Emergence Magazine is a quarterly online publication exploring the threads connecting ecology, culture, and spirituality. As we experience the desecration of our lands and waters, the extinguishing of species, and a loss of sacred connection to the Earth, we look to emerging stories. Each issue explores a theme through innovative digital media, as well as the written and spoken word. The Emergence Magazine podcast features exclusive interviews, narrated essays, stories, and more.

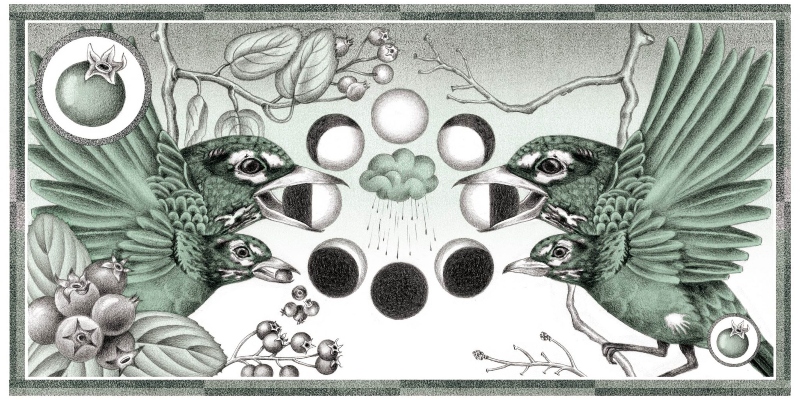

As Robin Wall Kimmerer harvests serviceberries alongside the birds, she considers the ethic of reciprocity that lies at the heart of the gift economy. While the free market system we embrace in the United States touts individualism and defines value by monetary worth, a gift economy functions through an ethic of reciprocity and interconnection. How, she asks, can we learn from Indigenous wisdom and ecological systems to reimagine currencies of exchange? “Thriving is possible,” she writes, “only if you have nurtured strong relations with your community.”

From the episode:

In Potawatomi, it is called Bozakmin, which is a superlative: the best of the berries. I agree with my ancestors on the rightness of that name. Imagine a fruit that tastes like a Blueberry crossed with the satisfying heft of an Apple, a touch of rosewater and a miniscule crunch of almond-flavored seeds. They taste like nothing a grocery store has to offer: wild, complex with a chemistry that your body recognizes as the real food it’s been waiting for.

For me, the most important part of the word Bozakmin is “min,” the root for “berry.” It appears in our Potawatomi words for Blueberry, Strawberry, Raspberry, even Apple, Maize, and Wild Rice. The revelation in that word is a treasure for me, because it is also the root word for “gift.” In naming the plants who shower us with goodness, we recognize that these are gifts from our plant relatives, manifestations of their generosity, care, and creativity. When we speak of these not as things or products or commodities, but as gifts, the whole relationship changes. I can’t help but gaze at them, cupped like jewels in my hand, and breathe out my gratitude.

In the presence of such gifts, gratitude is the intuitive first response. The gratitude flows toward our plant elders and radiates to the rain, to the sunshine, to the improbability of bushes spangled with morsels of sweetness in a world that can be bitter.

Gratitude is so much more than a polite thank you. It is the thread that connects us in a deep relationship, simultaneously physical and spiritual, as our bodies are fed and spirits nourished by the sense of belonging, which is the most vital of foods. Gratitude creates a sense of abundance, the knowing that you have what you need. In that climate of sufficiency, our hunger for more abates and we take only what we need, in respect for the generosity of the giver.

If our first response is gratitude, then our second is reciprocity: to give a gift in return. What could I give these plants in return for their generosity? It could be a direct response, like weeding or water or a song of thanks that sends appreciation out on the wind. Or indirect, like donating to my local land trust so that more habitat for the gift givers will be saved, or making art that invites others into the web of reciprocity.

Gratitude and reciprocity are the currency of a gift economy, and they have the remarkable property of multiplying with every exchange, their energy concentrating as they pass from hand to hand, a truly renewable resource. I accept the gift from the bush and then spread that gift with a dish of berries to my neighbor, who makes a pie to share with his friend, who feels so wealthy in food and friendship that he volunteers at the food pantry. You know how it goes.

To name the world as gift is to feel one’s membership in the web of reciprocity. It makes you happy—and it makes you accountable. Conceiving of something as a gift changes your relationship to it in a profound way, even though the physical makeup of the “thing” has not changed. A wooly knit hat that you purchase at the store will keep you warm regardless of its origin, but if it was hand knit by your favorite auntie, then you are in relationship to that “thing” in a very different way: you are responsible for it, and your gratitude has motive force in the world. You’re likely to take much better care of the gift hat than the commodity hat, because it is knit of relationships. This is the power of gift thinking. I imagine if we acknowledged that everything we consume is the gift of Mother Earth, we would take better care of what we are given. Mistreating a gift has emotional and ethical gravity as well as ecological resonance.

________________________________

Listen to the rest of this story on Emergence Magazine’s website or by subscribing to the podcast.

Robin Wall Kimmerer is a mother, scientist, professor, and enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. She is the author of Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. Kimmerer lives in Syracuse, New York, where she is a SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor of Environmental Biology and the founder and director of the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment.

Christelle Enault is an artist and illustrator based in Paris. She illustrates for major newspapers, including Le Monde, The New York Times, and Libération, and for publishing houses, including Actes Sud Junior and Albin Michel. She spends her free time in the natural world, collecting and drawing plants.