A few days ago, I read the first chapters of the latest draft of a novel written by a friend. I had reviewed her previous book for the London Review of Books, at which time I didn’t know her. That was about eight years ago, and afterwards we developed a correspondence. I would ask how her new book was coming, and she would ask about mine. As always (for both of us) it was either going incredibly well, or incredibly badly.

I am always very interested in the process of other writers, in part because it reassures me that it’s always the same: moments of elation followed by moments of despair, tempered by the awareness that neither of these feelings offers any real information about whether our book is any good (although it’s hard for the feeling not to color our entire lives).

So, a week ago, I asked her if I could read her new stuff, because I was curious and thought I could help; I sensed she might need a fresh reader. She sent me the chapters, I read them, wrote a long email in response, she wrote me a long one back, and now my mind has been added to hers in the creation of her book. Yesterday I sent a draft of my current book to two friends, and I am waiting to hear what they think—if they think it is good or bad, or makes sense or doesn’t.

It’s always important to show a work in progress to more than one person at a time, so that nobody’s opinion is too influential. What if you show it to only one person and they hate it? And you believe them! Or they love it? And you believe them! Better to send it to two, three or four people, so that you can situate the truth about the draft somewhere along that range.

For me, friends who read drafts of my books are my most cherished readers. I feel as though they are more sensitive than any critic, or any reader of a finished book. They know they have to speak to me about it, and they care for me—so I know they care for the book. And it works the same way in reverse: I am never a more careful, thoughtful or open-minded reader than when I am reading a friend’s draft. I have to become part of their mind—add my mind to theirs—so I can’t just go into it with all my preferences and passing desires.

I think those who are not writers don’t have a sense of how much writers share their unfinished work with each other. Probably no fewer than 40 people read drafts of my books before they reach publication. It is in conversation with these writers that so much of the work is done: the work of moral support, the work of responding to the very high standards of my fellow writers, and writing with the knowledge that people I know and respect are going to have it in their hands. That’s a much scarier feeling than the thought of someone you’ve never met reading it.

I must read with a complete openness, a sensitivity to what this creature is trying to become.

Even before they respond to the work, I am reflexively imagining how the book will sit in their imagination. Often a friend doesn’t even need to read it in order for me to find them helpful; often, when I send it to another writer, I can suddenly see the book as (I imagine) it will seem to them. I can see everything that’s wrong with it, where it fails, where it succeeds, and I feel embarrassed, proud, apologetic.

Most of the time, before a friend even gets a chance to open the document, I write to them, Don’t read it! It’s not done! It was enough to have sent it. Then it hits me—suddenly and completely—how good or bad my book is, and I see the book anew, and am able to work on it with new energy, for several weeks.

The reader of the final, bound book reads in a frame of mind that is all about them: Is this what I want to be reading right now? If not, they (hopefully) throw it away. I am the same way. I feel no moral responsibility towards the books I buy in a bookstore. In a way, a book that has been published is already dead. It doesn’t matter to the book whether I like it or not; that doesn’t change it. It has achieved its final form.

I don’t have a responsibility to a writer I don’t know. I read more selfishly. I read with only my own pleasure in mind. But when reading a draft, when a fellow writer is waiting for my response, I have to read in as selfless a way as possible. It is not my own pleasure I have to pay attention to, but this little creature, developing. I am one of the forces that will help it achieve its final form—or fail to achieve it.

I must read with a complete openness, a sensitivity to what this creature is trying to become. It doesn’t have to please me. My task is more impersonal; it is about shedding my own tastes and trying to think about what the writer is trying to make—but hasn’t quite made yet.

We still have the idea that art is made by the artist alone, but from what I’ve seen, it is always made in a community of peers, of people chosen to play not a small part, but a part that affects the work hugely. These people are the first audience for one’s books. They are the chosen audience. If it doesn’t please these people, one feels the book will please nobody. But it is not only writers who write in a community of other writers. All artists work this way.

Critics are a necessity of the publishing industry, and readers are, in theory, who books are ultimately for. But no book can be for an unknown reader the way it is literally for the person you send it to, with hopes and fears and a looming question in your mind. In this way, in a sense, all art is made for other artists, and in response to their understanding and sensitivity. They are the most open-minded of audiences, for they know that art can—and must—take a multitude of forms; and they are the most discerning, for who cares more about the craft of novel-writing than another writer? Who cares more what happens to a painting—whether it achieves its sublime beauty, or its sublime ugliness—than another painter?

