Lawrence Ferlinghetti—a crucial supporter of the Beat movement and literary icon who bore a century’s worth of witness to social and political transformation—died on Monday at the age of 101 of interstitial lung disease, The Washington Post confirmed.

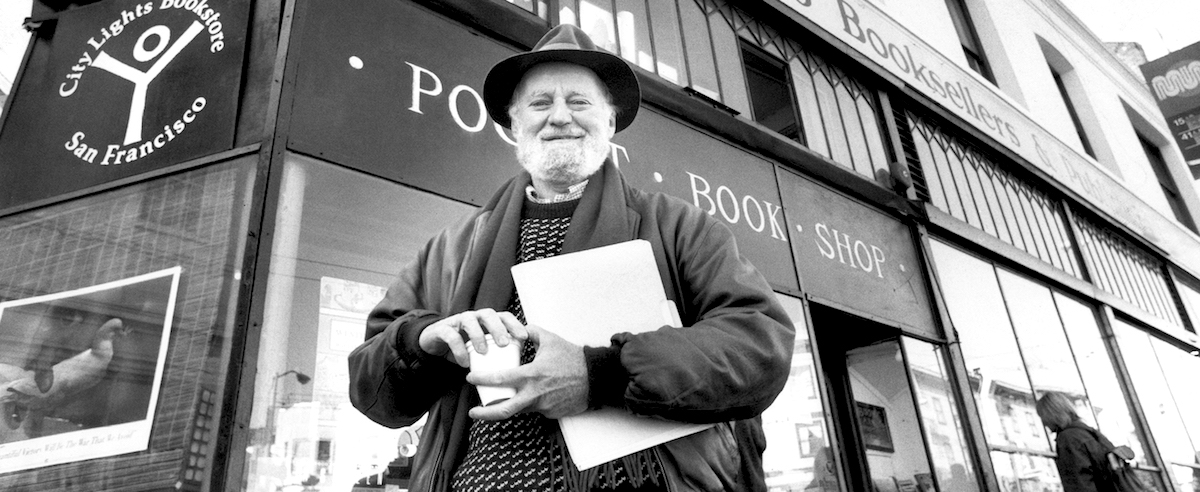

Ferlinghetti epitomized the soul of San Francisco counterculture for generations of artists and writers. As the founder of City Lights, a bookstore and publisher that grew from a small, avant-garde press to a literary institution, he provided a bedrock of support for scores of groundbreaking writers, staunchly defending the work that risked erasure and oppression from authorities.

Born in Yonkers, New York, in 1919, Ferlinghetti moved several times during his childhood—his father died before he was born and his mother entered a state mental institution before he was three years old. He lived in France, Bronxville, New York, and Massachusetts, where he attended the private high school Mount Hermon. Later, he earned a degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, drawn there by the fact that Thomas Wolfe had attended, before serving in the naval forces during World War II. After completing a master’s degree in English literature at Columbia University, he earned a doctorate in comparative literature from the Sorbonne.

Then, in 1951, he arrived in San Francisco, where his work would pave the way for a national literary movement while stoking a vibrant local literary scene. In a 2019 interview with The Paris Review, he described what he first encountered there:

When I arrived in town the only bookstores were like Paul Elder’s, downtown. None of them had periodicals. I felt right from the beginning there was no locus for the literary community. These bookstores all closed at five o’clock, they weren’t open on the weekend. What’s a literary person supposed to do, where is he supposed to go? From the beginning, when Peter Dean Martin and I started City Lights Bookstore in 1953, our idea was to create a locus for the literary community. We used to run a one-inch ad in the San Francisco Chronicle saying, “A literary meeting place since 1953.” That was our original line.

He also met literary critic and poet Kenneth Rexroth, whose show on the Berkeley community radio station KPFA captured his imagination. He told Interview in 2012:

He didn’t just review books, he knew every possible field-geology, astronomy, philosophy, logic, classics. It was a total education listening to him. It was a radical position. I used to go to his soirees on Friday night. There were a lot of poets that would show up. He lived in the Fillmore District, which was black at that time. He lived at 250 Scott Street, above Jack’s Record Cellar. Anyway, Friday night soirees at his house were old and young, but just poets. That’s where I met Kerouac and [Neal] Cassady and Gregory Corso . . .

