To say there are “two Americas” immediately calls to mind any number of great sociocultural divides—Black/white, rich/poor, urban/rural—but one of the abiding tensions in this country has long been between civic conformity and individual eccentricity; or, if we are to locate these ideas as places in the American imagination: Suburbia and Bohemia. This particular divide—very broadly speaking—also falls across two halves of the 20th century, from the chaotic, disastrous extremes of the first to the stultifying desire for “normalcy” that filled much of the second.

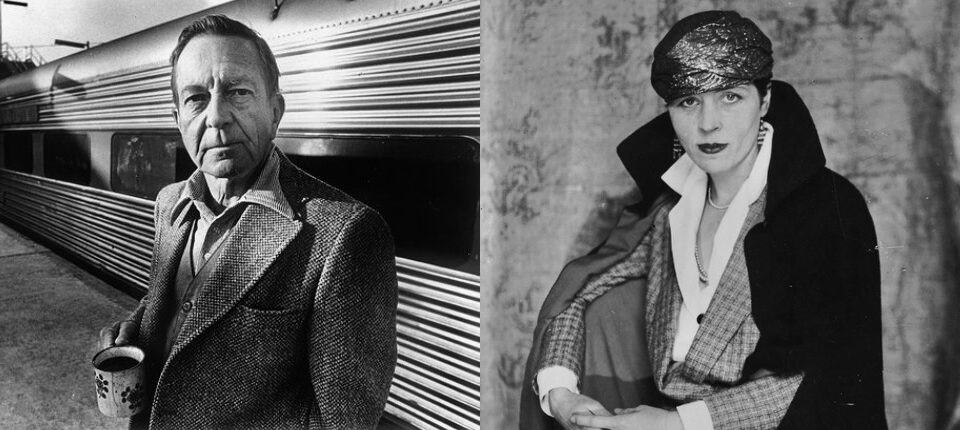

Suburbia vs. Bohemia also happens to be embodied by two of America’s great writers, who, as fate would have it, died on June 18, 1982. John Cheever and Djuna Barnes.

Not only were Cheever and Barnes adept in the fictionalized chronicling of their respective milieux, their very lives read like Gumpian film treatments, hastily written anti-hero journeys through archetypal landscapes, the one lined with decorous lawns, the other lived in a series of smoke-filled garrets, the only thing common to the two being ample amounts of semi-chilled gin.

*

Djuna Barnes was born in 1892 (in a cabin on Storm King Mountain!) to a radically bohemian family held together by her politically adventurous grandmother, an artistically inclined suffragist name Zadel Barnes. Djuna’s father, Wald, indulged by his mother as an “artistic genius,” seemed only to have a talent for earning little and fucking a lot; he was proudly polygamist and had five children with Barnes’ mother Elizabeth (Djuna, Thurn, Zendon, Saxon, and Shangar), and four with his mistress (Muriel, Sheila, Duane, and Brian). It is easy to see who had the flare for naming in the family.

As is often the case with those who make bohemian “lifestyle choices,” the adults in the young Barnes’ life seem like criminally indulgent assholes who just wanted to fuck and get fucked up without consequences; it is unsurprising, then, that the 20-year-old Djuna—after a brief, two-month marriage to her stepmother’s 52-year-old brother!—got the hell out and headed to Greenwich Village in 1912 (which probably seemed conservative to her after all that).

It’s almost as if Barnes chose to live in denial of America’s post-war drift into neverending consumption, choosing as she did to shut herself away from the Cold War era’s car-centric lionization of patriotic conformity.

From there, Barnes’ story is slightly more conventional… but not by much! After studying art at Pratt she dove into the writing life, strongarming editors with a charm and moxy that would see her career flourish in the latter half of the decade (she got her first job at the Brooklyn Daily Eagle after telling the editor “I can draw and write, and you’d be a fool not to hire me.”)

Barnes also seems to have experimented in what, five decades later, would be called “new journalism,” as she dove into an immersive, experiential style of reporting that must have shocked the more genteel readers of the time: she allowed herself to be “force-fed” in order to write about the torture of imprisoned suffragists, fictionalized a conversation with a celebrity gorilla at the Bronx Zoo, and admitted to boredom (in print) during an interview with James Joyce. Meanwhile, after work, she hung out with a who’s who of Greenwich Village bohemians, writing experimental plays, sleeping with men and women alike, and otherwise living out the values her family had only aspired to; she would later tell a friend that she “had no feeling of guilt whatever about sex, about going to bed with any man or woman she wanted.”

