John Rember, A Hundred Little Pieces on the End of the World (University of New Mexico Press)

Jeremy Garber, Powell’s, Portland: John Rember’s A Hundred Little Pieces on the End of the World collects ten essays about civilization’s ongoing (and ever accelerating) anthropocentric woes: climate change, overpopulation, fossil fuel dependence, the Sixth Extinction, consumerism, capitalism, etc. While many might read this book and mistakenly conclude it a panoply of pessimism, it is instead a work of pragmatism and realism, foregoing as it does any indulgences of pipe dream fantasies, magical thinking, or spurious promises of techno-salvation. Throughout A Hundred Little Pieces on the End of the World, Rember demonstrates not only a mordant wit and dark sense of humor, but also an all-too-rare ability to see things as they actually are, offering neither platitudes nor quick fixes (or even slow ones, for that matter). A Hundred Little Pieces on the End of the World is thought-provoking, reflective, and forthright—as well as being that freak book that actually lives up to its descriptive copy: “A collection of gentle-spirited wisdom and a rumination on ruin, as if distilled in equal measure from the spirits of Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road.”

Margarita García Robayo, Fish Soup, (translated from the Spanish by Charlotte Coomb, Charco Press)

Natasha Gilmore, Idlewild Books and Open Borders Books, NYC: This book contains two novellas and some short stories set around Colombia (and occasionally Miami). The narration is often low-affect, sharply cynical, and wryly observed. There’s a cutting honesty in the voice throughout the book that feels totally absent from so much literature now. It reminded me of the feeling of encountering something truly when I was a teenager. But then there’s just the crushing reality of coming into sexuality as a teen, colorism and racism in Colombia, the restlessness wrought by capitalism and the desire to flee yourself and the accidents of your birth that ultimately coalesce into something so universally resonant, that will make any reader feel seen and connected. Truly an author worthy of attention.

Maggie Tokuda-Hall, The Mermaid, The Witch, and The Sea (Candlewick)

Jacqueline Izzo, Books Are Magic, Brooklyn: The Mermaid, The Witch, and The Sea is one of my favorite YA books of 2020. In short, genderfluid Black pirate and queer Japanese noblewoman fall in love on a menacing pirate ship. Of course, I adore this book for its diversity, but above all I think it is top-tier adventure storytelling. I try to handsell this one whenever I get a chance because it’s one of those under the radar books that deserve more attention. I recommend it to anyone who desires a high-seas fantasy romance with brilliant POC and LGBTQIA+ representation.

Fowzia Karimi, Above Us the Milky Way (Deep Vellum)

Rick Simonson, Elliott Bay Book Company, Seattle: A book which at once has the soul of childhood and of an older soul leavened and weathered by exile and tragedy, this book has a narrative voice (and beautiful physical form) unlike any other encountered this year. It is the story of five young sisters, their mother, their father—forced to abruptly flee their homeland, then of life in the new land they arrive in. No one or place is ever named, but reading this you will know. The horrors being perpetrated in their homeland follow them in the form of heart-rending stories and news accounts, this while each of the five sisters is growing into life and ways of knowing, the parts of them that they come to know as themselves, but also as parts of a larger whole. Elements and forces beyond the human are a big part of this deep-hearted book, including the sky that is, after all, above us, over it all.

Paul Yoon, Run Me to Earth (Simon & Schuster)

Shuchi Saraswat, Brookline Booksmith: Whenever I read a novel or stories by Paul Yoon, I’m reminded of the vital power of fiction. Yoon is an attentive writer who understands the meaning in gestures, silences, objects, how, for some, memory lives on the surface. His characters are so alive that I’m certain they’re real or that maybe I’ve even met them before. In Run Me to Earth he takes us to 1960s Laos and into the lives of Alisak, Noi, and Prany, three teenagers working in a hospital surrounded by buried, unexploded bombs. We meet them at a moment when their lives have found a kind of rhythm and what unfolds over their time at the hospital runs like a current through the rest of the novel, pulling us through decades and across continents. This is another stunning novel by one of our best fiction writers.

Nate Marshall, Finna (One World)

Jeff Deutsch, Seminary Co-op and 57th Street Books, Chicago: Nate Marshall’s poems are a gift. In this follow-up to his brilliant debut collection, Wild Hundreds, Marshall continues to exhibit a preternatural talent for observation, rhythm, and form. I couldn’t stop reading and re-reading this book since it was released this summer. It is a celebration, a lament, and a tremendous literary achievement. It will be read for generations.