Ferlinghetti and Martin each invested $500 to open City Lights Pocket Book Shop in 1953 at 261 Columbus Avenue. The store sold only paperbacks, a bold choice for a time when publishers were not particularly invested in the format; the decision reflected Ferlinghetti’s belief in making literature accessible to a mass audience. Two years later, he founded City Lights Publishers, aiming to encourage an “international, dissident ferment.”

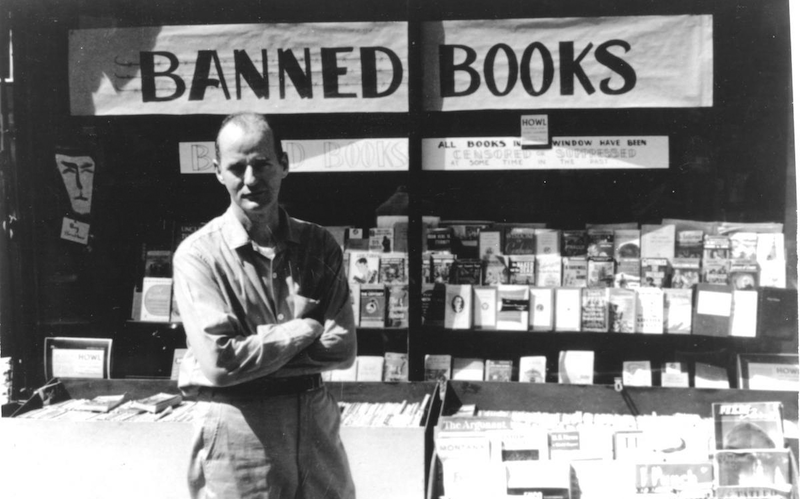

He first encountered Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” at a reading that same year. The following year, City Lights published it. (Ferlinghetti had given notice to the American Civil Liberties Union in advance.) Then, in 1957, he was arrested on an obscenity charge that a judge later dropped on the grounds that the poem had “redeeming social importance”; that decision would set a legal precedent for other authors who faced obscenity charges in subsequent years, including William S. Burroughs, D.H. Lawrence, and Henry Miller.

He notably did not think of himself as a Beat poet, though others would assign him the label throughout his life; in a 2006 interview with The Guardian, he called himself “the last of the bohemians rather than the first of the Beats.” Still, as a publisher of Ginsberg and many of his contemporaries, City Lights soon established itself as a vital publisher of progressive, experimental, and high-quality literary projects, working with other authors such as Jack Kerouac, Gregory Corso, Kenneth Patchen, Norman Mailer, Denise Levertov, Pauline Kael, Robert Duncan, and Frank O’Hara.

As a gathering space for artists and intellectuals, the City Lights Bookstore and its events, along with Ferlinghetti himself, became a hub of collaboration, artistic invention, and literary dialogue.

Ferlinghetti published more than 30 books of poetry in his lifetime. His work, including the well-known poem “Tentative Description of a Dinner to Promote the Impeachment of President Eisenhower,” often explicitly dealt with the social and political upheavals of the late 20th century—his collection A Coney Island of the Mind, published by New Directions in 1958, is one of the best-selling poetry collections of all time, according to City Lights. His other collections include Endless Life: Selected Poems (1981). These Are My Rivers: New and Selected Poems, 1955–1993, A Far Rockaway of the Heart (1997), Poetry as Insurgent Art (2005), and Time of Useful Consciousness (2012). He also published fiction, including the recent Little Boy, published by Doubleday in 2019.

City Lights said in a statement:

For over sixty years, those of us who have worked with him at City Lights have been inspired by his knowledge and love of literature, his courage in defense of the right to freedom of expression, and his vital role as an American cultural ambassador. His curiosity was unbounded and his enthusiasm was infectious, and we will miss him greatly.