Barnes’ writing led to a life-changing assignment when McCall’s sent her to Paris in 1921 to write about the post-war scene… she stayed for a decade. As it did for so many of the so-called Lost Generation, the Paris of the Roaring Twenties intoxicated Barnes with its radical new frameworks for art, life, and politics, and she quickly became a fixture of the bohemian demimonde, revered and feared for her glimmering wit and black-clad intensity. It was in this adamantly cosmopolitan version of literary Paris that Barnes would develop the modernist style that defines her greatest work, Nightwood; it was also the place she’d meet the love of her life, an artist named Thelma Wood. But the 1930s (as was the case for most of the world) were not kind to Barnes.

Though she published Nightwood with TS Eliot at Faber in 1936, it didn’t sell very well. In the meantime, Woods’ alcoholism and infidelity weren’t particularly ameliorative of Barnes’ own issues with drinking, and Djuna eventually moved back to the states in 1940, where she was promptly sent by her family to a sanatorium for rehab.

Even though Cheever spent his thirties learning to be a writer in Manhattan, it seems like he was never quite able to get clear of the idea that success and happiness came with a lawn.

Barnes returned to Greenwich Village and settled into the long, reclusive second half of her life, writing a play in 1950, The Antiphon, and not much else (aside from hundreds if not thousands of poems, most of which went unpublished). Though writers like Carson McCullers, Anais Nin, and ee cummings made the pilgrimage to Barnes’ apartment on Patchin Place, she basically told them to go to hell.

When asked in her later years about her sexuality, Barnes liked to say, “I am not a lesbian; I just loved Thelma.”

It’s almost as if Barnes chose to live in denial of America’s post-war drift into neverending consumption, choosing as she did to shut herself away from the Cold War era’s car-centric lionization of patriotic conformity. If Barnes desired—as it seems she did—to live out her life as a citizen of her own bohemian memories, she did so in defiance of a new, aspirational America that saw only one way of life as desirable: the suburbs.

*

Enter John Cheever, two decades junior to Barnes, who was famously dubbed the “Chekhov of the Suburbs.” One needn’t make as thorough a case for Cheever’s preeminent position as a storyteller of the American suburban imaginary: no one (with the possible exception of Richard Yates, who’d been a prior renter of Cheever’s first suburban address in Westchester) has written so exhaustively, and with such painful intimacy, of the daily hypocrisies and muted pleasures of mid-century suburban existence.

In many ways, though Cheever was an early scion of the comfortable suburbs, his family’s fall from financial grace when he was in his teens shattered whatever rosy lens he might have had on the wide lawns and fine appointments of outer Boston. (I am sure that moving from a private day school to the local high school was equally revelatory for Cheever, who would’ve gotten an early taste of how toxically fluid certain kinds of American status can be.) Even though Cheever spent his thirties learning to be a writer in Manhattan, it seems like he was never quite able to get clear of the idea that success and happiness came with a lawn. And while it is risky to disinter the unhappiness of others, it is not hard to imagine Cheever finding more to like about himself in Barnes’ Greenwich Village, a place where he might have understood his repressed bisexuality as something other than the engine of his dread.

But that was not to be.

Cheever moved to Westchester in 1951, and settled for good a decade hence in the riverside town of Ossining. (After the glowing reception of his 1964 novel The Wapshot Scandal, Cheever was dubbed by TIME magazine as the “Ovid of Ossining.”) The 1966 release of The Swimmer, adapted from Cheever’s New Yorker story of the same name and starring Burt Lancaster, cemented his reputation for writing about the unhappiness of the comfortable and unafflicted, a condition he knew all too well.

Like Barnes, Cheever struggled his whole life with alcoholism, almost dying in 1973 of a pulmonary edema related to the condition. But after a brief stint in Iowa City teaching (and drinking) alongside Raymond Carver, and another teaching job in Boston, Cheever returned to Ossining, went into rehab, and was able to stay sober for the last seven years of his life.

*

June 18, 1982 was a day very much like today: high blue sky, 82 degrees, not too humid… perfect. Cheever, just turned 70, died of a lung cancer that had spread throughout his body; the flags in Ossining were lowered to half mast. Barnes, having made it against all odds to 90, died of something like natural causes (nobody’s really double-checking at that age).

Life owes none of us happiness, but some of us are luckier than others. Barnes and Cheever struggled their entire lives to figure out what it all meant, and though the former was able to accept—even embrace—who she was in a radical way, her increasing refusal to accept the wider world left her lonely and isolated, alive only in her memories. Cheever, on the other hand, never could accept himself, preferring instead to map his own unhappiness over the same world that Barnes rejected.

In the right circumstances they might have been something like friends, she the chronicler of bohemia, he the diarist of the suburbs. At the very least Barnes and Cheever might have recognized in each other the fellow writer’s need to sublimate pain into art, and in that found a sympathy they rarely—if ever—could muster for themselves.