Nathaniel Rich, Second Nature: Scenes from a World Remade

(MCD)

Writing about the climate crisis poses a strange kind of challenge to journalists used to working in the world of what is known: How do you tell the story of a future planet? While our lives, habits, and access to resources will profoundly change, and soon, Nathaniel Rich notes in Second Nature, “Our souls haven’t caught up.” Rich previously wrote Losing Earth, a damning account of the years that oil and gas executives hid their knowledge of the damage that fossil fuel emissions were causing from the public. Second Nature portrays the people addressing the challenges of a warming planet using technology, art, and business, with an eye toward environmental responsibility and the knowledge that no one really knows what happens next. –Corinne Segal, Lit Hub Senior Editor

James Merrill, A Whole World: Letters from James Merrill

(Knopf)

Even when James Merrill is at his most serious in his poems there is the occasional quicksilver glimmer in a line here, an image there, that speaks to what a goddamn delight he must have been in his daily life. How do I know this? It’s all there in his letters. Written to old friends and new, to family, to lovers, they are at turns profound, profane, absurd, gossipy, petty, quotidian, melancholic, funny… And unlike many other poets who (perhaps wisely) demanded their correspondence be destroyed after death, Merrill very deliberately wrote for posterity—apparently making carbon copies of his letters! (Though probably not the letter that kicks off the collection, in which the six-year-old Merrill asks Santa for a flashlight.) –Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub Editor-in-Chief

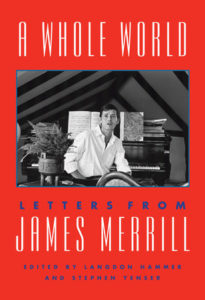

Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan, Francis Bacon: Revelations

(Knopf)

The artist Francis Bacon was a difficult, delightful, and brilliant man. Often defined more by his iconoclastic SoHo carousing than his decades-long devotion to revolutionizing the painted figure, Bacon finally has a complete biographical treatment that brings the two together in perfect formal balance. Pulitzer Prize-winning critic-biographers Mark Stevens and Annalyn Swan tell the full story of a man fearless in his art and in his life, who gloried in transgression, and refused to be anyone other than himself, whether it was out in London’s East End demimonde or sequestered in the chaos of his studio. If there was any doubt, Revelations shows us one of the great artists of the 20th century. –Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub Editor-in-Chief

Hanif Abdurraqib, A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance

(Random House)

Hanif Abdurraqib brings a singular poetic voice to this look at the history and soul of Black performance. Moving between different points in history, from Aretha Franklin’s funeral to Whitney Houston at the 1988 Grammy Awards to the basement of a Columbus bar, his book’s portrait of Black performance honors its ecstasy, its grief, its community-building power, and its sweeping influence on American culture. –Corinne Segal, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Brian Alexander, The Hospital: Life, Death, and Dollars in a Small American Town

(St. Martin’s Press)

Even in a year when the failures of the American healthcare system are painfully, catastrophically clear, Brian Alexander’s portrayal of a small-town hospital fighting for survival stands out. As Bryan, Ohio struggles to recover from the Great Recession, its hospital is floundering, with potentially disastrous consequences for the individuals that depend on it. Alexander’s account of what followed shows the many layers of predation and manipulation that ultimately make it impossible for many Americans to receive adequate care. –Corinne Segal, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Paul Sen, Einstein’s Fridge: How the Difference Between Hot and Cold Explains the Universe

(Scribner)

The first time I explained to my young son that heat and light were essentially the same thing, his little mind was blown. Then, of course, I wondered how accurate that really was. Every parent dreads the day their “wisdom” gets exposed for the half-remembered high school cheat sheet it really is, so I am grateful for Paul Sen’s fascinating new scientific history of thermodynamics—now I can explain my son’s two favorite things: fire and ice. The Laws of Thermodynamics were not a “discovery” by any one scientist but rather a multi-century compendium of observed phenomena gathered, tested, refuted, tested again, and finally codified. Throughout Einstein’s Fridge—which could be described as the biography of a theory—we encounter names that are more familiar as day-to-day concepts (Lord Kelvin, James Joule), alongside the visionary scientists like Einstein and Hawking who followed the inductive chain of thermodynamics into the deepest, most profound realms of speculation. Actually, maybe I’ll wait till my son turns 12 before I explain the heat death of the universe. –Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub Editor-in-Chief

Daniel Heller-Roazen, Absentees: On Variously Missing Persons

(Zone Books)

Daniel Heller-Roazen begins Absentees with an inquiry into the nature of personhood—specifically, how does someone stop being a person, whether biologically, in the eyes of the law, socially, or otherwise? His exploration of this question brings him to the worlds of philosophy, history, and even literature, as he looks to the missing characters of well-known narratives—Helen of Argos, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Wakefield, and others—for clues. Heller-Roazen’s project is an ambitious and engaging intellectual adventure for readers. –Corinne Segal, Lit Hub Senior Editor

Timothy Brennan, Places of Mind: A Life of Edward Said

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Timothy Brennan’s biography of the great Edward Said could just as well have been called The Many Lives of a Modern Intellectual: from orchestra impresario in Weimar to the New York intellectual cocktail set to the streets of Ramallah, the man whose critique of the Western gaze has been paradigmatic in the generations-long decolonizing project of the left, lived one hell of a life. And all of it recounted here through the eyes of former student and friend Brennan, whose understanding of the deep humanism that undergirded Said’s work illuminates a life’s project in important new ways. –Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub Editor-in-Chief

Juan Villoro trans. by Alfred MacAdam, Horizontal Vertigo: A City Called Mexico

(Pantheon Books)

Juan Villoro’s technicolor account of Mexico City is dizzying and vivid; navigating Villoro’s city is like wandering through someone else’s brain, synapses always firing and forming new pathways, memories flashing, feelings and impressions changing like traffic lights. From wild and chaotic market squares to sterile high raises, office boys to aged street vendors, Villoro introduces us to character and place, drawing the two together in a disordered pattern of a book. It’s like an ad hoc map based on directions from an infinite chorus of street-corner locals. –Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub Editor-in-Chief

Kale Williams, The Loneliest Polar Bear: A True Story of Survival and Peril on the Edge of a Warming World

(Crown)

The single doomed polar bear has long since lost its symbolic power to move us, so ubiquitous has it been on magazine covers and in news stories about the warming Arctic. But remember, each of those bears was a living, breathing, feeling creature, each one more vulnerable than the last, a vulnerability shared by any of us forced to flee our homes because of fire or flood, or find new jobs as climate change destroys our livelihoods… And this is perhaps the lesson of Kale Williams’s The Loneliest Polar Bear, the story of an abandoned polar bear cub named Nora, told in parallel to that of the very hunter who killed her grandfather in Alaska: the vulnerability of each of us is tied to the vulnerability of us all. –Jonny Diamond, Lit Hub Editor-in-Chief