Tomás Gonzalez, Difficult Light (translated by Andrea Rosenberg, Archipelago Books)

Mark Haber, Brazos Bookstore, Houston: A quiet and modest novel that struck me with its lovely prose and profound insights. An aging painter looks back at the loss of his son Jacobo, as well as the inevitable sorrows that accompany aging. Yet Gonzalez focuses on the glimpses of beauty, the shards of light found in the everyday. A thoughtful meditation on art, family and loss; this slim novel reads like an afternoon reverie, hazy, supple, tinged with sadness and joy.

Scott Russell Sanders, The Way of Imagination: Essays (Counterpoint)

Karen Maeda Allman, Elliot Bay Book Company, Seattle: Scott Russell Sanders’s essays left me thinking deeply about the role of faith in understanding our relationship with the natural world, and our place in it. Isn’t there a different way forward, into restoration of the earth and of our relationships with each other, he asks? His words are gentle, hopeful, and wise, a counterpoint to harshness and giving in to the “inevitable.” Reading this book felt to me like reading a prayer. And prayer, in many faith traditions, also requires humility, taking responsibility and taking action.

Jazmina Barrera, On Lighthouses (trans. Christina MacSweeney, Two Lines Press)

Kar Johnson, Green Apple Books on the Park, San Francisco: No one could have predicted how fitting a text On Lighthouses would be during this completely unpredictable year, and because of the time I spent with this book I came to consider it a companion. Jazmina Barrera presents the history of lighthouses and their cultural significance to engineers, explorers, authors, and auteurs, but through her personal fascination with the lighthouse she charts our wide-reaching and most human concerns. As a collector of trinkets and memories, Barrera brings us evocative explorations of our need for direction and documentation, the differences in loneliness and solitude, the anachronisms among us, and the artifacts we make of ourselves. This book was very helpful during early shelter-in-place orders when I so desperately needed to make a distinction between days, harkening to a lighthouse keeper’s need to make the monotonous somehow memorable (“When time is indefinite, the calendar and the clock become indispensable to avoiding paralysis”).

I found something spiritual and meditative in Barrera’s wise contemplation and the contradictions necessary in a lighthouse—its smallness and stillness in the face of the large and lively sea, the isolation of its keeper tasked with guiding others to safety. “Impossible to imagine a lighthouse without including the sea,” she writes, “They are a single entity but also opposites.” During this time, when we need to isolate to stay safe and we need to connect to stay sane, it felt comforting to be in the mind of a brilliant writer and her faraway obsession. Translated marvelously by Christina MacSweeney, Barrera gives us beautiful, resonant sentences throughout. Every page was rich and illuminating, and spoke to a deep curiosity I didn’t know I had. I am grateful I had this book to keep me company when I needed it most.

Leslie Kaplan, Disorder: A Fable (translated from French by Jennifer Pap, published by AK Press)

Emma Ramadan, Riffraff, Providence: All over France, a string of murders takes place, and there seems to be a clear connective thread. A bank teller, a model employee of the branch for 25 years, suddenly drops a safe on his manager’s head. A personal driver crashes his employer into a wall. A woman working at a beauty counter whacks the male head of the women’s department with a metal stool. An immigrant warehouse worker drops a giant sack of coffee on his boss. A young female library employee who’s just organized an exhibition on colonialism hits a minister in the face with a bottle of champagne at the grand opening. “Experts” and “researchers” all desperately seek an explanation for these “inexplicable” acts of violence and rage. What could the reason for these crimes possibly be?! A tremendous commentary on the state of the world that’s as playful as it is dark and incisive.

Josep Pla, Salt Water (translated from Catalan by Peter Bush, Archipelago Books)

Lesley Rains, City of Asylum Bookstore, Pittsburgh: Taking refuge in a remote location sounds pretty appealing in 2020. In the 1940s, Josep Pla lived in a self-imposed exile in Catalonia’s Costa Brava. The result is Salt Water, a genre-blending collection of stories about his time sailing, eating, and moving among the region’s small towns. Readers will be drawn into Pla’s evocative descriptions of the coastal environment, surly sailors, shipwrecks, and, above all, Catalonia’s rich food and drink. In Peter Bush’s lively translation, Salt Water is a reminder that being alone doesn’t mean being lonely.

