It seems appropriate for me to reflect first on the undistinguished chair I’m sitting in as I try to put together a few words to introduce you to this biography of Richard Nelson. I bought the chair long ago in a second-hand store, in Springfield, Oregon. I’ve had to repair it occasionally, to ensure its sturdiness. Two worn-out seat cushions, one atop the other, make it easier to occupy for hours at a time. Two newel posts brace a tapered backrest of wooden spindles. The caps of the newel posts gleam from the rub of human hands over the decades.

I’ve written seventeen books sitting in this chair, and I hope to complete a couple more in the years ahead. In the early 1980s, because I sensed that resting my back against a pair of cured blacktail deer hides from Richard’s hunts would put me in a more respectful frame of mine when I wrote, and that they might induce in me the proper perspectives about life, I wrote him and asked for his help. Would he honor our friendship by sending me a couple of blacktail deer hides? These were from deer he’d been given as a subsistence hunter (as he understood that relationship with them) in the woods near his home.

In my experience, no other non-native hunter’s ethical approach to this archetypal form of fatal encounter was as honorable as Richard’s. He hunted to feed his family, imitating the way his Iñupiaq, Koyukon, and Kwich’in teachers had taught him to, through the example of their own behavior in engagements with wild animals—humble, grateful, respectful. I felt the hides might care for me as I stumbled my way through life, in the same way that our friendship with each other would take care of both of us in the years ahead.

So, this morning, I am sitting in front of my old typewriter with my back against those soft hides, and I want to say a few things about this extraordinary man, Richard K. Nelson, most of whose friends called him simply Nels. I think of him as remarkable among Western anthropologists who have apprenticed themselves to traditional people because, as a young man, he took on with fierce dedication in discouraging circumstances a journey few people have ever had the opportunity to experience, and he pursued that journey with great attentiveness and care for more than 50 years. He listened to his teachers, immersed himself in their landscapes as a naturalist, and became, without intending to, a great teacher himself.

What Nels modeled was a way of knowing the world, an epistemology different from the one most of us have unconsciously accepted and sworn ourselves to.It led him to reconsider what in his own life was to be valued over human exceptionalism, for example, progress for the sake of progress, or the manic accumulation of material wealth.

What Richard K. Nelson modeled was a way of knowing the world, an epistemology different from the one most of us have unconsciously accepted and sworn ourselves to.

Nels was a man who dedicated himself to an unending personal task—self-education—and who became, because of that, to use Hank Lentfer’s unusual but apt term, a kind of monk. He didn’t pursue life alone in a cave, staying out of touch with others and with the physical world, but became instead a carrier of wisdom from traditions he had known nothing about as a young university student. This is to say the wisdom of marginalized and vanishing hunter/gatherer cultures in remote parts of North America.

He came to understand, through decades of intimacy, applied study, and life practice, a frame of mind he was once innocent of, one based much more firmly on enduring human values like thinking respectfully about wild animals. As he wrote about this perspective in books and articles and as he began to speak publicly about other ways of knowing, he developed the aura of a person shaped by something on the far side of pedestrian reality. A monk, then.

We must recognize how often illumination came to Richard Nelson in the company of other people, to see the social dimension of the wisdom he offered to share with us. Over time, Nels slowly became someone more intent on listening than in advancing himself as a speaker. Iñupiaq people in the 1960s saw that this outlander from Wisconsin was willing to listen attentively and to work hard in order to acquire knowledge and field skills. By the time he arrived among the Koyukon in Huslia and Hughes in the seventies, he had learned to present himself as a listener, quintessentially, not a cultural anthropologist. As a result, the breadth of his learning widened and deepened.

By the time he was camping in Glacier Bay with Hank Lentfer, in 2016, he was listening to the world around him so closely he could differentiate between the seemingly identical calls of two fox sparrows in the same thicket. He could tell from the anxious behavior of a gray whale in a protected bay that orcas were swimming nearby, unseen. He understood that his professional position in life had moved beyond anthropology, good as he was at that, to a level of attentiveness to the nonhuman world that one of his Koyukon teachers, Lavine Williams, alluded to when he informed Nels one day in Hughes that “every animal knows way more than you do.”

The truth of Lavine’s remark was both allegorical and factual. To be patient, to pay attention to the world that is not yourself, is the first step in the neophyte’s discovery of the larger world outside the self, the landscape in which wisdom itself abides. Other residents of the world, Lavine was telling him, know more than we do about how to survive whatever is coming. Their investment is not in progress but in stability. Nels’s life became the passing on of this deceptively simple message about human survival. It was this message that he lived.

__________________________________

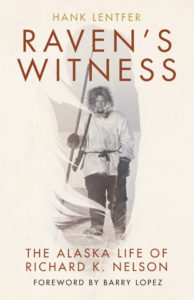

From Raven’s Witness: The Alaska Life of Richard K. Nelson by Hank Lentfer with a foreword by Barry Lopez. Used with the permission of Mountaineers Books.