Multihyphenates can get a bad rap, accused of not committing to one thing: operating in the gig economy, creators can feel pressure to specialize. But just because many artists are canonized in one discipline doesn’t mean they didn’t work in others. For instance, before Flannery O’Connor—who died this week in 1964—was a writer, she was primarily an aspiring cartoonist.

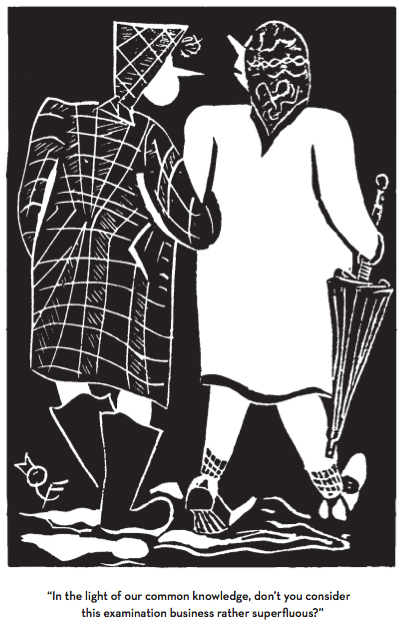

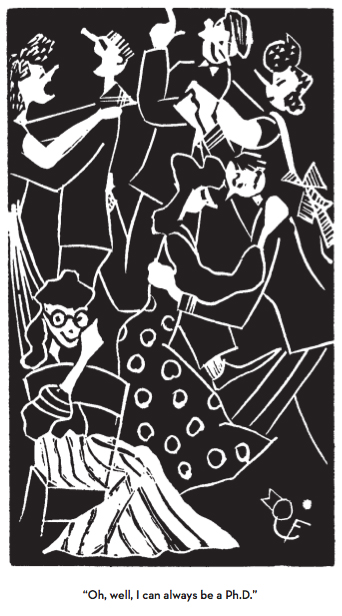

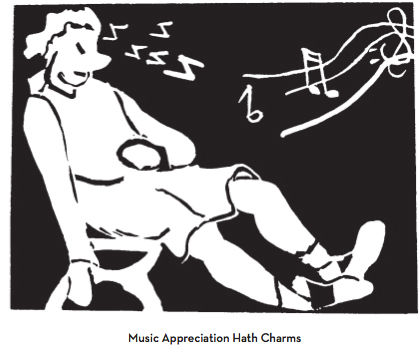

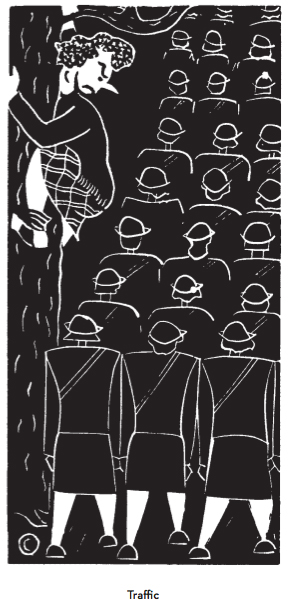

O’Connor started drawing cartoons at five years old, and by the time she began high school cartooning was her primary interest. Throughout high school and college—at Georgia State College for Women—she published satirical cartoons in her schools’ newspapers, making fun of school programs, her fellow students, and, later, the effects of WWII on student life, like the military training school implemented at Georgia State.

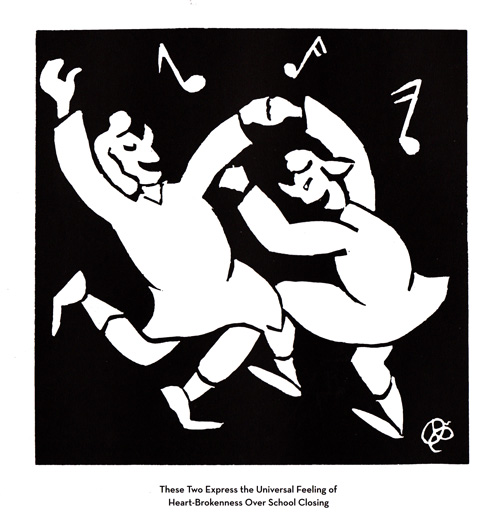

O’Connor made most of her cartoons from linoleum block cuts, and they have a distinct style—simplistic and full of character. According to Flannery O’Connor: The Cartoons, edited by Kelly Gerald, her students loved O’Connor’s talent for picking a few details and running with them: said former Georgia State student Gertrude Ehrlich, “[O’Connor] was a genius at depicting us ‘Jessies’ running around campus, with scarves hanging out of pockets, or messily draped on our heads.”

O’Connor’s cartooning style—both her lacerating humor and visual sensibility—would translate to her later writing. As Gerald notes in Flannery O’Connor: The Cartoons, O’Connor had a tendency to identify characters in her prose via one or two cutting, exaggerated visual details, like the characters in the doctor’s waiting room in “Revelation” (e.g. “the woman with the snuff-stained lips”) or on the bus in “Everything That Rises Must Converge” (“the thin woman with protruding teeth and long yellow hair,” “the woman with the red and white canvas sandals.”) The dynamics she dramatized in her stories were made clear through visuals: Julian’s mother (white) growing upset at a Black mother wearing the same purple and green hat as her in “Everything That Rises Must Converge” tells a reader everything they need to know about Julian’s mother.

O’Connor knew vision was central to her work. In an academic lecture on writing, O’Connor voiced her belief that “for the writer of fiction, everything has its testing point in the eye, and the eye is a whole organ that eventually involves the whole personality, and as much of the world as can be got into it.” It’s a happy reminder: your different types of art can inform and assist each other. No matter what disciplines make up your body of work, it’s still all made by your body.

[h/t Brain Pickings, The Paris Review]