Jessica Anthony, Enter the Aardvark (Little Brown and Company)

Elayna Trucker, Napa Bookmine, Napa: This book is absolutely bonkers and I loved it. The narrative is split into two alternating sections: the first, told in the second person, is about a closeted gay Republican Congressman—think a slightly more self-aware, slightly less insane Patrick Bateman. The second, told in the third person, features a taxidermist in 19th-century England who is working through the depths of grief to taxidermy the first aardvark seen outside of Africa. These disparate characters have much more in common than is first apparent, as their stories weave around and intersect with each other. Many parts of this satire are laugh out loud funny, though it’s about the utmost serious topics of self-hatred, denial, societal expectation, and American political hypocrisy. I have no idea how Jessica Anthony managed to come up with this crazy book, and even less how she executed it so well in fewer than 200 pages.

Tracy O’Neill, Quotients (Soho Press)

Jeff Waxman, Open Borders Books and The Bookstore at the End of the World: I was thinking this over, trying to parse what it meant for a book to be really overlooked, when I read that John le Carré had died. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold was the first, best spy novel I ever read, and though he’s written equal numbers of forgettable airport novels and timeless classics since, that book will always, always, loom incredibly large for me. And with his work in mind, I thought back to the early days of this nasty year, before the quarantine and isolation, before I was furloughed from a Brooklyn bookstore, and before I found myself forming new bookselling endeavors like Open Borders Books and The Bookstore at the End of the World, back to when I took home a fat ARC called Quotients. Like le Carré, Tracy O’Neill seems to thrive in the murk, in the space between appearance and reality, and Quotients delves deep into the clouds of unknowing that surround information and identity and the amorphous worlds of government and capital.

Me, I’ll pick up any book about the interconnected machinery of state violence and business, but O’Neill elevates this story into an alienated emotional place that reminds us that global agendas are enacted by real people with personal lives, who care about others and are loved in turn; O’Neill’s protagonists, Jeremy Jordan and Alexandra Chen, are flawed and real, in love, and hopelessly enmeshed in relationships bigger than the one they share. I have a dread fascination with these tense and twilight worlds, and the intimacy and verve that O’Neill brings back to an almost exhausted genre is really worthy of far more attention than it’s received.

Jason Guriel, Forgotten Work (Biblioasis)

James Crossley, Madison Books: When I chose this as my overlooked book for 2020, I didn’t think at all about the aptness of its title. Published in the fall, it hasn’t been out long enough to be truly lost yet, but it’s definitely flown under the radar. I didn’t see a single review of it, at any rate. Which might be the most brilliant marketing tactic ever, come to think, since Forgotten Work is about a lost artistic maybe-masterpiece. The setup is that a rock band with few resources but big ideas forms in the early 2000s, makes one recording, and then vanishes. A half-century later, in a world dominated by corporate technology, a coterie of vintage fetishists obsess over the band’s songs, known to them only through the writing of an obscure music critic. All very meta, concerned with the true meaning of art and authenticity, and crammed with references to the likes of Nabokov and Nick Drake. All very amusing, too, mocking its seriousness as it goes.

Oh, and I buried the lede: Forgotten Work is a novel in rhymed verse, heroically unspooling perfect couplets for almost 200 pages. It’s an SF epic poem, an excellent ekphrastic entertainment for English majors, a figment of imagination made real, and the perfect discovery to make for yourself in the hidden corner of your favorite bookstore.

Cristina Rivera Garza, Grieving: Dispatches from a Wounded Country (trans. Sarah Booker, The Feminist Press)

Nika Jonas, Books Are Magic, Brooklyn: I’ve been looking for an opportunity to recommend this book from the moment I read the introduction. A collection of crónicas and essays, Grieving probes the violence of contemporary Mexico and its border with the US with startling clarity, asking what it leaves behind and what literature can do in its wake. Understandably, a lot of people haven’t been in a place to engage with such heavy material this past year, but for anyone who feels up to it this is absolutely the book you should be reading. Grieving is deeply thought-provoking and beautifully written, which is no surprise to anyone familiar with Cristina Rivera Garza, who is brilliant. I cannot recommend it enough.

Julian Herbert, Bring Me the Head of Quentin Tarantino (translated by Christina MacSweeney Graywolf Press)

Javier Ramirez, Exile in Bookville, Chicago: Bring Me the Head of Quentin Tarantino reminds me of a favorite mix-tape, one architect bringing a plethora of great ideas together in perfect sequence in order to make something wonderful. The opening selection puts the reader in a frame of mind that’ll set the pace for the rest of the collection, culminating in the title story that would make the famed director in question envious. One thing is for sure, you won’t think of Mother Teresa or watch a Quentin Tarantino film the same way again.

