahrir to flatter them with tales of how their companies had aided in Egypt’s revolution and how they could further advance their mutual goals of democracy and liberation. Instead, as we read in a transcript of that speech, he declared himself “quite cynical” about the gathering’s entire premise. “Sure, it would be nice if the giants of Silicon Valley were dedicated to protecting and advancing human rights, but corporations are not really likely to do any of that.” What they are built to do is

monetize every single transaction . . . I don’t expect either Twitter or Facebook or the mobile companies to change their business models just for activists, so that is not going to happen . . . What needs to happen is a revolution. What needs to happen is a complete change in the order of things, so that we are making these amazing products, and we’re making a living, but we’re not trying to monopolize, and we’re not trying to control the internet, and we’re not trying to control our users, and we’re not complicit with governments.

Over the subsequent decade, events would bear out these insights so thoroughly that it’s easy to forget that in 2011 Silicon Valley, they were close to heresy.

Rather than treating these companies like revolutionary comrades, Alaa chose to discuss the subtler impacts of social media and platform communications on daily life, the quality of discourse, and on the formation of fragile and vulnerable identities.

We leftists have been known to spend years staggering around like golems inside the husks of our movements, unaware that we have been drained of our animating life force.

It’s fitting that Alaa would zero in on regression when he was able to re-engage online after what he described as his “deep freeze.” Fitting because inducing a regressed state in the incarcerated person is the goal of prisons like the one that swallowed him up, as it had his father before him. Isolation, humiliation, continuous changing of the rules, severed connections with the outside world—all of it is designed to achieve a numbed and nullified state of submission. Which makes it all the more remarkable that prison did not succeed in inducing regression in the author, quite the opposite. This book is surely testament to that.

In addition to the dexterity of its prose, as well as the acuity of its ideas, this book is remarkable for its consistent political maturity. Mature because it does something very rare in the canon of movement writing: look squarely at just how much has been lost.

Since becoming part of the alter-globalization movements in the late 1990s, a global network that Alaa joined as a teen, I have been struck by how hard it is, from inside an uprising’s nucleus, to even know when a revolutionary moment has passed. Among core organizers, there are still meetings, still strategy sessions, still hopes for a new opening just around the corner—it’s only the masses of supporters who are mysteriously absent. But because their arrival was always a little mysterious to begin with, that too can feel like a temporary state rather than a more lasting setback. Indeed we leftists have been known to spend years staggering around like golems inside the husks of our movements, unaware that we have been drained of our animating life force.

This text is also a product of revolutionary effort, of subterfuge and hope. In the age of “frictionless” everything, it is born of pure friction.

Alaa speaks to this eerie, undead stage of political organization, writing, with his devastating precision, of a time when “the revolution did not yet believe itself to be over.” Or of the period, in 2013, when the liberatory spirit of Tahrir had been supplanted by a battle between the Muslim Brotherhood and security state: “My words lost any power and yet they continued to pour out of me,” he writes. “I still had a voice, even if only a handful would listen.”

Alaa is no longer on that kind of political autopilot. Instead, he has spent years probing the toughest of questions: Have we actually lost? How close did we get? What can we learn going forward so we stop losing? His assessments in this collection are utterly devoid either of easy boosterism or self-indulgent doomerism. He recognizes the movement’s glories, honors the life-altering “togetherness” of Tahrir Square. And yet, he acknowledges, Egypt’s revolution failed in its most minimal common goals: to secure a government that rotates based on democratic elections and a legal system that protects the integrity of the body from arbitrary detention, military trials, torture, rape, and state massacres.

It also failed, at the peak of its popular power, “to articulate a common dream of what we wanted in Egypt. It’s fine to be defeated,” Alaa writes, “but at least have a story—what we want to achieve together.” Reading his earlier, more programmatic essays, it’s clear that this was not for lack of ideas. Inspired by the extraordinary grassroots process that led to the drafting of South Africa’s Freedom Charter, Alaa had a vision for how the movement that found its wings in Tahrir Square could fan out across the country and engage in “intensive discussions with thousands of citizens” to democratically develop a vision for their collective future. “Since we’ve agreed that the constitution is one of the key goals of our ongoing revolution, why not include the revolutionary masses in its drafting?” Trapped between top-down political parties who wanted no part of this kind of participatory democracy and by street activists who were dismissive of state power, the idea died on the vine.

“But,” Alaa adds to his stark assessments, “the revolution did break a regime.” It defeated much of Mubarak’s machine, and the new junta that is in its place, while even more brutal, is also precarious for the thinness of its domestic support. Openings, he tells us, remain. In this way, Alaa acts as the revolution’s toughest critic and its most devoted militant. Which makes sense, given where he is. This is a writer for whom every outward communication is a risk, and who therefore cannot afford either the delusion of over-inflating his movement’s power or the finality of discounting its latent potential. He has time only for words that hold out the possibility of materially changing the balance of power.

___________________________________

You Have Not Yet Been Defeated by Alaa Abd el-Fattah is available from Seven Stories Press.