Yesterday I was in my friend Margaux Williamson’s painting studio. We have a little writers’ group, where about six of us come together every two weeks and each read something we’ve written, then give each other our thoughts, and let the writer (the one who just read their work out loud) ask their pressing questions: Do you think that first line is weird? Do you think this fits with the rest of my book? Is this part boring? It sounded boring when I read it. . .

We were in Margaux’s studio, and the five of us had finished our two-hour session, and had adjourned. Another artist, Jubal Brown, who is also working on a novel, was there. He walked around her studio, asking wryly, sarcastically, So is this where the magic happens? Margaux was finishing a suite of paintings for a show, and he stopped in front of one of my favorites, a huge canvas of leaves on trees, and branches, mostly green, but with a bit of brown, and little spots of pink peeking through.

He asked Margaux if it was unfinished. I grew tense, knowing it was done. No, she said, it’s finished. He said he didn’t like it. Too pretty. Too commercial. Then we all went outside her studio, and smoked. After Jubal left, Margaux said, I found that so relaxing—I love it when people say what they think. She didn’t mind that Jubal didn’t like it. After all, a dozen people have been invited to visit her studio in the past month: he didn’t like it, and neither did a certain curator, but other people did, and Margaux had her own opinion, which was her inner estimation of her work, laced with the ways that others have seen it.

Margaux and Jubal both know this sort of honesty is so important, and is evidence of a kind of love and care. He didn’t dislike the painting the way someone who doesn’t care about paintings can dislike a painting, in a way that makes an artist fume, in the way that I can fume with rage when I read something by someone online who didn’t like my book, because I feel they haven’t read the book fairly and I can’t be sure if they ever read books with the sort of openness with which I think books should be read. But I have never been angry at someone I care about, if they hate something I’ve written.

This happened last October: I showed someone I love a draft of my novel, and he said, Did you just throw all the pages in the air and however they fell down, that was the order you put them in? Of course I cried. I felt complete despair for two days, and I couldn’t return to my book for two months. I’m sure I had only shown it to him so that he would say, It’s great, and I could stop working on it—because even those of us who love writing are lazy and want to be done.

But the book was not finished. He saw it. I wanted him not to see it, but he did. And maybe I actually wanted him to see it, and to tell me the truth. After all, we don’t only send our books out; we send them out to specific people. If I want someone to love it, I know whom to send it to. If I need someone to read it who I know won’t love it, that’s a different person.

The author is speaking, before anyone else, to the friends to whom they send their books—and the friends speak back.

Finally I was able to work on it again, and I was able to make it better, and I would not have been served by him pretending he liked it. The kind of criticism that hurts us—from the people whose opinion we solicit—is the kind of criticism we want, even if it’s hard to take. And it feels so different from the barbs of the critic, who criticizes a book because it doesn’t please them. The criticism of the friend who is reading a draft is the criticism of someone who wants you to live up to your own standards, not theirs, and their critique doesn’t feel gratuitous, for the book can still be changed.

It’s not like kicking a corpse. Rather, it’s an attempt to help rouse to life something the artist hasn’t been able to make live. These early readers are not critics, they’re doctors. You can’t be angry at a doctor who says, The patient is barely breathing. The doctor wants the patient to breathe, while the critic doesn’t care. The doctor is speaking to the author, while the critic is not—and rightly so, they shouldn’t be.

But nor is the author speaking to them. The author is speaking, before anyone else, to the friends to whom they send their books—and the friends speak back, trying to help the author conjure the book. They all collectively care about some-thing in the middle, and often that’s what artist-friendships are all about: some mutual thing between them—literature, painting—and helping it grow. Virginia Woolf had people who functioned this way for her, too. I have never met a writer or an artist who doesn’t.

Art is made in the space between the artist and their early, chosen readers, a space that is filled with love, and with the pleasure of mutually solving a puzzle with care, and the understanding that while one person helps the other one now, the other will be helped out one day. This is an economy where no money flows, just the collective concern of people who care about a shared craft.

These are the readers the world never talks about, but who are, to me, the most important ones. I never feel more important when I am reading a book than when I am reading a friend’s draft, and it’s a deep pleasure to think that my reading will change a book, not only that a book will change me.

__________________________________

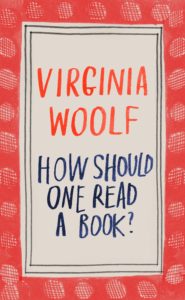

Excerpted from How Should One Read a Book? by Virginia Woolf, Introduction by Sheila Heti. Copyright © 2020 by Sheila Heti. Excerpted by permission of Laurence King Publishing Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.