Al-Ḥarīrī, Impostures (translated by Michael Cooperson, New York University Press)

Brad Johnson, East Bay Booksellers, Oakland, CA: I’m selecting a book that might have gone under the radar even without a pandemic! Reading fiction was something of a chore for me this year, but Impostures was unlike any other fiction I’ve read since Herman Melville’s defiantly weird The Confidence-Man. Similarly themed, it focuses on a shape-shape-shifter, a con-artist, for whom language disguises far more than it ever truly reveals … maybe. The wonderful thing about Michael Cooperson’s translation is that revelation is not only in the eye of the beholder, but also the perspective of that beholder. This is one of the real accomplishments of literary translation this (or any!) year.

Mary Cappello, Lecture (Transit Books)

Clancey D’Isa, Seminary Co-op Bookstores: There were many things missed this year: time with friends, gathering with family, the joy of being among strangers, communal celebration, browsing in bookstores. Yet, one such form of togetherness, nearly forgotten to me, was given new life in Mary Cappello’s book Lecture. In Lecture, Cappello creatively argues for the art of the lecture, a form that spurs not just note taking but, also, observation, excitement, a voicing of song, a dream. The writings and lectures of Virginia Woolf and Mary Ruefle and John Cage, among others, serve to underpin this book—the first in Transit’s Undelivered Lecture Series. It’s through her exploration of the lecture’s importance that Cappello comes to discern that the lecture is neither an object nor an essay; instead, the form is an invitation to “tempt our lives towards something more than a dim assemblage of rote transactions and automated teachings towards a cellphone.” Indeed, the lecture is not to be missed—and even in its virtual form may offer something eminently human.

Max Gross, The Lost Shtetl (Harper Via)

Danny Caine, Raven Bookstore: I really loved Max Gross’s The Lost Shtetl, but alas, with no customers in our store since March I haven’t had as many opportunities to evangelize about it as I should have. The Lost Shtetl is a hilarious and poignant alternate history parable set in Kreskol, a totally isolated Jewish town in Poland that somehow escaped the Nazis. In fact, Kreskol has escaped all of modern history. In the present day (which doesn’t really resemble the present day anywhere else), a nasty Kreskol divorce turns into a missing-persons case. Facing no other choice, the town decides to dispatch schlumpy teen Yankel Lewinkopf to the nearest town to alert the authorities. That’s when the authorities learn that Kreskol even exists. The resulting consequences for the tiny town become a clever and satisfying yarn of a novel. Perfect for fans of Gary Shteyngart or The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, The Lost Shtetl is a welcome new entry into the rich tradition of Jewish comic novels.

Gary Indiana, Depraved Indifference (Semiotext(e))

Hal Hlavinka, Community Bookstore: Yes, I’m nominating a reprint of a novel, but hear me out: Gary Indiana is the greatest living American novelist that you’ve never read, and Depraved Indifference is a perfect entry point into his nigh flawless body of work. Now, more than ever, it’s a book for our moment, a novel filled to bursting with grifters, hustlers, liars, cheats, thieves, swindlers, and murderers; about crimes both everyday and historic, sometimes both at once; about the tendency of all things towards ruin, disgrace, collapse, decay. Plus it’s technically true crime, if you do a little digging, so finger really on the pulse. What started with Melville’s The Confidence Man finds its terminus in Indiana’s apocalyptic—and very funny—vision. It’s the vibe of now.

John Freeman, Dictionary of the Undoing (MCD & FSG Originals)

John Evans, DIESEL, A Bookstore, Brentwood: What does a contemporary civility even look like? Editor, writer, poet John Freeman somehow managed to quietly engage the world (in 2019, pre-Covid) so that he could articulate his thoughts on the commons, on justice, on civility and the language we use to talk with each other about it. It is a conversational corona of essays, in alphabetical order, each building on the previous ones to construct a language with which to speak about our ability to live well together. Saving language itself from the predations of party politics, corporate manipulation, and media distortion, he calmly and poetically enlivens our vocabulary, accessibly restoring values, heart, and feeling back into the mix. This is the one book this year that I wish everyone would take some thoughtful moments to read. And then share it with friends so that we can talk differently, to act differently, to create differently, our world.

Kawai Strong Washburn, Sharks in the Time of Saviors (MCD)

Robert Sindelar, Third Place Books: This is such a deeply felt novel of family and place. It is rich with deep power of folktales and spirituality and has a lot to say about the American Dream in our current landscape. I fell in love with this family and mourned having to say goodbye to them.

Garous Abdolmalekian, Lean Against This Late Hour (Penguin Poets)

Serena Morales, Books Are Magic: At a time when everything felt important and urgent but nothing felt easy, especially not reading, these poems drew me in and swept me clean off my feet. This dual-language collection features, for the first time, English translations—courtesy of Ahmad Nadalizadeh and Idra Novey—of Abdolmalekian’s work alongside their original Persian script. The poems here deal with matters of war, loss, violence, and surveillance, through images that are at once surreal and deeply familiar, which gives the collection an overall cinematic quality. Told in lyrics that are spare but quite stunning and viscerally-felt, this collection will resonate for both poet enthusiasts and novices alike.

Pergentino José, Red Ants (translated by Thomas Bunstead, Deep Vellum)

Angela Spring, Duende District: A compelling, powerful collection of poetic short stories by Pergentino José, of the Zapotec people, Red Ants pushes the boundaries of our colonized Othered gazes and drops you into a brilliant and waking dreamlike worldscape that takes you on journeys searching for lost children and imprisoned men and women, from coffee plantations and jungle to the city.

Francois Dominique, Aseroe (translated by Richard Sieburth, Bellevue Press)

Samuel Partal, Community Bookstore: One man’s erotic obsession with a grotesque—and pungent—mushroom. It begins in a forest, with an occult recitation literally vomited into the soil, and continues across multiple cities as our nameless narrator whiles away the days reading in empty bars, following strangers home, and suffering a dissociative episode in the face of a painting by Giorgione.

Judith Schlansky, An Inventory of Losses (translated by Jackie Smith, New Directions)

Molly Parent, Point Reyes Books: In a year when I found myself doing a lot of thinking about loss, memory, and time (you too?), An Inventory of Losses by Judith Schlansky was a perfect companion. Each of these essays is about something that no longer exists (a species of tiger, poetry of Sappho, an encyclopedia carved in chestnut trees). For me, it served as a necessary reminder that the world is big and life is long.

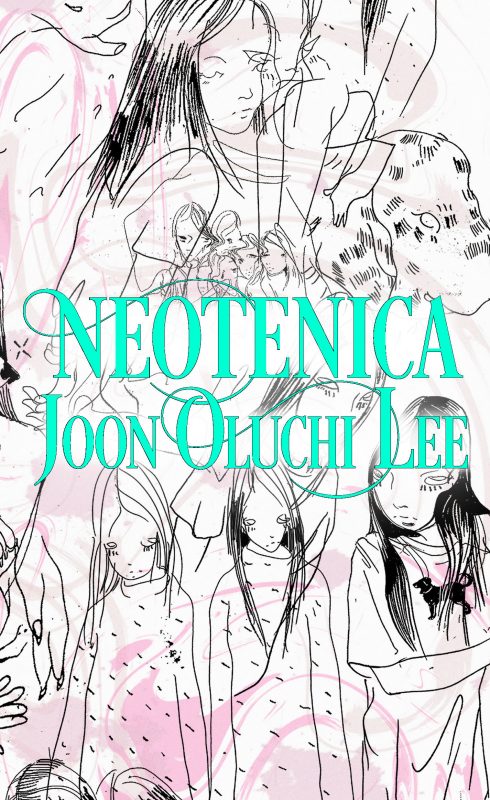

Joon Oluchi Lee, Neotenica (Nightboat Books)

Cristina Rodriguez, Deep Vellum: Neotenica is a tiny masterpiece. It’s rowdy, alarming, sexy, and gives a deeper exploration of the messy, discursive texture of everyday life. Joon Oluchi Lee has written a novel with such verve and tenderness that you will become obsessed by page one.

Deb Olin Unferth, Barn 8 (Graywolf)

Julie Wernersbach, Book Revue, Huntington, NY: A rag-tag group of characters stumbles together to free factory-farm chickens in this novel of activism, personal reckoning, and chicken capers. Unferth’s wit lies in the unexpected, whether it’s a surprising turn-of-phrase or a plot twist you never saw clucking. The cruel realities of the poultry industry are laid bare alongside big existential questions: How do you move forward when your life has bottomed out? What does saving the world—or yourself—really look like? How many trucks do you need to move a few hundred chickens? You have not read another book like this one, I promise you. The best description I heard of it was from one of the Graywolf reps at Winter Institute, who described it as something like a vegan Ocean’s 11, with chickens. A fun, funny, and thought-provoking read.